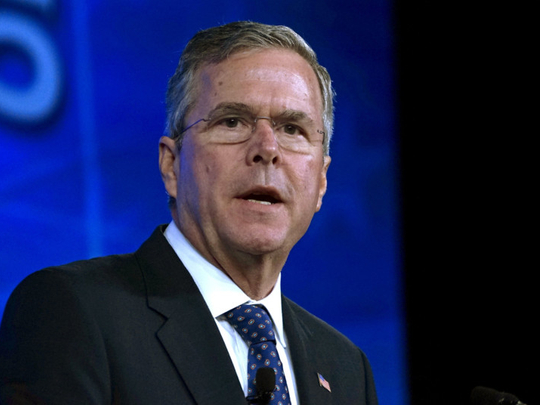

When Jeb Bush — the former governor of Florida, all-but-announced Republican presidential candidate and younger brother of George W. — stumbled badly earlier this month over seemingly simple questions about the 2003 US invasion of Iraq, his opponents were quick to pounce. Asked whether knowing what we know now the invasion still seemed like a good idea Jeb said “yes”.

Within days, virtually every other Republican presidential candidate or candidate-to-be (the field currently includes a number of people who, like Jeb himself, are presumed to be running but have not yet made it official) had loudly criticised Jeb. Jeb’s fumbling attempts to clarify his initial answer over the next few days only seemed to make matters worse.

Beyond his political opponents, however, Bush also found himself the target of criticism from the talk radio hosts who wield inordinate influence over America’s right-wing politics. “What he said was just rubbish,” Laura Ingraham told her listeners. “You can’t still think going into Iraq now, as a sane human being, was the right thing to do.”

The net result, according to Josh Marshall, editor of the left-leaning website ‘Talking Points Memo’ was a sudden and new consensus among Republicans “that the decision to invade Iraq was — at least in retrospect — a mistake”. Which is really pretty extraordinary. During the last presidential campaign, a willingness to defend the Iraq war was more or less part of the price of admission to Republican politics.

It is particularly instructive to compare this about face to the GOP view of the Vietnam War in the years following that conflict. Today, there is a general consensus in the US that the Vietnam War (a term that, in America, usually includes US involvement in Cambodia and Laos during the same era) was an ill-conceived mistake but also, perhaps, an inevitable one given the realities of the Cold War. A certain strain of American liberal continues to believe that had president John F. Kennedy lived, the war would never have been fought, and left and right alike tend to blame the whole thing, a little too conveniently, on Kennedy’s successor, Lyndon Johnson.

Vietnam tore apart late-1960s America, drove Johnson from office and put president Richard Nixon in the White House. The last American troops left the country in 1973, and the war itself ended in 1975, but it poisoned the country’s politics for decades. What one had done during the war became a litmus test for national office in both parties. President Bill Clinton’s opposition to the war as a student and his efforts to avoid being drafted into the military nearly sank his presidential campaign in 1992. Evidence that a young George W. Bush had loudly supported the war even as his family pulled strings behind the scenes to insure he would not have to fight it were a problem during his run for the White House in 2000. On the political right, in particular, any suggestion that the war was less than noble and morally upright was political suicide well into the early years of this century.

By contrast, with America barely three years out of Iraq (yes, there are still several thousand US troops there but, in the public mind at least, it is not the same thing) there suddenly seems to be near-universal agreement among politicians of both parties that the war there was a tragic, eminently avoidable, mistake.

If Iraq does not seem to be poisoning US politics the way Vietnam once did, it is probably still too soon to say what lessons the political and pundit classes have learned from the experience. Specifically, whether the new consensus surrounding the war reflects a broader change in attitudes towards military action in the Middle East. Among Republicans it appears to have injected a note of caution into the discussion. The GOP hopefuls are bellicose when the subject of Daesh (the self-proclaimed Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant) or Iran is raised, but most of them become studiedly vague when asked if their threatening language means they favour war. Hillary Clinton seems (not unwisely, politically speaking) to be trying to avoid the topic for as long as she possibly can.

Yet, the issue cannot be avoided forever. The issues facing America in the Middle East go beyond Iran’s nuclear programme, Daesh and a host of concerns from oil prices and GCC cooperation to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and the continuing legacy of the Arab Spring. New problems will surely make their way onto this list sooner or later. Disengaging from the region is not really an option; so the real question US presidential candidates ought to be answering is not whether they would have invaded Iraq a dozen years ago, but what lessons they have learned from these last dozen years.

Gordon Robison, a longtime Middle East journalist and US political analyst, teaches political science at the University of Vermont