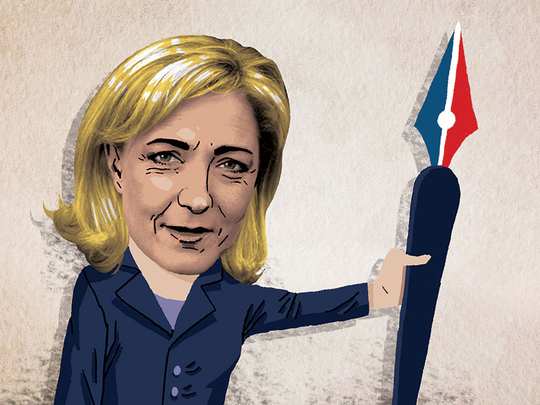

Marine Le Pen thinks careful language is the route to power. Jean-Marie Le Pen, her predecessor as leader of France’s far-Right National Front (FN), worries that his daughter’s craving for office will dilute the rabid xenophobia of the party he co-founded. My friends in Paris say they are both right. Shocking as the prospect is to outsiders, France is beginning to imagine a president Le Pen.

Today, Europe will watch the elections in Greece. Governments across the continent worry that victory for the populist Left Syriza party could provoke another crisis in the Eurozone.

My guess is that the immediate fears are overdone, though on its present trajectory the euro’s long-term future is far from assured. Never mind. If the present backlash against austerity in Greece could shake the European Union (EU), the rise to power of the FN in France would certainly break the 28-member union.

The Charlie Hebdo terrorist attacks brought an outpouring of national unity. The optimist in me says the mood may endure. Two of the heroes of the outrage — one a murdered police officer, the other a worker at a Kosher supermarket — were Muslims. Francois Hollande has been given a chance to rescue his ailing presidency. Manuel Valls has promised that necessary measures to tighten security against Islamist extremists will be accompanied by action to end the economic and social exclusion of much of France’s Muslim population — apartheid, the French Prime Minister calls it.

The politician who punctures such optimism is Le Pen. Shut out, and rightly so, from the demonstrations of solidarity, she could be the leader who profits most from the murders.

Across Europe, leaders of the populist Right have crafted a narrative that puts Muslim minorities alongside liberal capitalism, the EU and political elites as enemies of the people. Le Pen has notched up big victories in local and European elections. Recent polls suggest its leader would win the first round of a presidential contest.

What baffles me is the fatalism, some would say complacency, such a prospect engenders among large sections of France’s political class. Ask senior figures from the centre-Right or the socialist Left whether the FN’s unapologetic xenophobia is morally abhorrent, and the answer is yes. Yet the signs Le Pen is poised to capitalise on, Holland’s unpopularity and the disarray among conservatives, are greeted with a seeming shrug of resignation.

The other day, I sat in on a gathering of the French elites in Paris. The FN was at once conspicuous in its absence and present in almost every conversation. Yes, said the informal consensus, Le Pen could well make the second round of a presidential contest. And, yes, if she faced Hollande in the run-off, supporters of former president Nicolas Sarkozy might just decide to fall in behind her. Conversely, if Hollande were to fall at the first hurdle, many on the Left might prefer to loan their votes to Le Pen than support the loathed (by Socialists) Sarkozy.

What startled me about these conversations was the absence of anger and indignation. Perhaps I misread it, but the prevailing mood was “what can you do?” The economy is mired in a slump, unemployment is stubbornly high, Hollande will struggle to recover and Sarkozy’s return has reopened deep wounds within the centre-Right.

Anyhow, this narrative continues, Le Pen’s hopes of winning would demand she move further into the political mainstream. The leader, I heard, has already modified her opposition to French membership of the EU to concentrate her fire on the euro. And she has abandoned the overt racism and anti-semitism of her father’s generation of FN supporters. Jean-Marie Le Pen, we should all remember, has referred to the Holocaust as a “detail” of history. His daughter prefers whipping up fears that France is overrun by Muslims. He was an unapologetic demagogue; she chooses her words carefully.

This softening of its image, though, scarcely conceals the essential character of Le Pen’s party. Ethnic prejudice runs through its every pronouncement. The warnings about “Islamisation” are calculated to create a permissive environment for its thuggish supporters and to sow fear in the minds of the low-income and unemployed voters who have borne the brunt of economic failure.

Le Pen has no need to attack Muslims directly. She can raise questions about their “otherness” and about whether Islam and secular republicanism can ever sit easily together. Just as the anti-semitism of her father’s era questioned the allegiance of the Jews, Le Pen casts doubts on the loyalties of Muslims. The enemy, as ever with the ugly nationalism that Europe knows too well, is the outsider.

The FN prospectus, which includes unabashed protectionism and state control of big industries, runs counter to everything that Europeanism has been about since postwar reconciliation. It seeks to replace the Europe of the second half of the 20th century with that of the first. Its target is the liberal democracy that brought us peace.

Those now shrugging their shoulders are right when they say there is no magic riposte. That is no reason to surrender. The success of populism is the failure of mainstream politics. Le Pen can prosper only for as long as Hollande, Sarkozy and the rest fail to present a credible alternative. Europe must hope they have not left it too late.

— Financial Times