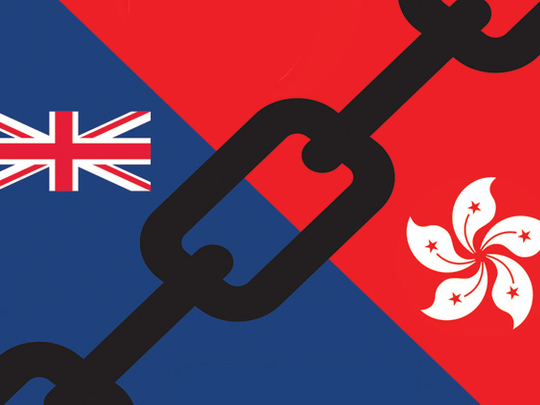

Anson Chan and Martin Lee have been in London. Veteran champions of freedom and the rule of law in Hong Kong, they were hoping for moral support in upholding the Joint Declaration under which, the territory passed from British to Chinese rule in 1997. They were greeted instead like prodigal distant relatives trying to barge back into the ancestral home. When Chan, the former head of the Hong Kong civil service, and the distinguished lawyer and politician Lee visited Washington a little while ago, they were received by Joe Biden, the US Vice-President. John Kerry was out of town, but the US State Department offered a serious hearing. British Prime Minister David Cameron’s Downing Street ruled they should see no one in London above a middle-ranking Foreign Office minister. The conversation went nowhere.

Thankfully, Nick Clegg, Cameron’s Liberal Democrat deputy in the Tory-led coalition, has an independent mind and received the two campaigners anyhow. Number 10, though, had sent the intended message to Beijing. China could be assured that Britain is not taking sides in the dispute about Beijing’s tightening grip on the governance of Hong Kong. The Foreign Office merely notes concern among some “commentators” about China’s dilution of past guarantees.

How things have changed. When Chan and Lee were in London a few years ago, they were feted by Cameron himself. The Tories, they were assured, would be stalwart in defence of Hong Kong’s rights and freedoms. It was Margaret Thatcher, after all, who had insisted that one China must have two political systems when she agreed the handover with Deng Xiaoping. That was before Cameron took office; and, more saliently, before the punitive freeze in bilateral relations imposed by Beijing after he had the temerity to meet the Dalai Lama, Tibet’s spiritual leader. The prime minister yielded, offering tribute to Xi Jinping, China’s president, during a trade mission to Beijing last year.

The message disseminated through Whitehall last week was that he did not want to find himself back on the naughty step. Clegg was left to wonder how it now falls to the Liberal Democrats to defend an agreement signed by Thatcher and ratified by John Major, her Conservative successor. Many in the business community welcome such reticence. The Occupy Central pro-democracy campaign has been roundly condemned by the Hong Kong offices of the big-four global accountancy companies — presumably at Beijing’s behest. Two London-based banks — HSBC and Standard Chartered — have abruptly withdrawn their advertising from Hong Kong’s Apple Daily, a newspaper backing recent street protests. The banks deny they were responding to Chinese pressure.

I suppose it was possible, if only just, to argue that Cameron’s crouch in Beijing was embarrassing, but ultimately inconsequential. Xi’s administration has made it clear that it sees Britain as a small power — a “historical relic” as the state-backed media likes to say. Neutrality over Hong Kong, however, is different. Even if one puts aside the profound moral obligation to the citizens of the formerly British territory, the Joint Declaration imposes a legal duty on the British government. Registered as an international treaty with the United Nations, it confers responsibility on both signatories.

Xi has decided otherwise. In keeping with his self-consciously assertive foreign policy, a recent Chinese white paper removed Britain from the script. The autonomy enjoyed by Hong Kong was at China’s discretion. Chris Patten, the last governor before the handover, has noted that a British government would never have signed any document as now framed by Beijing.

The white paper also chips away at the rule of law by suggesting the judiciary be seen as a branch of the administration rather than an independent guardian of the law. As for a long-planned extension of the suffrage for elections to choose Hong Kong’s chief executive, Beijing insists candidates must be screened to ensure that only those who “love China” are eligible. China and the Communist party are synonymous. All this adds up to a sustained effort to tighten Beijing’s grip on Hong Kong. Business and the media are under strong pressure to conform. To Chan and Lee — and to the tens of thousands who have publicly protested the proposed election rules — China wants to administer a political system more akin to that of authoritarian Singapore than to the, albeit constrained, autonomy envisaged in the Joint Declaration.

Cameron, some will say, cannot do much to stop this. The people of Hong Kong, however, are unlikely to accept meekly such decrees from Beijing. Some 800,000 took part in an online poll calling for a more open nomination process. If Britain is unwilling to speak out, where else can Hong Kong look for support?

The curious thing is that neither Britain nor business will profit from looking the other way. Weakness does not win special favours for British business from Xi. It does undermine Britain’s international standing. Washington wonders if Cameron’s government will ever take a stand on anything. And Hong Kong’s long-term prosperity rests, above all, on confidence in the inviolability of the rule of law. There is no need to pick a fight with Beijing, but Hong Kong’s freedom and Britain’s credibility in the world are inextricably linked.

— Financial Times