Clutching on to that coveted gold statuette, lying in his hospital bed in Kolkata, acclaimed Indian filmmaker Satyajit Ray was effusive in his praise of Hollywood. It was early 1992, just 24 days before Ray breathed his last. On that memorable evening, the giant screen at Dorothy Chandler Pavilion in Los Angeles flashed a video footage of Ray accepting an honorary Oscar for a life dedicated to the art and craft of soul-stirring cinema. As Audrey Hepburn did the honours on stage, a rapturous applause greeted the announcement of Ray’s name at the 64th Academy Awards. “Everything that I have learnt about the craft of cinema is from the making of American films. I have been watching American films very carefully over the years. I loved them for the way they entertained and later loved them for what they taught,” Ray said in his acceptance speech, underscoring the significance of Hollywood in a career spanning four decades.

What Ray said about the world’s most famous and celebrated film industry is something that millions around the world will very fondly acknowledge.

Indeed, right from the silent era, when D.W. Griffith’s In Old California (1910) was presented to the world, and until this summer’s inarguably best offering in the form of Christopher Nolan’s Second World War classic Dunkirk, Hollywood has mesmerised, influenced, structured and populated a movie lovers’ world of a celluloid rendition of art imitating life in the best way it can.

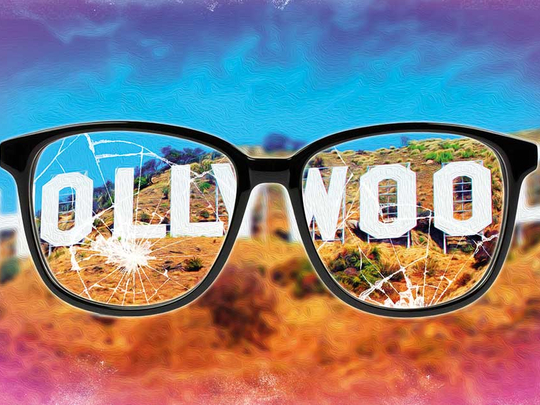

However, it probably saddens a cinema lover to no end, and this need not be culture specific, to see that even after 107 years of being a glorious repository of the moving art-form, Hollywood’s embrace of the world is at best partial and at worst prejudiced and even bigoted at times. The shocking absence of even one Asian or African face in Dunkirk is the latest and one of the surest signs of cultural authoritarianism, myopic delineation of historical truth and a snooty disapproval of all that constitutes “popular culture” in other parts of the globe.

Nolan’s cinematographic astuteness leaves you in trance, its aural effects blending seamlessly with the canvas to produce an ambience that completely compensates for paucity of dialogues. Intellectually too, Nolan’s offering is five-star review material — in the same league as his earlier masterpiece Inception.

And yet, as one steps out of the 70mm realm of Dunkirk, one is struck by a nagging feeling of injustice — so much so that even generous granting of a ‘poetic licence’ to Nolan does not offer sufficient redemption. In ignoring the fact that along with those 400,000-odd Allied soldiers stuck on Dunkirk beach, there was a sizeable number of Indian soldiers who were part of the British colonial forces — paying the price of 20th-century geopolitics as much as their British and French colleagues — Nolan has laid bare an obscurantism that has bedevilled the West in general and Hollywood in particular for more than a century since In Old California hit the screens: That the East in general, and India in particular, is dispensable when it comes to staying committed to historicity and cultural and artistic altruism. Dunkirk is a reaffirmation of the same mindset that has characterised the West’s conceptual-construct of India and the Orient as all things bizarre and fantastical, that can constitute the kernel of a phantasmagoria such as Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, but can never offer the intellectual template or the cultural cornucopia that comes so aesthetically loaded with a Roman Holiday or a Gone With the Wind.

Easy picking

As a counter-argument, one may cite Lawrence of Arabia or Gandhi as examples of Hollywood looking East for an enriching cinematic experience. But the point is, such instances are so few and far between that it only reminds one of the adage: Exception that proves the rule. Moreover, the justice meted out by a Gandhi is negated many times over by the depiction of something as obnoxious as gorging on chilled monkey brains (Indiana Jones ...) and some such grotesque depiction of India. The Orient is always easy picking when it comes to taking such unmoored liberties with the western audience’s intellectual fecundity.

For arguments’ sake, it can also be pointed out that the onus to nominate good cinema — for it to be showcased in Hollywood — lies with the country of origin. Point granted. But just factor this in: One of the many parameters for a film to be nominated in an Oscar category, is its screening for paid admission in Los Angeles. Charlie Chaplin’s Limelight, produced in 1952, had to wait until 1972 to win an Oscar — only after it played to the public in Los Angeles. And that too for a film that was entirely filmed in Hollywood. One can easily guess the fate of films that are shot and produced oceans away from America. If the moon isn’t shining on my balcony, there’s no moon tonight!

The irony is that this rather constricted worldview of Hollywood has sometimes seen due accolades being denied to some of America’s own luminaries such as Marilyn Monroe, Stanley Kubrick, Mia Farrow, Robert Altman, Judy Garland to name just a handful. Collateral damage?

Now let’s look at the flip side. In recent years, several popular mainstream actors from the Hindi film industry — Priyanka Chopra and Deepika Padukone being the foremost among them — have earned headlines in India and beyond with their Hollywood ventures such as XXX (featuring Padukone) and Baywatch (featuring Chopra). Such a buzz may give one the impression that indeed Bollywood is, at long last, making waves in Hollywood.

So what’s the issue?

The point is that one should not be blindsided by euphoria over what is at best Hollywood’s glorified and cleverly-packaged presentation of kitsch. It is indeed phenomenal how, along with its classics and numerous timeless offerings of good cinema, Sunset Boulevard productions have so successfully managed to make good business out of presenting mediocrity in the garb of pop-culture. Given a market of the size of India — its 1.3 billion-strong consumer base, a flourishing middle class and with 65 per cent of its population below the age of 35 — it makes common business sense to cash in on ‘instant Karma’ (not of the John Lennon variety, though), just like the way American fast-food chains have got a post-liberalisation urban India smacking its lips over burger-fries. And what better way to do that than have popular faces from India’s mainstream cinema sell the Hollywood hologram to the target audience in the world’s largest film-producing country (1,602 films produced in India in 2012, compared to Hollywood’s 476). Paramount Pictures, Universal Studios and the likes have all been involved in producing commercial films in India in the last five years or so because all these production houses see India as a happy hunting ground, where kitsch can be made — and marketed. An XXX or a Baywatch or for that matter even a television series such as Quantico (featuring Chopra) does find fair bit of traction with Indian audiences. And mind you, this is by no means meant to be an affront to those Indian actors who have carved out their own little niche in Hollywood. What they have achieved is indeed commendable. Yet, it will be interesting to see if a Sholay or a Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge ever constitutes even a footnote in the world’s most venerated entertainment industry’s annals.

And this is where the problem lies. Exporting kitsch as pop-culture is Hollywood’s second nature, or so it seems. But accepting kitsch packaged as pop-culture from any other part of the world is sacrilege!

The hypocrisy has been laid bare by Dunkirk. Nolan knew that to render cinematic brilliance to a Second World War true story, historicity, to the extent of its Oriental link, could be dispensed with. But Paramount Pictures, producers of Baywatch, could take no such liberty. They knew that to rake in the moolah from an industry with an annual turnover of $2.28 billion (Dh8.38 billion), a lip-glossed Priyanka Chopra’s presence on the posters and promos were as important as a muscle-flexing Dwayne Johnson!

‘That is fantastic’

In a signed article in the Statesman newspaper on August 14, 1949, Ray wrote, quoting French director Jean Renoir: “‘Look at the flowers,’ said Renoir one day while on a search for suitable locales in a suburb of Calcutta [Kolkata] for his film The River. ‘Look at the flowers. They are very beautiful. But you get flowers in America too. Poinsettias? They grow wild in California, in my own garden. But look at the clump of bananas and the green pond at its foot. You don’t get that in California. That is Bengal and that is fantastic.’”

Indian filmmakers such as Ray, Rituparno Ghosh, Adoor Gopalakrishnan, Shyam Benegal, Ritwik Ghatak — to name only a few — have produced cerebral cinema for decades. Yet, Hollywood has been rather economical in its enthusiasm to embrace such a rich and varied mosaic. And that probably holds true for many other regions and cultures churning out good cinema year on year, around the world. The honorary Oscar to Ray came when he was on his death bed, literally, as it took the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences 37 long years to realise Ray’s true worth as a filmmaker. And even then, his epochal Pather Panchali (Ballad of the Road) or Gopalakrishnan’s Swyamvaram (One’s Own Choice) or Ghosh’s Chokher Bali (The Constant Irritant) ... will scarcely ever find a mention in the haloed portals of Dolby Theatre (home to the Oscar nights). And the ultimate loser for such myopia is world cinema.

Any takers for an Amitabh Bachchan-Rekha Hindi remake of The Bridges of Madison County, on a prominent Hollywood banner?

Oh yes!

A lifetime achievement Oscar for Bachchan?

Oh no!

At the Oscar night in 1992, as Audrey Hepburn pronounced Satyajit Ray’s surname as “Raaye” — just as one would in Bangla — one felt it was perhaps one of the surest signs of cultural outreach to a world audience. Quarter of a century later, that pronunciation bit stands as nothing more than a Hollywood tokenism in lexicology. Sad, but true.

You can follow Sanjib Kumar Das on Twitter at www.twitter.com/@moumiayush.