Guantanamo Bay, Cuba: Twice a day, every day here, some 20 men have a tube forcibly inserted into their nose. It is directed down to the stomach and then liquid protein is pumped in as they sit restrained by their head, chest, arms and feet on a metal feeding chair.

These men — some of the 127 detainees held by the US military in maximum security jails on the southwest coast of Cuba — are still fighting back. They are classified as “noncompliant” — they don’t follow the rules, still curse the US and its jailers and refuse to eat. Most have been held here for the last 13 years. And most do not know when they are going home — if at all.

Gulf News is the first newspaper in the Gulf to be permitted into Guantanamo Bay, one of the most secret and secure places on Earth and a place whose name has become synonymous with the dark side of America’s “War on Terror”, torture, hunger strikes, quasi-judicial military courts and men in orange jumpsuits.

Take an interactive tour of Guantanamo Bay

US President Barack Obama had ordered the closure of the controversial prison here on January 22, 2009. Six years on, they are still open.

When Gulf News was permitted inside, there were 142 detainees. At the height of its operations, the camps held 779 detainees. Most there have never been charged, most have been tortured and most do not know if or when they will ever be released.

Most are like Obaidullah, an Afghan shopkeeper who has been in Guantanamo since October 2002 and has never faced trial.

“We would love Obaidullah to have his day in court,” explains Anne Richardson, his lawyer in Los Angeles. “He is a very intelligent, compassionate, caring individual, one whose personality and everything that I have seen about him for the past seven years is completely at odds with the notion of being a member of the Taliban.”

Obaidullah is considered to be “fully compliant” — he follows the rules. For that, he gets two changes of clothes, some books, basic toiletries and gets to live in a cell in a community block in Camp VI, can sit with the others at stainless steel tables, watch television, exercise in a small yard during daylight hours — and his cell door is left open for all but two hours every day.

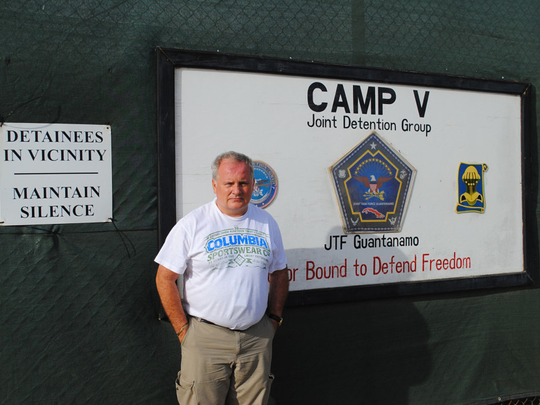

The “noncompliant” are held in Camp V. They live in their cells for 23 hours a day and get only limited exercise. Everything that goes into these cells is closely examined to see what comes out. And if a detainee consistently refuses to eat, he is put on the force-feeding regime. The US military, however, refers to the process as “enteral feeding”.

‘My call’

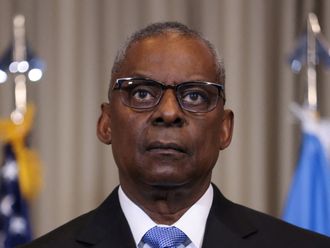

“When the decision comes to enterally feed a detainee, ultimately it’s my call,” Real Admiral Kyle Cozad says. He is the Commander of the 2,500 military personal who operate the Joint Task Force (JTF) Group in Guantanamo Bay.

“It’s a last resort. It’s not a disciplinary measure. It’s made under medical and nutritional guidance. I consult with my Senior Medical Officer and it’s a last-resort option for us. We take the decision to enterally feed a detainee when the patient’s medical conditions are such that the doctor has a concern. We have robust but limited medical facilities on the island.”

And yes, Cozad has himself observed a feeding process, adding that the method is the same as the one used by the American Medical Association and the US Bureau of Prisons.

But in the US prison system, inmates have the right to independent counsel, appeals, judicial process ...

“The individuals here aren’t inmates,” Cozad counters. “They are detainees. They haven’t been convicted. They are held under law of war detention standards. As such, there are some things that make this different from a correctional institution,” he adds.

“The treatment of the detainees is safe, legal, humane and transparent and complies with Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions,” Cozad tells Gulf News. And as far as allegations of torture or abuse, that might have occurred at the base, are concerned, he says nothing of that sort happened “on my watch” that began in July 2014.

And Rear Admiral Cozad is also responsible for the 15 ‘most-prized assets’ — the top of the terror chain picked up from around the world and accused of masterminding the attacks of 9/11, countless murders, bombing and the deaths of thousands.

These 15 are held in Camp VII — a facility so secret that the US military, up until the visit by Gulf News to Guantanamo, had declined to acknowledge or even admit its existence. Khalid Shaikh Mohammad from Pakistan, considered to be the No 3 man in Al Qaida behind Osama Bin Laden, is held there. He has acknowledged being the mastermind of 9/11, the Richard Reid shoe bombing attempt to blow up an airliner, the Bali nightclub bombing, the 1993 World Trade Centre bombing, the murder of Wall Street Journal reporter Daniel Pearl and various foiled attacks. He has been water-boarded 183 times — something that the US authorities have acknowledged. He has also been sleep-deprived for a week — an episode that his CIA captors say finally broke him.

He is under trial and faces the death penalty if convicted. Alongside him, when he appears at Camp Justice hearings, are his four co-accused: Two Yemenis, a Saudi and another Pakistani. And they have been tortured too or, as the CIA puts it, questioned using “enhanced interrogation techniques”.

Colonel David Heath is in charge of the JTF guard force — the men who are the jailers. Heath provides Gulf News with a breakdown of where the detainees are held.

“I’ve got 15 in Camp VII — they are my high-value detainees. I’ve got 67 in Camp VI and the rest in Camp V.”

He says the military are involved in the running of the day-to-day operations of Camp VII, along with the other two camps.

“I make day-to-day operational decisions for that facility,” Col Heath adds.

Under further questioning by Gulf News, a senior Public Affairs Officer present during the interview halts the proceedings. Because of “OpSec” — operational security — rules, while Col Heath can be identified, most personnel on the base can’t be photographed. And there are strict rules regarding what exactly can the military say to protect the secrets of Guantanamo Bay.