The 2017 UN climate change summit enters its important, final week on Monday. Coming amidst growing scientific alarm about global warming, the chair of the event has called for a “visionary” summit that “restates the vision of the Paris” landmark climate accord agreed in 2015.

It is fitting that the Fiji prime minister is chairing the meeting given that the very existence of low lying islands is threatened by sea level rises due to climate change, redrawing the map of the world with key cities like Rio de Janeiro, Shanghai, Osaka, Miami, Alexandria and The Hague threatened too. On October 30, the World Meteorological Organisation warned the last time carbon dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere were as high as now was three to five million years ago, and that temperatures could continue to spike, hitting dangerous levels by 2100 -- unless world leaders take major action.

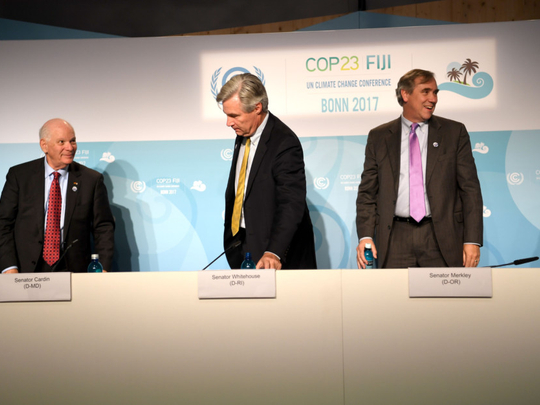

In what is a tough backdrop for the first Pacific island nation to chair the event — the first time the annual summit has convened since President Donald Trump pulled the US out of the Paris deal — moving forward with implementation of Paris is a major point of discussion. This includes delivering on the targets that were decided by each country referred to as the nationally determined contributions (NDCs).

One of the highlights of last November’s conference, held in Morocco, was presentation by individual countries of their plans to achieve these NDCs. This reflects the fact that Paris is a flexible, ‘bottom-up’ approach whereby countries develop bespoke plans to realise emissions targets with national and sub-national governments working in partnership with business.

In other words, while Paris created a global architecture for tackling global warming, it recognises that diverse, often decentralised policies will be required by different types of economies to meet climate commitments. While the wisdom of this may appear obvious, it represents a breakthrough from the more rigid ‘top-down’ Kyoto Protocol framework.

Kyoto worked in 1997 for the 37 developed countries and the EU states who agreed it. But a different way of working is needed for the more complex Paris deal which involves more than 170 diverse developing and developed states which agreed to reduce global carbon dioxide emissions by 80% by 2050.

That this approach makes good sense is reflected in the diversity of climate measures that countries, pre-Paris, had started to make in response to global warming. This has been illustrated in reports by the Grantham Institute at the London School of Economics, including in 2015, which focused on 98 countries plus the EU, together accounting for 93 per cent of global greenhouse gas emissions, and revealed there are more than 800 climate-change laws and policies in place across the world, rising from 54 in 1997.

Approximately half of these (398) were legislative measures, and half (408) executive actions (e.g. decrees). And 46 new laws and policies were passed in the 12 months prior to the 2015 Paris summit alone — highlighting that domestic measures to address global warming are being approved at a strong clip.

Some 45 countries, including the 28 EU members as a bloc, have economy wide targets to reduce their emissions. Together, they account for over 75 per cent of global emissions.

In addition, 41 states have economy-wide targets up to 2020, and 22 have targets beyond 2020. Moreover, 86 countries have specific targets for renewable energy, energy demand, transportation or land-use, land-use change and forestry, while some 80 per cent of countries have renewable targets; the majority of them are executive policies.

This underlines that the best way to tackle climate change, going forward, is a decentralised approach with nations meeting their target commitments in innovative and effective ways that builds on this momentum. Take the example of Morocco, the host of last November’s summit, which has become a leader in renewables.

The country gets nearly 30 per cent of its energy from renewable energy and is aiming for a goal of 50 per cent by 2030. It is an agenda setter on renewables for other emerging economies, including in North Africa, and one of the highlights of that summit was a pledge by almost 50 emerging markets from Africa to the Americas to try to become zero carbon societies by 2050 driven by these ‘new’ energies.

A key part of the drive here is harnessing how renewables could drive a remarkable new industrial revolution potentially becoming a key source of economic growth and sustainable development. In Morocco, the drive toward renewables relies not just on big infrastructure projects like solar and wind plants, but also less expensive local, small-scale initiatives to encourage key eco-friendly projects including in agriculture.

Thus as well as major power projects, such as the Energipro initiative which has provided Africa’s largest wind farm, and what will become the largest concentrated solar power plant in the world at Ouarzazate, there is emphasis on encouraging the agricultural sector (which employs more than 40 per cent of the workforce) to become more climate-conscious. There are big plans underway, for instance, with irrigation systems to reduce use of water and energy.

Morocco’s moves here are underpinned, in part, through international collaboration which highlights that another key strength of Paris’s emphasis on decentralised solutions is the international partnerships spawning between regions, cities and institutions right across the world. For instance, the University of Hull in England has forged a relationship with the International University of Agadir, Universiapolis, to share climate research insights and technological solutions to help realise Morocco’s goals to promote lower carbon growth.

Taken overall, implementing Paris will require diverse, often decentralised policies by different types of economies. If countries now leverage the flexibility of the framework, it can become a key foundation stone of future sustainable development for billions across the world in the 2020s and potentially beyond.

Lord Prescott is former UK deputy prime minister and was Europe’s chief negotiator for the Kyoto Protocol. Andrew Hammond is an associate at LSE IDEAS at the London School of Economics.