In April 2011, former British prime minister David Cameron made a very surprising statement for an English politician, during his visit to Pakistan, when he said: “Britain was to blame for decades of tension and several wars over the disputed territory [Kashmir], as well as other global conflicts.”

On his visit to India in February 2013, Cameron visited Amritsar in the state of Punjab and placed a wreath on a memorial for victims of the Jallianwalah Bagh massacre committed by the British army in 1919 and wrote in the guest book that the massacre was “shameful”. But he did not apologise for this massacre, which Mahatma Gandhi described at the time that it “rocked the pillars of the empire”.

In fact, Cameron’s statement needs a slight addition. Britain is responsible for nearly 96 conflicts around the world, some of them considered the worst and bloodiest.

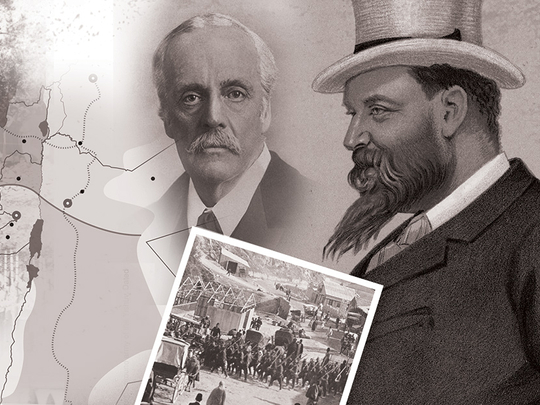

SPECIAL COVERAGE ON BALFOUR DECLARATION:

Ramzy Baroud writes: How Britain became an obstacle to peace

Fawaz Turki writes: Dear Mr Balfour, your Zionist wrongs will be corrected

Jumana Al Tamimi writes: 67 words that changed course of Arab history

Mahmoud Abbas writes: Why Britain must say sorry for a century of injustice

Diana Buttu writes: We live a life of fear in an open-air prison

Fadi Esber writes: How Truman paved the way for Jewish occupation

Cameron’s statement did not pass unnoticed by the British political elite. Some reactions to what they considered an “apology” for the British colonial past were as “a mistake” according to Daisy Cooper, director of the Commonwealth Political Studies Unit, “naivety” according to the labour MP and historian Tristram Hunt.

Sean Gabb, of the campaign group Libertarian Alliance, said Cameron should not apologise for Britain’s past. He said: “It’s a valid historical point that some problems stem from British foreign policy in the 19th and 20th centuries, but should we feel guilty about that? I fail to see why we should.”

He added: “Some of these problems came about because these countries decided they did not want to be part of the British Empire. They wanted independence. They got it. They should sort out their problems instead of looking to us”.

According to the Daily Telegraph (April 5, 2011), Cameron’s apparent willingness to accept historical responsibility for the Kashmir dispute “resonates with public apologies issued by his predecessors”. In 1997, former British prime minister Tony Blair apologised to the Irish people for the famine the country suffered in the mid-19th century. Later in 2006, he spoke of his “deep sorrow” for Britain’s historic role in the African slave trade. In 2009, former prime minister Gordon Brown issued an official government apology to tens of thousands of British children who were shipped to Australia and other Commonwealth countries between the 1920s and 1960s.

If the British political elite is confused by the desire to review the dark side of Britain’s colonial past, it is clear that the victims of this dark side have to line up in long queue waiting for an apology, half apology or a small gesture. And obviously Palestinian people will be at the end of the queue, and perhaps beyond.

British Prime Minister Theresa May is busy celebrating one of the most shameful pages in the British colonial past as she invited Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to visit London to attend the centennial celebrations of the Balfour Declaration, while an official statement of her government said “the UK refused to apologise to the Palestinians for the Balfour Declaration and the government was proud of our role In the creation of Israel”, according to the Independent.

“The Balfour Declaration is a historic statement for which HMG [Her Majesty’s Government] does not intend to apologise,” it said, adding “We are proud of our role in creating the state of Israel. The task now is to encourage moves towards peace.”

There are two points here in that statement that are full of unusual emotions — namely, the sense of pride about the creation of Israel and to encourage the move towards peace. Robert Fisk’s comments on March 2 in the Independent may be the most appropriate to show the true content of the Balfour Declaration. According to Fisk: “The implicit lie of the Balfour Declaration is that while Britain supports a Jewish homeland, nothing will be done that could harm civil and religious rights to the non-Jewish communities in Palestine.”

The simplest thing to say here is that the typical British colonial malice is clear and obvious. While the declaration explicitly refers to the national homeland of the Jews in Palestine, the original landowners of Palestine [Palestinian people] are fondly referred to as “non-Jewish communities in Palestine”, not more than “Others”. It’s the same malice and its favourite game of playing with words that is behind the formulation of the famous United Nations resolution 242.

Fisk has more about the hypocrisy of English politicians, adding that Boris Johnson, British Secretary of State, accurately wrote two years ago that the Balfour declaration was “strange” and a document that was “tragically unbreakable”, but in a subsequent visit to Israel, Balfour declaration was a “great thing” “reflecting a great stream of history”.

As for May, the reason of her feeling proud of Britain’s role in Israel’s establishment and her refusal to apologise to the Palestinians, is that, according to Fisk, “She needs Israel more than she needs Palestinians”. It is the same need for the votes of more than one million British voters of Indian origin that prompted Cameron to make that statement about the Jallianwalah Bagh massacre in India shortly before the 2013 elections in Britain.

Cameron did not tender those apologies, driven by moral or owing to any awakening of his conscience, but he was motivated solely by selfish interests and need. And it doesn’t seem to be aimed at all the victims of British colonial history. That is why he didn’t say a word about the tragedy that the Balfour Declaration caused to the Palestinian people for 100 years. On the contrary, his ethical blindness towards Israel led him to commit a violation of the long-lasting freedom of expression in Britain, whereas on February 15 last year, his government (without reference to the parliament) issued a memo to ministries and government institutions criminalising the boycott of Israeli goods and imposed harsh penalties for such boycotts on moral grounds — a move that many in Britain described as “a serious attack on democratic freedoms”.

Richard Gott wrote in the Guardian in July 2006: “The brutal story of the British Empire continues to this day”, and “This disastrous imperial legacy is still highly visible, and it is one of the reasons why the British Empire continues to provoke such harsh debate. If Britain made such a success of its colonies, why are so many in an unholy mess half a century later ...?”

Gott placed Palestine on top of the list of conflicts caused by the brutal story of the British Empire, but it is clear that the British colonial malice continues to this day, and English politicians are still committed to the core of what Balfour justified through his shameful declaration when he said that “The desires of 700,000 Palestinian Arabs are of no importance compared to the fate of a European colonial movement [Zionism] in essence”.

Mohammad Fadhel is an adviser in “b’huth” research centre in Dubai.