The 50th anniversary of the civil rights marches in Selma and the movie that tells the story are expected to bring thousands of visitors to this historic Alabama city this year.

Visitors can still walk across the bridge where voting rights marchers were beaten in 1965 and see the churches where they organised protests.

“There are certain place names in American history where significant, history-making events took place, like Gettysburg, Valley Forge and Vicksburg, and I think because of this film, Selma becomes one of the place names that stands as a significant milestone in American history,” Alabama tourism director Lee Sentell said.

Oprah Winfrey, other actors from Selma and hundreds more marched to the city’s Edmund Pettus Bridge this past weekend on the eve of Martin Luther King Jr Day. But a bigger event is expected to attract more than 40,000 people — including present and former government officials — in Selma March 5-9 for the annual Bridge Crossing Jubilee, including a walk across the bridge March 8.

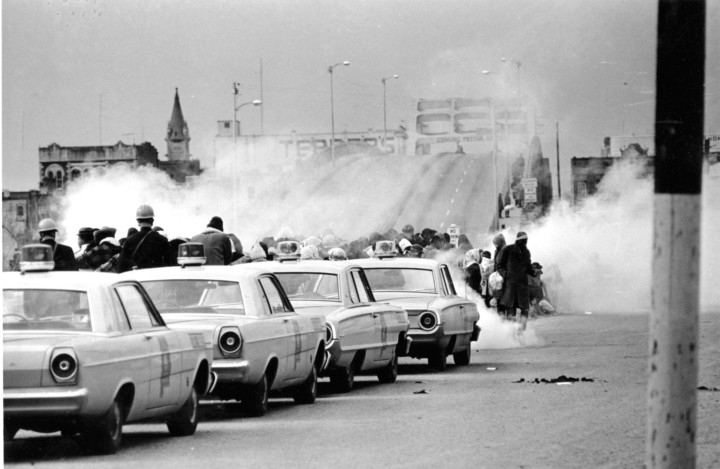

The event marks the 50th anniversary of the “Bloody Sunday”, when law enforcement used billy clubs and tear gas to rout marchers intent on walking 80 kilometres to Montgomery on March 7, 1965, to seek the right for blacks to register to vote. A new march, led by Martin Luther King Jr, began March 21, 1965, and arrived in Montgomery on March 25, with the crowd swelling to 25,000 by the time they reached the Capitol. Those events and others helped lead to passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, which opened Southern polling places to millions of blacks and ended all-white rule in the South.

The movie Selma won Oscar nominations for best picture and best song.

Today, the bridge and adjoining downtown business district look much as they did in 1965, except many storefronts are empty and government buildings are occupied largely by African-American officials.

Attractions related to the protests are all within walking distance of the bridge. They include the First Baptist Church, where many protests were organised, and Brown Chapel A.M.E. Church, where marchers congregated before going to the bridge and where they sought safety after being beaten.

Near the bridge, a free tour of an interpretative centre built by the National Park Service offers photographs of the events and emotional video interviews with people who were on both sides of the issues.

Nearby is the Ancient Africa, Enslavement and Civil War Museum, where visitors can see how slaves were captured, sold and exploited, including a depiction of what it was like to be on a slave ship bound for America.

“You have to know about slavery to know why we didn’t have the right to vote,” said Faya Rose Toure, one of the museum’s founders.

Then tourists can retrace history by walking across the Edmund Pettus Bridge to a park and the National Voting Rights Museum on the opposite side. Museum artefacts include surveillance photos taken by state police. One feature that stands out is the white plaster footprints of the largely unknown participants in the march and their personal stories about being part of history, from facing danger to treating blistered feet.

“Everybody has seen pictures of Dr. King leading the march. Those people behind him are what we are focusing on,” historian Sam Walker said.

State Senetor Hank Sanders, Selma’s first black senator since Reconstruction and a founder of the National Voting Rights Museum, said Selma’s location — an hour’s drive west of Interstate 65, a major route to Gulf Coast beaches — will help attract more visitors to the museum this spring and summer.

After touring Selma, visitors can drive the march route along US 80 to the halfway point in White Hall, where the Park Service has a much larger interpretative centre about the events. Then they can complete the 80-kilometre trip to Montgomery. There visitors can tour the Capitol, where King made the emotional speech that ends Selma, and see a monument and museum dedicated to civil rights martyrs.

The Civil Rights Memorial includes three victims featured in the movie, Jimmie Lee Jackson, who was shot by a state trooper; James Reeb, who was beaten by white segregationists; and Viola Liuzzo, who was shot by Klansmen while taking marchers back to Selma.

Other sites include the Greyhound bus station where Freedom Riders seeking to integrate interstate transportation were beaten by a white mob in 1961, a museum commemorating Rosa Parks and the Montgomery Bus Boycott that King led in 1955, and the Dexter Avenue King Memorial Baptist Church, where King served as pastor before moving to Atlanta to lead the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

Sentell, the state tourism director, suggests at least a day in each city. Visitors can also drive 145 kilometres to Birmingham to see the church bombing site featured in the opening of Selma and that city’s Civil Rights Museum.

Alabama’s governor, Robert Bentley, said the movie and the 50th anniversary of the Voting Rights Act are opportunities to relive history and see how Alabama has changed.

“Alabama is a different place than it was 50 years ago. We need to always remember our history, but we can’t live in the past,” he said.

___

If You Go ...

National Park Service Selma to Montgomery Trail: http://www.nps.gov/semo/index.htm

National Voting Rights Museum: http://nvrmi.com/

Alabama Tourism: http://alabama.travel/

Bridge Crossing Jubilee: http://www.bcjubilee.org/

Accommodations: The historic St. James Hotel, built in 1837 and located in the middle of Selma’s civil rights attractions, 334-872-3234.