The world order, as we knew it until the end of the last century, has changed as a result of major developments, with crystal ball gazers still unsure about the shape of the new order replacing it.

This was also the tenor of a brilliant analysis of the changing world order presented by former Indian diplomat, T.P. Sreenivasan, whose last posting was as India’s ambassador in Vienna, Austria, and as Governor of India at the International Atomic Energy Agency.

During a recent interview with this writer on the sideline of his talk on the “Emerging World Order” — the event was jointly hosted in New York by the Global Organisation of Persons of Indian Origin (GOPIO), Sreenivasan maintained that the world is “in transition between an order that has very nearly died and an order yet to take shape”.

The transition journey, which started around 2000, has not yet been completed and, consequently, it is difficult to fathom the shape of things to come. But he maintained that the foundations of the post Second World War were demolished, though the shape of a new order was still not in view

Urgent collective action

Sreenivasan listed four major “game-changing developments in the early 21st century”: the destructive Sep. 11 attacks on New York’s World Trade Center, the economic meltdown that started with the sub-prime mortgage crisis, the globally devastating Covid-19 pandemic with its lockdowns and huge economic and human losses and, finally, Russia’s Ukraine invasion.

These four developments had impacted mankind, and shaken the world order as it existed until the turn of the century.

Before the Sep. 11 attacks, the world had seemed largely deaf to India’s warning about the upheavals that terrorism can cause to mankind. The Sep. 11 attacks also revealed the limitations of the world’s most powerful nation against determined individuals or groups.

However, despite the need for urgent collective action, the world was locked in hairsplitting semantics over the exact definition of terrorism.

Trajectory of international relations

The second game-changing development was the economic meltdown that affected the world in various ways, highlighting the interconnectedness and interdependence of economies. While the United States surmounted the disruptions, the impact of the crisis is felt even today.

Sreenivasan took a jibe at the United Nations Security Council which could not “meet even for a day” on the Covid-19 pandemic issue. The pandemic had exposed vulnerabilities in global governance and cooperation, showing the disparities in the world’s health care systems and the need for international collaboration to address the crisis.

Russia-Ukraine war raised concerns about international norms and behaviour of powerful nations. The complex dynamics involving Russia, Ukraine and other global powers had created uncertainty about the future trajectory of international relations.

Attention turns, invariably, to the United Nations whose purpose and relevance are increasingly questioned by critics. To them the world body has become a bloated global bureaucracy producing ever-rising mounds of paper and mired in a babble of tongues talking incoherent languages which are heard but not understood by anyone seeking justice or trying to redress any grievance.

And then, there is the perennial question of entrusting the world’s fate to five members — the so-called “permanent ones”, who believe that they will rule the roost forever, with their display of power, arrogance and protection of self- interest manifested in the veto right.

A sense of pride and achievement

India, which was recently crowned the most populous nation of the world, as if it were a sense of pride and achievement, is struggling to find its niche place in this changed world order. Still barred from entering the privileged club, as many contemptuously refer to the Security Council, India is trying to assert its position.

How long can the club go on guarding its exclusivity and treating the rest of the world as inconsequential? It may take years, nay decades, before some major catastrophe strikes the world and the process of review and rethinking sets in among those sitting on their high steed that they would have to come down and face the realities, and not consider themselves as privileged players with zero accountability.

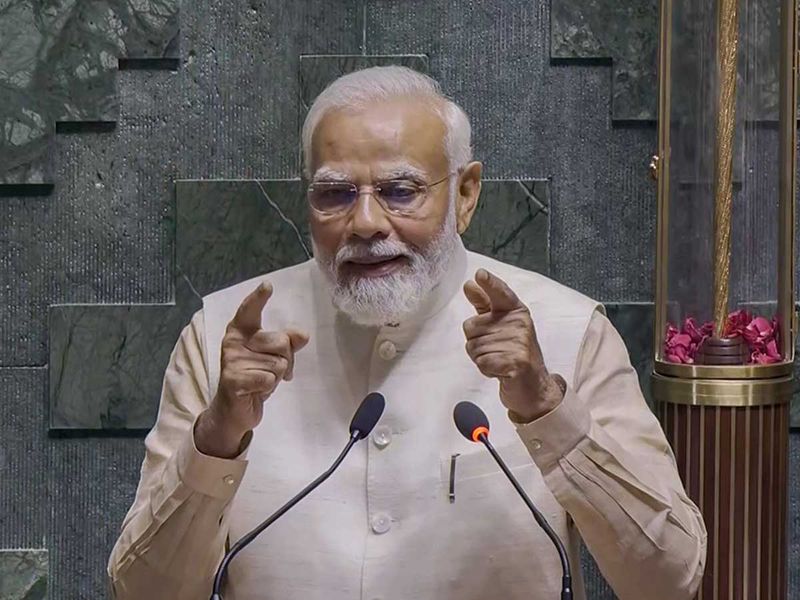

India is moving towards a better relationship with the United States. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi has clearly moved India towards the US. Modi, who will be on his first state visit to the US in June at the invitation from US.

President Joe Biden and the First Lady, held close talks with Biden in Hiroshima, Japan, where both were present for the G-7 summit and the Quad “side summit” which was also held there since Biden could not visit Sydney, Australia, the original venue of the Quad summit.

The question which is now uppermost in the minds of many thinkers is what position India would have in a multipolar world dominated by the two major powers, the US and China. India can have a dominant world role to play if it continued to add economic muscle power to its biceps and kept pace with technology, particularly artificial intelligence that will determine our future lives.

Indeed, India must not lose the present momentum of building up its economy, uplifting its people out of poverty and acquiring and deploying the latest technology, while not letting down the guard on both its conflict-prone borders.

Manik Mehta is a New York based journalist who covers foreign affairs and diplomacy, US bilateral ties, South Asia and global economics