The image we often conjure of Africa is of seemingly endless, protracted and bloody conflicts. But western media, which plays a leading role in presenting Africa often in a negative light, rarely addresses Africa’s conflicts and civil wars in the context of western culpabilities.

The Uppsala Conflict Data Programme reported on the involvement of 12 African countries in major armed conflicts in 2014. The following year, the number increased to 15.

Yet, more conflicts are on the horizon considering the ‘water war’ now brewing in the Horn of Africa. If a resolution is not found soon, several African countries could find themselves fighting a bitter war.

Writing in Salon.com under the title “Is War about to Break out in the Horn of Africa? Will the West even Notice?” Steven A. Cook calls for “American mediation”, blaming US President Donald Trump’s administration for not making the Horn of Africa a top foreign policy priority, thus leaving Vladimir Putin’s Russia to fill the gap of American absence. But a bird’s-eye view of US interventions in Africa would illuminate two facts: first, the US is already too involved in Africa, and, second, US involvements often stir up, not mediate the end of conflicts.

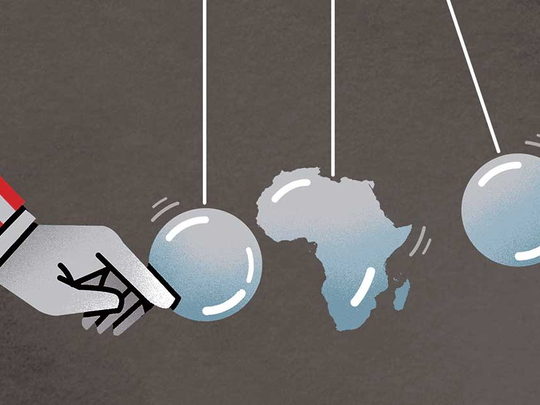

Indeed, there is a real — but largely concealed — war taking place throughout the African continent, involving the United States, an invigorated Russia and a rising China. The outcome of the war is likely to define the future of the continent as well as its global outlook.

The problem predates the Trump presidency by nearly a decade.

In 2007, under the pretext of the ‘war on terror’, the US consolidated its various military operations in Africa to establish the United States Africa Command (AFRICOM). With a starting budget of half a billion dollars, AFRICOM was supposedly launched to engage with African countries in terms of diplomacy and aid. But, over the course of the last 10 years, AFRICOM has been transformed into a central command for military incursions and interventions.

However, that violent role has rapidly worsened during the first year of Trump’s term in office. Indeed, there is a hidden US war in Africa, and it is fought in the name of ‘counter-terrorism’.

According to a VICE News special investigation, US troops are now conducting 3,500 exercises and military engagements throughout Africa per year, an average of 10 per day. US mainstream media rarely discusses this ongoing war, thus according the military ample space to destabilise any of the continent’s 54 countries as it pleases.

“Today’s figure of 3,500 marks an astounding 1,900 per cent increase since the command was activated less than a decade ago, and suggests a major expansion of US military activities on the African continent,” VICE reported.

Following the death of four US Special Forces soldiers in Niger on October 4, US Secretary of Defence James Mattis made an ominous declaration to a Senate committee: these numbers are likely to increase as the US is expanding its military activities in Africa.

Mattis, like other defence officials in the previous two administrations, justifies the US military transgressions as part of ongoing ‘counter-terrorism’ efforts. But such coded reference has served as a pretence for the US to intervene in, and exploit, a massive region with great economic potential.

The old colonial ‘Scramble for Africa’ is being reinvented by global powers that fully fathom the extent of the untapped economic largesse of the continent. While China, India and Russia are each developing a unique approach to wooing Africa, the US is invested mostly in the military option, which promises to inflict untold harm and destabilise many nations.

The 2012 coup in Mali, carried out by a US-trained army captain, Amadou Haya Sanogo, is only one such example.

In a 2013 speech, then US secretary of state Hillary Clinton cautioned against a “new colonialism in Africa (in which it is) easy to come in, take out natural resources, pay off leaders and leave.” While Clinton is, of course, correct, she was disingenuously referring to China, not her own country.

China’s increasing influence in Africa is obvious, and Beijing’s practices can be unfair. However, China’s policy towards Africa is far more civil and trade-focused than the military-centred US approach.

The growth in the China-Africa trade figures is, as per a UN News report in 2013, happening at a truly “breathtaking pace”, as they jumped from around $10.5 billion per year in 2000 to $166 billion in 2011. Since then, it has continued at the same impressive pace.

It should come as no surprise then that China surpassed the US as Africa’s largest trading partner in 2009.

The real colonialism, which Clinton referred to in her speech, is, however, underway in the US’s own perception and behaviour towards Africa. This is not a hyperbole but in fact, a statement that echoes the words of President Trump himself.

During a lunch with nine African leaders at the UN last September, Trump spoke with the kind of mindset that inspired western leaders’ colonial approach to Africa for centuries.

Soon after he invented the non-existent country of ‘Nambia’, Trump boasted of his “many friends (who are) going to your (African) countries trying to get rich.”

“I congratulate you,” he said, “they are spending a lot of money.”

The following month, Trump added Chad, his country’s devoted ‘counter-terrorism’ partner, to the list of countries whose citizens are banned from entering the US.

Keeping in mind that Africa has 22 Muslim majority countries, the US government is divesting from any long-term diplomatic vision in Africa and is instead, increasingly thrusting further into the military path.

The US military push does not seem to be part of a comprehensive policy approach either. It is as alarming as it is erratic, reflecting the US constant over-reliance on military solutions to all sorts of problems, including trade and political rivalries.

Compare this to Russia’s strategic approach to Africa. Reigniting old camaraderie with the continent, Russia is following China’s strategy of engagement (or in this case, re-engagement) through development and favourable trade terms.

But, unlike China, Russia has a wide-ranging agenda that includes arms exports, which are replacing US weaponry in various parts of the continent. For Moscow, Africa also has untapped and tremendous potential as a political partner that can bolster Russia’s standing at the UN.

Aware of the evident global competition, some African leaders are now labouring to find new allies outside the traditional western framework, which has controlled much of Africa since the end of traditional colonialism decades ago.

A stark example was the late November visit by Sudan’s President Omar Al Bashir to Russia and his high-level meeting with President Vladimir Putin. “We have been dreaming about this visit for a long time,” Al Bashir told Putin, and “we are in need of protection from the aggressive acts of the United States.”

Wary of Russia’s Africa outreach, the US is fighting back with a military stratagem and little diplomacy. The ongoing US mini wars on the continent will push the continent further into the abyss of violence and corruption, which may suit Washington well, but which will bring about untold misery to millions of people.

It goes without saying that Africa is better off with less American interventions, even those sold under the brand of political ‘mediation.’

Ramzy Baroud is a journalist, author and editor of Palestine Chronicle. His forthcoming book is The Last Earth: A Palestinian Story (Pluto Press, London).