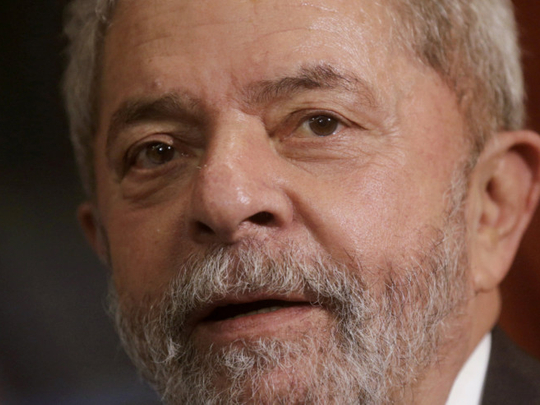

I didn’t watch Luiz Enacio Lula da Silva’s five-hour long questioning with the judge two weeks ago. A trial shouldn’t be a show, so I left that circus to the journalists. From what I’ve seen, it seems clear enough that the former Brazilian president is in a pickle. Instead of actually answering the magistrate’s questions, he merely said he didn’t know anything, even when presented with an incriminating document about the beach apartment he allegedly received as a bribe.

No, Lula brushed the whole thing off, saying that was all a part of his deceased wife Marisa’s business ...

And yet, most people actually think Lula did pretty well in court. He demonstrated all his cunning, positioned himself as the victim of a partisan judge and demonstrated that he still has what it takes to return to Brazil’s political ring before the presidential election in 2018.

Two games are being played at the same time. The first one is legal, played along clear and well-defined boundaries (or so we hope). In this game, Lula is unquestionably being beaten. Nothing he told the judge neither altered the might of the evidence against him nor cleared his name in this strange penthouse apartment affair.

Clearly, Lula’s business isn’t money but power. Of course, it doesn’t mean he can’t take some economic advantage here or there. But as it happens, he was earning $200,000 (Dh735,600) per appearance on the global lecture circuit. Why would he then accept an apartment illicitly if he would have been able to purchase it without making much of a dent in his accounts? Only a profound indifference towards legality, the feeling that he was genuinely above the law, would explain this. That Lula could have indulged in thinking he was all-powerful is hardly outside the realm of the possible.

The other game, of course, is the political one. Here, there are no permanent rules. Anything that works, that sticks, anything to help conquer power, is acceptable. Lula is a Brazilian master of this game; and he’s confident that, if he manages to enter the presidential race next year, he will avoid jail and win a remarkable return to the office he had held from 2003-2011. He also demonstrates he’s learned his lesson from his two previous mandates: He will do anything to annihilate any threat to his position, starting with freedom of the press.

Such polarisation turns out to fit him like a glove. The last thing he wants is to be seen for what he actually is: A normal, common defendant under investigation for potentially criminal behaviour. The more his trials are perceived as political war, facing crusading Justice Sergio Moro, the more Lula will benefit from the situation. This isn’t a trial, it’s a fight. Lula isn’t a defendant, he’s a warrior — and we will eventually have to pick one side.

The high point of this strategy will be entering the race for the 2018 presidential election. Once his name is among the list of candidates, the game changes. No legal decision will be able to stand in his way given the direct political impact.

Al Capone got caught for tax evasion. Lula can fall because of the apartment, or any of the accusations thrown at him. But will the wheels of justice spin quickly enough? If not (and lawyers are there to make sure of that), imagine the beautiful future taking shape: Lula, found guilty in the first instance but quick to appeal to a higher court, enters the presidential race; the most ferocious campaign in the history of Brazil ensues; he wins.

At this point, the political game would certainly prevail over the legal one. The judiciary will find itself faced with a dilemma: It could sentence the elected president, but declaring his candidacy invalid would be an incendiary decision that could well spark open violence on the streets; or it could look the other way and submit to executive privilege, making the president officially above the law.

In either case, the beach apartment wouldn’t be remembered as a careless lapse into hubris, but as the omen of his veritable omnipotence. Measured in dramatic terms, Brazilian justice and politics will continue to beat the best of Netflix.

— Worldcrunch — in partnership with Folha de S. Paulo/New York Times News Service

Joel Pinheiro Da Fonseca is a Brazilian economist.