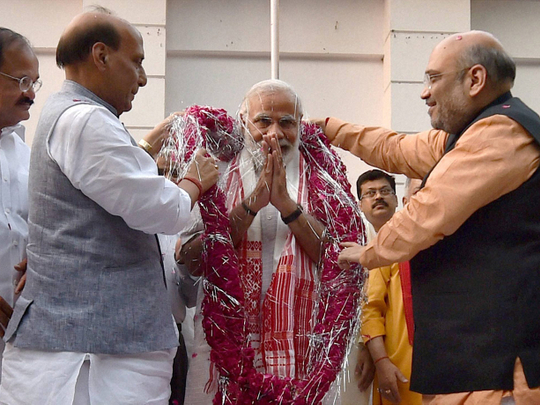

“From Kutch to Kamakhya. From Kanyakumari to Kashmir…” These were the words used by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) president, Amit Shah, to describe the spread of India’s ruling party’s footprints across the country.

With the BJP posting its maiden victory in the state elections in Assam making some inroads in West Bengal and Kerala, winning three and one seat, respectively, in the two states, Shah’s comment is not without merit.

After two humiliating defeats in Delhi and Bihar, the BJP winning Assam and picking up seats in West Bengal and Kerala is just the kind of fillip the party needed before getting into the business end of next year’s crucial assembly polls in Uttar Pradesh — the nerve-centre of the Hindi heartland and India’s most populous state.

The results from Assam, Bengal and Kerala are quite significant because these are states where the BJP has traditionally had a very marginal presence. In terms of organisational strength and mass base, eastern, southern and northeastern India have always ignored the saffron agenda and given short-shrift to the Hindu nationalist party, thereby forcing the BJP to be typecast as a party with a presence primarily in northern India, with some significant pockets of influence in the central and western parts of the country. In that sense, the BJP wresting power in Assam and bagging a little over 10 per cent of the vote share in states such as Kerala and Bengal is truly remarkable.

The winds of change started blowing during the 2014 general elections when the BJP won seven out of the 14 parliamentary seats in Assam and garnered an impressive 17 per cent vote-share in Bengal. That was the first indication of the party gaining a pan-India acceptance. But even in the midst of a popular wave in favour of Narendra Modi in 2014, very few political pundits would have put their money behind the BJP actually winning Assam or picking up a couple of seats in Kerala and Bengal.

In that sense, the recent assembly election results are no less significant than the general elections of 1989 when the BJP won 89 seats in the Lower House of parliament — a phenomenal rise from just two seats won in 1984. If 1989 saw the BJP gaining acceptance as a national outfit for the first time, then 2016 is definitely an indicator of the party raising its stakes well and truly beyond its traditional support base in northern, central and western India.

Before the 2014 general elections, the BJP top brass issued a clarion-call of establishing a “Congress-mukt Bharat” (Congress-free India). After the 2016 assembly election results, notwithstanding the debatable nature of such gimmicky coinage, the party seems to have taken some definitive strides towards achieving its goal of a “Congress-mukt Bharat”. Statistics show that after the latest assembly poll results, 69 per cent of India’s territorial space is now controlled by the BJP or one or more of its partners in the National Democratic Alliance.

Opening a huge void

In a multi-party democracy such as India, the decimation of the 131-year-old Congress party at the national and regional levels throws open a huge void in terms of political space. A rudderless central leadership that is out of touch with the party’s grass roots, a coterie of sycophants that shies away from calling a spade a spade, a corruption-tainted lacklustre run of 10 years in government at the Centre — from 2004-2014, and a blind subservience to ideological orthodoxy steeped in a hackneyed concept of socialism have all contributed to a growing political abscess within the Congress.

While regional parties have benefited from Congress’s fast-receding influence in the states for some decades now, at the national level, it is the BJP that stands to gain from the political vacuum created by the self-induced comatose state of India’s grand old party. And this presents the BJP with both an opportunity as well as a challenge.

It’s a windfall for the Modi brigade in the sense that the Congress’s decline is almost relentless and as long as the party does not show enough confidence to free itself from the strappings of the Gandhi family name and embark on a major course correction, the BJP will only keep gaining more political capital.

With the UP state elections slated for next year and until the next general elections in 2019, the BJP will have substantial time and opportunity to try and occupy as much of the vacuum left behind by the Congress as possible.

Given its disciplined cadre base, the logistical support from the Rashtriya Swyamsevak Sangh, its dedicated band of patrons in corporate circles in India and abroad and the political clout wielded by the Modi-Shah duo, the BJP will continue to pose a serious threat to the Congress party’s survival strategies — if there are any, that is.

And therein lies the big challenge for the BJP. No matter how formidable the party looks right now, it has to keep the fringe where it belongs — the fringe. In the last two years since BJP stormed to power at the Centre, there has been an increasing attempt by the radical Right within the party fold to try and occupy centre stage by propagating an ideology of intolerance through a lexicon of hatred and exclusion that runs counter to India’s pluralistic and secular ethos.

The challenge for the BJP central leadership now is to keep these radical elements on a tight leash and thwart all possibilities of its development agenda being hijacked by a pseudo-nationalistic fervour.

Succumbing to temptation and complacency is the easiest thing. Resisting them is what will separate the men from the boys.

You can follow Sanjib Kumar Das on Twitter at www.twitter.com/@moumiayush