Following the loss of the empire in 1857, even though nominally ruled by the emperor, the Muslims of India were in a state of depression and despondency. Clinging hopelessly to the past the Muslims looked for an anchor to give them security in the wake of oncoming Westminster style democracy, which for them meant change of one raj for the other. The Indian National Congress (INC) that came to be dominated by the majority Hindu community in India, sensing majority rule vigorously pursued the one man one vote system.

Given the strength of the Muslim Community, the 1909 Indian Councils Act, commonly known as Morley-Minto Reforms, allowed separate electorates for the Muslims, which became their armour to protect their interests. The INC disapproved separate electorates on the basis of religion. The issue remained central to Indian politics leading to independence.

Unity of India has remained a mirage during much of India’s history. The subcontinent became one geographic entity only with the advent of the British Empire. With more than 400 nominally independent princely states who could declare sovereignty in 1947, the British only provided a thin veneer of political unity. India’s diversity is therefore, reflective of many countries big or small within the boundaries of the subcontinent.

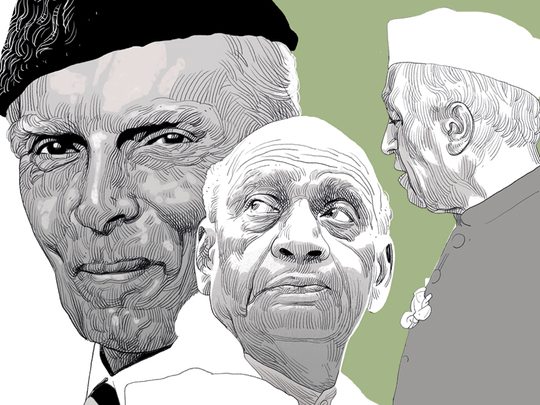

Credit for Indian unity following independence goes to Sardar Vallabhai Patel, India’s Bismarck and Deputy Prime Minister. His group wanted full powers and quickly. That “Congress desired partition” if its terms of a strong Centre were not accepted were laid out by Sardar Patel as early as April 25, 1947 in a meeting with Lord Mountbatten.

Mohammad Ali Jinnah, “the ambassador of Hindu-Muslim unity” had already established himself as a pan-Indian leader at the age of 39, when Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi arrived in India in 1915. An ardent believer of providing constitutional protection to the Muslims he was the main architect of the Congress — Muslim League (AIML) agreement commonly known as the Lucknow Pact in 1916.

The Pact conceded separate electorates, provincial autonomy and other safeguards for the Muslim community. Agreed solution to the major constitutional question for the two main communities was the big merit of this Pact. The extremists within the INC hit back and a committee (1928) headed by Motilal Nehru, with his son Jawaharlal as secretary, rejected ‘separate electorates’ and residual powers for the Centre, seeking instead a more powerful federal structure.

By adopting strictly Hindu cultural norms in administration and education the Congress ministries formed after the 1937 elections gave a taste to the Muslims of what was to follow once India was independent under a Westminster type democracy.

Concept remained vague

The concept of Pakistan both for its physical shape and its ideology remained vague leading different people to draw their own meanings.

Jinnah first laid out what he had in mind during his first meeting with the Cabinet Mission, asking the British government to ‘make an award … accepting the principle of Pakistan.’ Once this was done he saw no difficulty, says Ayesha Jalal, a leading writer, in getting the new states to agree to making a treaty to assure that matters such as defence, foreign affairs and communications are dealt by the Centre. In June 1946 Jinnah accepted Cabinet Mission Plan, preamble of which rejected Pakistan and allowed for grouping of Muslim majority provinces with maximum devolution of powers within a united India. This is enough of a testimony that the demand for Pakistan was initially more for recognition of ‘Muslim nationhood’ instead of a ‘statehood.’ It was only when Nehru ‘felt free to change or modify the Cabinet Mission Plan as it [INC] thought best’ opening the dreadful possibility of INC rolling out a constitution through its majority, Nehru laid a death knell to the Indian unity. The Congress again proved that it was not prepared to allay the fears of the Muslim community that constituted at least a quarter of Indian population.

Constitutional dispensation

Except for the Lucknow Pact 1916, the Congress strategy revolved around opposing any attempt conceding separate electorate for the Muslims and continued to stall Jinnah’s quest to seek a constitutional dispensation securing Muslim rights in India. If a weak Centre and provincial autonomy was the price to keep India united, Congress vehemently opposed it leading to not only the partition of India but also that of Punjab and Bengal.

Yasmin Khan, another noted scholar, suggests in The Great Partition that Lord Mountbatten, within a month of arrival in India was starting to think that Pakistan was inevitable and that he had arrived too late to alter the course of events fundamentally.

That Mountbatten, in complete disregard to the enormity of the task, decided to fast forward the British departure from June 1948 to August 15, 1947, giving just about 10 weeks for the division of the country and its assets will remain a riddle of history. ‘The fact that power was transferred to the two governments, neither of which knew the exact geographical boundaries of their respective states, adds another curious twist to Mountbatten’s handling of the partition of India.’ (The Sole Spokesman, p. 293). His interest was to let India burn while saving British lives.

What if the Congress had accepted a slightly weak Centre and provincial autonomy as a price to keep India united — will remain an unanswered question of history.

Sajjad Ashraf is an adjunct professor at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore. He was a member of Pakistan Foreign Service from 1973 to 2008 and served as Pakistan’s consul general in Dubai during the mid 1990s.

This is the second and last part of the series on India’s partition.