The United Kingdom’s general election is a little more than a month away, but already the campaign seems to have been with us forever, rolling implacably forward, but with little evidence of any genuine excitement – or even significant movement in the polls. Support for the two main contenders – the Labour Party and the ruling Conservative Party – seems stuck in the low-to-mid 30s.

The Conservatives hope that the government’s record on the economy will convince undecided voters to break in their favor late in the campaign. Maybe they are right; they deserve to be. In the meantime, Labour seems to be hoping for who-knows-what to turn the tide, while keeping their collective fingers crossed that they will not be eviscerated in Scotland, where the Scottish National Party is threatening to sweep the board.

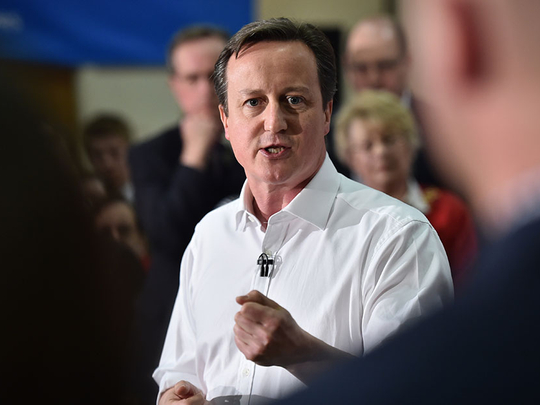

One surprise is the election campaign’s insularity. A dark cloud, in the form of a possible referendum on whether the UK will remain in the European Union hangs over the outcome, but no one talks about it much. Prime Minister David Cameron has said that a referendum is needed in order to prevent the country from sleepwalking toward an accidental and disastrous EU exit. And so it must come as a surprise to some of Britain’s EU partners that none of the country’s politicians seems to be making any effort to wake a somnambulant public.

More broadly, while much of the world seems to be going to hell in a handbasket, there has been little talk about Britain’s international role and responsibilities. The UK was once famous for punching above its weight in global affairs, but perhaps the country no longer really matters much – if only because it does not want to matter.

The closest anyone has come to putting some international fizz into the campaign was when US President Barack Obama fired a couple of warning shots across the UK’s bow. The Obama administration seems bent on proving that the so-called “special relationship” goes beyond raucous backslapping.

The first salvo – a warning that Britain should not be overly accommodating toward China – followed the UK’s decision to join China’s Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. But the problem is far broader than the AIIB. In any case, it is doubtful that anyone in London will take much notice. These days, policy on China is driven entirely by the Treasury, which subscribes to the view that one can do business with the Chinese only from a position of servility.

The second barrage was over a more serious matter, regarding defense spending. The criticism was directed at all European members of NATO, but it was clear that the US government believes that Britain bears a special responsibility to maintain its military commitments. The UK has a long track record of scolding its European NATO partners for not spending the 2% of GDP that each has pledged to dedicate to defense; now it appears that Britain itself risks falling short.

There is an economic argument against assigning a fixed percentage of national wealth to a given departmental budget. The British economy is now growing fast by current European standards, so 2% of GDP is becoming a larger sum. (The same is true of the UK’s similar commitment to the United Nations to spend 0.7% of its GDP on international development assistance.)

Government officials presumably recognize the embarrassment that would be caused were Britain to fall short of the 2% target, so they seem to be looking for programs that can be squeezed into the Defense Department’s budget to pad spending. This is exactly the sort of behavior the UK has criticized in others: lumping all sorts of pension payments and intelligence commitments into their calculations of defense spending.

There is a very real risk in all of this. The fact that neither of the major parties is prepared to make the case for increasing defense spending sends the wrong sort of message to Russian President Vladimir Putin. The proper response to Russian adventurism in Ukraine should not only be to work with the rest of the EU to help the government in Kyiv steady its economy; it should also include ramping up defense spending and convincing NATO members to do the same.

It is unfortunate that some of the most important issues facing the UK are being ignored in the country’s current election campaign. Whatever the outcome when voters head to the polls on May 7, the next government will have to deal with reality. The country’s defense posture and Russia’s threat to European security are sure to be near the top of the next prime minister’s agenda.

Chris Patten, the last British Governor of Hong Kong and a former EU commissioner for external affairs, is Chancellor of the University of Oxford.

Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2015. www.project-syndicate.org