Dubai: On May 30, 2014, less than 100 hours after being sworn in, the Narendra Modi-led government at the Centre was confronted with its first crisis of sorts: A tripped grid in Uttar Pradesh had snapped power supply in parts of northern India and plunged capital New Delhi into darkness as well.

What followed over the next 24 hours could easily be archived as an emergency-response manual for government departments.

Barely days into his new role as the Union Power Minister, Piyush Goyal transformed his office into a virtual war room as he personally monitored the repair and restoration work on the Northern Grid.

For 24 hours, he did not move from his cabin -- issuing orders, deploying personnel, liaising with various Union and state government departments and keeping the Prime Minister’s Office abreast of the developments all the while.

Modi’s poll campaign promise of “minimum government, maximum governance” had a baptism by fire! And both the PM and his junior minister came out all guns blazing as the grid came back to life.

If such administrative activism and a hands-on approach to governance mark one side of the coin, then the other side bears the forebodings of a demand-supply imbalance in terms of public aspiration levels over the last 12 months that continues to keep the establishment on its toes.

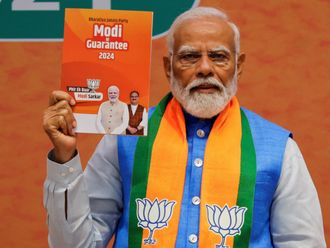

With the Bharatiya Janata Party government under Modi’s stewardship set to complete its first year in office on Tuesday, it is time to look back and take stock of the hits and misses.

Economy: Missing big-bang reforms (5/10)

The very first thing that helped Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi strike a chord with the electorate at the first election rally that he addressed in Rewari, Haryana, in August 2013, was his promise of shaking the Indian economy out of its slumber. Twelve months and one budget later, Finance Minister Arun Jaitley’s serve-and-volley game has left expectations of big-bang reforms unfulfilled.

True, early last month, acclaimed agencies such as Fitch and Moody’s gave India improved ratings. While Moody’s Investors Service raised India’s credit rating outlook to positive, Fitch Ratings boosted its growth forecast on India, thereby generating some positive vibes about Asia’s third-largest economy.

Fitch has forecast that India will expand 8 per cent in the year through March 2016, from 7.4 per cent in the previous 12 months. But there are glitches galore that Jaitley will take some time to iron out.

The lack of consensus among political parties over the Land Acquisition Bill being a case in point. If the logjam over the bill continues, the Modi government’s plans for the development of smart cities, airports and a quadrilateral of high-speed rail network may all die a silent death on the drawing board.

Added to that, of course, is the issue of farmer suicides. The death of 15,000 farmers annually over the last two decades surely points to a deep-seated crisis.

Two factors, however, have given the Finance Ministry mandarins enough latitude to play on: falling oil prices in international markets and the slowing of domestic inflation.

Foreign policy: Reinvigoration and reanimation (7/10)

How many air miles has PM Modi clocked in his first year in office? A good quiz question -- or so one thought. But the point is when did India last have a prime minister who could say this in the presence of an American president: “There is such a strong bond of friendship between me and [US President] Barack [Obama] that we can just pick up the phone and indulge in small-talk anytime we want!”

Yes, this was exactly what Modi said as Obama regaled in the former’s presence at a joint press interaction at Hyderabad House in New Delhi this January.

If the Modi-Obama bonhomie marks a new high in India’s relations with the world’s most powerful economy, then no less significant is the fact that India’s neighbouring states of Bhutan and Nepal were among Modi’s first few foreign destinations after being sworn in on May 26, 2014.

Handling of the tricky Yemen evacuation and dispatching Foreign Minister Sushma Swaraj to Dhaka to prepare the pitch for an Indo-Bangladesh summit meeting have all reshaped India’s foreign policy doctrine, marking a very clear and bold departure from the staid Manmohan Singh-era. There is no denying that Modi’s ‘selfie’ with Chinese President Xi Jinping has generated a lot of positive vibes well beyond the red sandstoned confines of South Block.

Home affairs: Spectre of majoritarianism (5/10)

Contrary to what many sociopolitical observers had predicted, India has not had any serious communal flare-up in the first 12 months of a BJP-led government at the centre. However, what is rather unfortunate is the fact that in these 12 months, on multiple occasions, Union Home Minister Rajnath Singh has had to appeal to his own party men to desist from practising hate speech and incitements to violence.

BJP leaders such as Sakshi Maharaj and Union minister Sadhvi Niranjan Jyoti have made senseless comments against minority communities, making a travesty of Modi’s pre-poll promise of Sabka Saath, Sabka Vikaas (with all, towards progress).

Incidents of conversions to Hinduism, in the name of ghar wapsi (homecoming), have only added fuel to the fire of religious intolerance as perceived to be propagated by the saffron regime under the tutelage of Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh.

Defence: Exorcising the bofors ghost (6/10)

Legend has it that at one point of time, during the erstwhile Congress-led United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government, not a single file for new defence purchases moved from defence minister A K Antony’s desk for fear of being besmirched by kickback scams, particularly in light of the botched AgustaWestland helicopter deal.

However, the Modi government has managed to exorcise fears of a Bofors-like scandal in striking defence deals. During Modi’s visit to France, firm orders for 36 new-generation Rafale fighter jets were placed at an estimated cost of $5.5 billion (Dh20.2 billion). The landing of a Mirage 2000 fighter jet on Yamuna Expressway, as part of an emergency drill last Thursday, further shows that the government is ready to think out of the box.

However, border skirmishes with Pakistan and incursions by China in India’s Northeast continue to be sore points. Similarly, India’s plans of further fortifying its territorial waters in the Indian Ocean and its ambition of a bigger presence in South China Sea to keep China on tenterhooks are fraught with danger.

Social drivers, transparency quotient: Win some, lose some (5/10)

One of the biggest let-downs of the Modi government has come in the form of diminished emphasis on welfare spending for 330 million of India’s 1.2 billion people. If the Railway Budget impressed by not proposing a single new train, focusing on safety and passenger amenities instead, then neglecting welfare schemes to fund infrastructure projects is surely not going to warm too many hearts.

Secondly, in spite of all the tall claims to retrieve black money from offshore accounts, so far, all that the government has managed is a partial list of names of offenders who are mostly considered small-fry.

Moreover, all ministerial decisions are centralised with the prime minister’s office, leaving little wiggle room for the Cabinet.

On the brighter side, the allocation of coal blocks and telecom spectrum auctions were conducted in a very transparent manner, in a complete departure from the muddled state of affairs under the UPA rule. In its first year in office, this government has managed to keep the issue of corruption at bay and that’s a huge plus.

Conclusion

With his launch of the Swachh Bharat (Clean India) campaign, Prime Minister Narendra Modi was spot-on, so far as his ability to feel the pulse of the masses was concerned. Ditto for creating a separate Cabinet portfolio for cleaning up River Ganga.

However, loose cannons within his own party and over-zealous satraps in the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh have time and again put paid to Modi’s ambitious forays as a statesman with a pan-India discourse.

Indeed one year is too short a time to label a government a success or a failure, though the ‘pings’ from the socio-political and economic ‘transponders’ can still be picked up all the same.

And going by those ‘pings’ one can say with a fair bit of certainty that matching the optics of a poll promise with the pragmatics of governance will be the Indian prime minister’s biggest challenge in the days ahead.