On the campaign trail, Labour candidates congratulate people in marginal seats as the lucky holders of a “golden vote”. It is a way to express the importance of those races where the ballots of a select few can swing the national outcome for the many. The big parties’ morale is sustained by the hope of power secured with a well-targeted mailshot, nudging the right household to the polling booth.

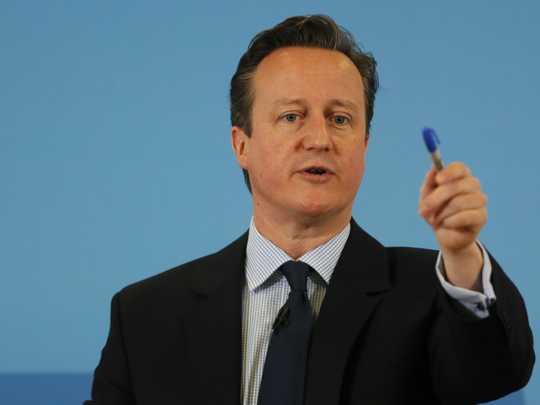

A great fuss is made of electors in Telford or Pudsey, as if they have found a Willy Wonka golden ticket, but instead of a lifetime supply of Whipple Scrumptious Fudgemallow Delight they get to choose between five years of Ed Miliband or David Cameron as prime minister. Grant Shapps, the Conservative chairman, claims that his party can win a majority if just 11,200 people in 23 seats turn Tory on May 7.

But this would only be true if every single other person could be relied upon to vote exactly as they did in 2010. (They will not.) This postcode privilege is a familiar feature of Britain’s first-past-the-post electoral system, but it feels doubly perverse this year. Opinion polls show little traffic between Labour and Tory camps, while smaller parties shape the national landscape by diverting votes from one of the big two. Away from the doorstep, candidates fume after encounters with voters intent (as they see it) on throwing away their golden tickets: Green supporters whose Leftist protest will abet Cameron; Ukippers inadvertently aiding Miliband.

Then there is the irony of locally popular Liberal Democrat MPs avoiding a deadly deluge in constituency lifeboats carved from the electoral system they wanted to scrap. The distribution of seats in parliament after the election will be an even worse replica of the will of the electorate than the current one. Reform of the voting system should obviously then be on the agenda.

Westminster and obvious have a troubled relationship. It was obvious in 2010 that money from lobbyists was scandalous But Westminster and obvious have a troubled relationship. It was obvious in 2010 that semi-idle MPs taking money on the side from lobbyists was scandalous — so much so that Cameron declared it “the next big scandal” after MPs’ expenses. It was also obvious that the House of Lords is ridiculous: An unelected legislature, stuffed so full of sine curists it is second in size only to the Chinese People’s Congress. Five years later, a Lobbying Act has been passed that is really a partisan swipe at campaigning charities and trade unions. Lords reform was killed in coalition crossfire. A Tory backbencher tells me he now regrets his sabotage of Lib Dem plans to redesign the upper chamber. (“The worst vote of my career,” he said.) The rebellion gave Nick Clegg a pretext to kill off changes to parliamentary boundaries that might, if enacted, have added 20 seats to the Conservatives’ likely election score.

But the principle of reform is also harder to dispute. Footage of Jack Straw, filmed undercover, advertising to a fake lobby firm potential uses for a peerage he has not yet officially got prompts even the stuffiest constitutional preservationist to think the system needs freshening up. Similarly, the complacency induced by a safe Commons seat was well expressed by Malcolm Rifkind — caught in the same sting operation — boasting of boundless leisure time, unimpeded by constituency duties or the pressures of chairing the Commons intelligence and security committee. He has now been forced to relinquish both functions.

Straw and Rifkind embarrassing themselves in grainy undercover TV pictures provokes a nauseating deja vu. It was at around the same point in the run-up to the last election that Patricia Hewitt (who was eventually exonerated), Stephen Byers and Geoff Hoon were busted in the same way. The whole episode adds to the pall of stagnation hanging over British politics: the deadlock in opinion polls, the war of attrition on the ground, the repetitive, unenlightening arguments between the main parties.

Tories attack Labour for having spent too much in government; Labour accuses Tories of planning gruesome butchery of public services. There is a budget deficit to clear, with the left flinching squeamishly from the task and the right sharpening its axe with unseemly relish. In the background Greece is at the centre of a Eurozone crisis. It is not 2010 repeated — we know history never does that — but it is a kind of historical tribute act, covering five years in which things that were meant to be fixed stayed broken. There isn’t even a decision yet on whether Heathrow should have another runway.

Politics is finding adaptation to the 21st century painful and slow, with the biggest players struggling to renew themselves. Cameron’s modernisation of the Tories stalled. Now his re-election bid is run by Lynton Crosby, architect of Michael Howard’s 2005 campaign. It will be more coherent than the 2010 effort, but likelier to project the old callousness that provokes allergic recoil in many voters. Miliband promised to “turn the page” on the Blair-Brown years, but he hasn’t illustrated the next chapter in colours that capture the public imagination. Even when the opposition message is delivered by fresh-faced shadow ministers, neither “old” nor “New” Labour, they look marooned between repudiation of what their party once was and confidence in what it should be instead.

It is wrong to say that British politics is rotten, although it does a regular line in stupid grubbiness. The air over Westminster is not foul with corruption but it is deathly stale. The choice between Labour and Tories at the next election is stark, with great consequences for the country, yet they are drifting into a campaign that feels in some ways eerily like the last one, only more desperate: Groundhog Day as it might be adapted for TV by the Parliament channel.

Questions that were already urgent at the last election will need addressing all over again, from the state of public finances to the probity of politics and the fitness of an archaic constitution. And this time parliament will be more fractious and the public less patient. The prime minister, whether Cameron or Miliband, will lead a ragged government stitched together from a few golden votes, with a clear majority of the electorate feeling unheeded and unrepresented, his mandate as flimsy as fudgemallow. He will not feel like a lucky winner for long.

— Guardian News & Media Ltd