‘A photograph, no matter how emotionally wrenching, can only do so much,” wrote Paul Slovic and Nicole Smith Dahmen in QZ.com.

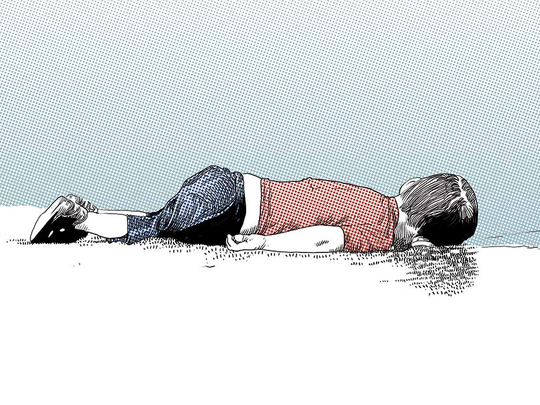

The photograph referred to in their comment was that of three-year-old Aylan Kurdi, whose body was washed ashore on some Turkish beach in September 2015.

It has been a year since that tragic photograph — of an innocent child, face-down and lifeless — haunted and captured the attention of the world, alerting the international community to the urgency of the horrific war in Syria.

Estimates vary, but it seems fairly certain that anywhere between 300,000 and 500,000 people have lost their lives in Syria’s ongoing war. Tens of thousands of those are children. The conflict in Syria is perhaps the most multifarious since the Second World War. There are too many parties and too many proxy wars happening all at once.

Despite the international discontent generated by Aylan’s photo, the image was disturbingly used by various parties to validate their reasons for war. In some way, the photo had itself become a weapon in the hands of the warring parties, as opposed to a rally cry for an urgent ceasefire and eventual peace.

This reaction was no different from the more recent release of a photo of a five-year-old boy, Omran Daqneesh. His little body was seated alone at the back of an ambulance after being dug out from underneath rubble — his tiny hands on his lap, his face dirty, bloodied and dazed. This pitiful image was barely used as an opportunity to make a strong case of why a ceasefire must be reached; why the war must end. It was nothing more than a lost opportunity to untie the world in its anger and horror against this war.

Instead, the picture found its way to the stifling media arguments made by those who continue to stoke the fire for yet more firepower and greater military interventions.

What has become of Syria and its people? This nation that was unparalleled in its beauty, history, poets and intellectuals (which, like Iraq, was equally destroyed) is now encapsulated in a mere photograph — of a dead child, or another dying — in photos that make the occasional buzz on social media circles, but eventually fade away.

Few are innocent in this attempt at fetishising Syria’s tragedy without having to contend with the roots of its conflict, or playing a constructive part in pressuring various governments to find a solution that would end the ugly war and spare the lives of children.

To a certain extent, we are all participants in the dehumanisation of Syria, sharing photos without context, appealing to random strangers to ‘do something’, and shedding social media tears with no plan in mind and no attempt at meaningful mobilisation, while taking sides in a conflict where all hands are drenched with blood.

A recent story conveyed to me by an Italian writer who recently visited Jordan with a small NGO, was particularly disturbing.

Her story was of a fellow Italian ‘activist’ who visited a Syrian refugee encampment in the Jordanian desert and was keen on creating the perfect emotional impact for her photos, to the extent that she did not mind setting up the refugees to pose in a degrading fashion.

The Italian ‘activist’ was insistent on a specific photo, as if her social media activism career was dependent on it. As if the misery of a poor Syrian child was not palpable enough in his dejected face and his rash-infested skin, she wanted to define a point of absolute misery for a perfect Instagram image. So she handed him a bucket filled with rocks collected from the arid Jordanian desert, not far away from the Syria border. He carried the heavy rocks and innocently posed.

The boy, along with his family, and many others lived in tents in the middle of nowhere. The refugee camp was deemed ‘informal’. It received no water or electricity and not even regular supplies of food, however meagre. The refugees subsisted on what drivers racing at ridiculous speed on a nearby highway would toss their way.

To keep the tents in their intended location, the refugees had positioned buckets filled with rocks atop the wooden poles, thus keeping the tattered tents in place, especially during the gusts of violent sandstorms.

The ‘activists’ took their fill of photos with no particular purpose, aside from exhibiting their peculiar brand of ‘solidarity’, which often finds its way to social media platforms, accompanied with seemingly fitting emoticons and generalised, empty truisms.

Expectedly, their social media friends validate the empty gestures by exalting the courage, heroism and greatness of the person who took the photo. In reality, however, the ‘activists’ have done nothing but aggrandised their false sense of valour, and injured the dignity of the proud refugees, while selling them plenty of false hope as they continue to await salvation in the desert.

The baffled Syrian boy, who must have participated in that charade in the hope of getting a sandwich or even a piece of chocolate, carried the bucket of rocks so that the Italian ‘activist’ would produce a photo that was the personification of despair. And it was picture-perfect, indeed, followed by a fun-filled trip to the Dead Sea and other Jordanian attractions.

Humanitarian crises

The scene in the Jordan refugee camp happened recently but is actually a recurring reality, where ‘activists’ — westerners, especially — seek in the Middle East (and all over the world) a respite from their consumerism-driven, often uneventful world.

They view their relationships with humanitarian crises as saviours, carrying the ‘White Man’s burden’ wherever they go, yet always aware, if not proud, of their privilege and their sense of superiority.

For many, conflicts like the one in Syria are too messy, too complicated, and ‘too political’. It is far easier to declare oneself an ‘activist’ and snap a thousand photos that parade victims of war in total isolation from one’s own moral responsibility.

Photographs like that of little Aylan, Omran and countless others should not be exploited as a further justification for war, but should become the impetus leading to an opportunity to galvanise enough rage to end the war.

Nor should images of dead, bloodied and hungry Syrian children be an opportunity to aggrandise the egos of attention-seeking ‘humanitarians’ and false ‘activists’.

Humanitarianism is not a photo op: It is not an adventure; it is not a vacation; it is not a stress or guilt-reliever; it should not be an expression of cultural hegemony or driven by a sense of superiority, and must refrain from selling false hope.

A true humanitarian activist is one who is able to make a tangible difference to the lives of others, someone who is focused, sensitive to cultural sensibilities, compelled by a tug of moral responsibility, able to read political contexts and daring enough to hold accountable those responsible for war and other collective tragedies.

Chances are the Syrian child with the bucket full of rocks had his photo exhibited to the delight of many other social media ‘activists’.

Yet chances are, he is still hungry and waiting.

Dr Ramzy Baroud is an internationally-syndicated columnist, media consultant and author of several books. His latest book is My Father Was a Freedom Fighter: Gaza’s Untold Story. Italian writer Romana Rubeo contributed to this article.