Johannesburg: A soccer referee named Ebrahim Chaibou walked into a bank in a small South African city carrying a bag filled with as much as $100,000 (Dh367,000) in $100 bills, according to another referee travelling with him.

Later that night in May 2010, Chaibou refereed an exhibition match between South Africa and Guatemala in preparation for the World Cup, the world’s most popular sporting event. Even to the casual fan, his calls were suspicious — he called two penalties for hand balls even though the ball went nowhere near the players’ hands.

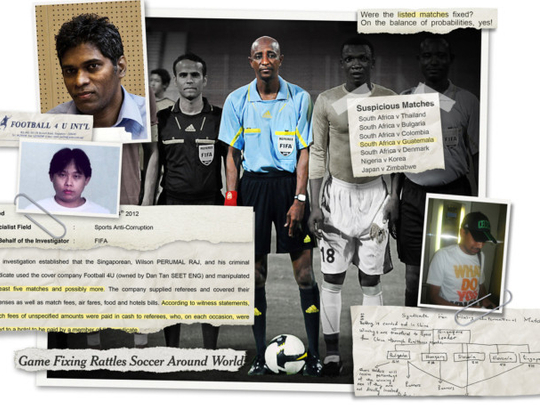

Chaibou, a native of Niger, had been chosen to work the match by a company based in Singapore that was a front for a notorious match-rigging syndicate, according to an internal, confidential report by Fifa, the soccer’s world governing body.

Fifa’s investigative report and related documents, which were obtained by The New York Times and have not been publicly released, raise serious questions about the vulnerability of the World Cup to match fixing. The tournament opens June 12 in Brazil.

The report found that the match-rigging syndicate and its referees infiltrated the upper reaches of global soccer in order to fix exhibition matches and exploit them for betting purposes.

It provides extensive details of the clever and brazen ways that fixers apparently manipulated “at least five matches and possibly more” in South Africa before the last World Cup.

As many as 15 matches were targets, including a game between the United States and Australia, according to interviews and emails printed in the Fifa report. The report, at 44 pages, includes an account of Chaibou’s trip to the bank, as well as many other scenes describing how matches were apparently rigged. “Were the listed matches fixed?” the report said. “On the balance of probabilities, yes!”

The Times investigated the South African match-fixing scandal by interviewing dozens of soccer officials, referees, gamblers, investigators and experts in South Africa, Malaysia, England, Finland and Singapore. The Times also reviewed hundreds of pages of interview transcripts, emails, referee rosters and other confidential Fifa documents.

Fifa, which is expected to collect about $4 billion in revenue for this four-year World Cup cycle for broadcast fees, sponsorship deals and ticket sales, has relative autonomy at its headquarters in Zurich. But The Times found problems that could now shadow this month’s World Cup.

— Fifa’s investigators concluded that the fixers had probably been aided by South African soccer officials, yet Fifa did not officially accuse anyone of match fixing or bar anyone from the sport as a result of those disputed matches.

— A Fifa spokeswoman said Friday that the investigation into South Africa was continuing, but no one interviewed for this article spoke of being contacted recently by Fifa officials. Critics have questioned Fifa’s determination and capability to curb match fixing.

— Many national soccer federations with teams competing in Brazil are just as vulnerable to match-fixing as South Africa’s was: They are financially shaky, in administrative disarray and politically divided.

Ralf Mutschke, who has since become Fifa’s head of security, said in a May 21 interview with Fifa.com that “match fixing is an evil to all sports,” and he acknowledged that the World Cup was vulnerable.

“The fixers are trying to look for football matches which are generating a huge betting volume, and obviously, international football tournaments such as the World Cup are generating these kinds of huge volumes,” Mutschke said. “Therefore, the World Cup in general has a certain risk.”

Chaibou, the referee at the centre of the South African case, said in a phone interview that he had never fixed a match, and he denied knowing or having ever spoken to Wilson Raj Perumal, a notorious gambler who calls himself the world’s most prolific match fixer and whom Fifa called one of the suspected masterminds of the South Africa scheme.

“I did not know this man,” Chaibou said. “I had no contact with him ever.”

Chaibou said Fifa had not contacted him since his retirement in 2011. He declined to answer any questions about money he may have received in South Africa.

The tainted South African matches were not the only suspect ones. Europol, the European Union’s police intelligence agency, said last year that there were 680 suspicious matches played globally from 2008 to 2011, including World Cup qualifying matches and games in some of Europe’s most prestigious leagues and tournaments.

“There are no checks and balances and no oversight,” Terry Steans, a former Fifa investigator who wrote the report on South Africa, said of the syndicate’s efforts there in 2010. “It’s so efficient and so under the radar.”

As players from South Africa and Guatemala gathered for their national anthems, Chaibou stood between the teams at midfield. He was flanked by two assistant referees who had also been selected by Football 4U International, the Singapore-based company that was the front for the match-rigging syndicate. They were present because of a shrewd maneuver the fixers had begun weeks earlier to penetrate the highest levels of the South African soccer federation.

A man identifying himself as Mohammad entered the federation offices in Johannesburg carrying a letter dated April 29, 2010. The letter offered to provide referees for South Africa’s exhibition matches before the World Cup and pay for their travel expenses, lodging, meals and match fees, taking the burden off the financially troubled federation. “We are extremely keen to work closely with your good office,” the letter read.

The offer sounded strange to Steve Goddard, the acting head of refereeing for the South African Football Association at the time. He knew that Fifa rules allowed only national soccer federations to appoint referees. Outside companies, like Football 4U, had no such authority.

Several days later, Goddard said, Mohammad returned and offered him a bribe of about $3,500, saying he was holding up the deal. Goddard said he declined the offer.

Nevertheless, other South African executives moved forward with Football 4U. At least two contracts were drafted, giving Football 4U permission to appoint referees for five of the country’s exhibition matches. The Fifa report called the contracts “so very rudimentary as to be commercially laughable.”

Fixers are attracted to soccer because of the action it generates on the vast and largely unregulated Asian betting markets. And if executed well, a fixed soccer match can be hard to detect. Players can deliberately miss shots; referees can eject players or award penalty kicks; team officials can outright tell players to lose a match.

Before the match, the betting line had been 2.68 goals, an ordinary number, said Matthew Benham, a former financial trader who runs a legal gambling syndicate in England. By kickoff, the expected goals rose drastically, to 3.48, and then to more than 4 during the match, Benham said. The final score was 5-0.