Washington: An FBI agent’s claim that a hacker may have exploited weaknesses aboard more than a dozen commercial flights, including sending commands to a jet engine in mid-air, has sparked new worries over the safety and cybersecurity of the nation’s passenger planes.

The hacker, a security researcher, said the FBI misinterpreted him, and jetmakers and security experts have cast doubt on claims that he was able to control a flight. But the episode has added to a mounting sense of vulnerability ahead of what’s expected to be the busiest summer for air travel in years.

The FBI investigation comes one month after more than 50 American Airlines flights were delayed due to a bug in a critical iPad flight-navigation app that pilots could fix only by nudging closer to an airport’s Wi-Fi.

And it comes only two months after the deadly crash of a Germanwings jet in the French Alps, caused by a co-pilot who locked the captain out of the cockpit and began the descent, killing all 150 people on board. Despite that tragedy and the cyber scares, air travel has never been safer — 20 commercial flights crashed last year, making it one of the safest in aviation history.

How it works: Click the infographic icon, top right

But a new wave of technology is raising questions about security for an industry that has long kept a tight grip on information flowing among pilots, air traffic controllers and top officials.

The aviation industry’s “previously centralised and controlled culture,” said Tim Erlin, a director at security software firm Tripwire, “is being forced to deal with the basic, but prevalent, security issues more open systems have been confronting for years.”

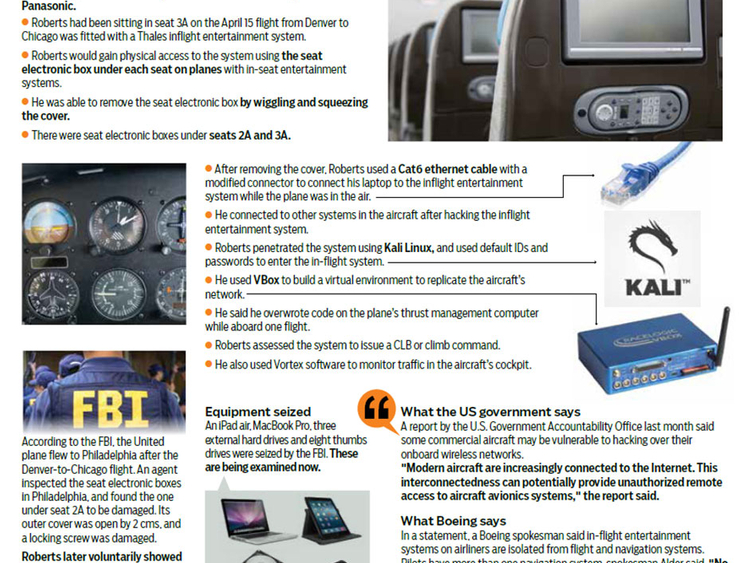

In an application last month for a search warrant, an FBI agent said researcher Chris Roberts had used a simple plug, installed beneath the seats of many commercial planes, to tap into in-flight entertainment systems up to 20 times since 2011.

From there, according to the FBI, Roberts said he was able to change code on a plane’s internal computers and even command a plane to climb and fly sideways. Roberts last month got agents’ attention by tweeting that he might “start playing” with his jet’s controls.

Roberts defended the tweet as a joke riffing off his previous warnings to jetmakers Airbus and Boeing over their planes’ security flaws, which he said could leave control systems for the plane’s cabin and oxygen mask systems open to attack. “My only interest has been to improve aircraft security,” he tweeted on Sunday.

But other aviation and security experts said the claims, of tapping into flight controls via a seat outlet, stretched the imagination, because entertainment and crucial flight systems are often kept separate. Hacking a plane’s engine controls through its entertainment system, they argue, is a bit like controlling a car’s steering wheel through its CD player.

Jetmakers defended their security against worries of a fleet-wide flaw. In Boeing jets, entertainment systems are kept separate from flight and navigation, pilots have multiple navigational systems at their disposal, and the jet’s flight plan can’t change without pilot approval, Boeing spokesman Doug Alder said.

“On every flight, there are multiple layers of security and procedures in place to protect passengers and crew,” said Victoria Day, a spokesperson for Airlines for America, the industry’s trade group.

But the industry came under fire in a Government Accountability Office report last month, which said that in-flight Wi-Fi networks on some Boeing and Airbus planes could allow an attacker to commandeer a flight.

Cockpit electronics connect to the same networks as the passenger cabin, and the firewalls that divide them can, as cybersecurity experts told the watchdog, “be hacked like any other software and circumvented.”

Security experts like Christopher Soghoian, who in 2006 built a tool exploiting an airline weakness by allowing people to print fake boarding passes, poked back at the industry itself, saying it had sacrificed security when it made features like the under-seat port, designed for entertainment systems, easily available to anyone.

“In order to show video ads to passengers,” Soghoian tweeted, “airlines placed an easy to access ‘hack this plane’ data port under every seat.”

Some of air travel’s biggest tech headaches have arisen from the same hazards troubling other industries. About 10,000 frequent flyers of American and United airlines were told in January their accounts had been compromised by hackers who booked themselves free or upgraded flights.