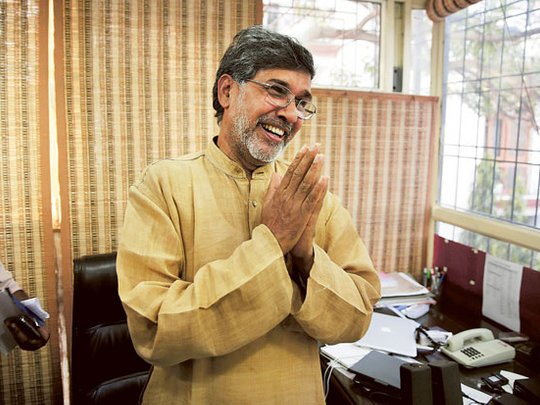

New Delhi: Kailash Satyarthi is a real life hero for thousands of young children, who have been freed from the clutches of unruly employers in daring rescue missions in the last more than three decades. Recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize, he has as many injuries on his body due to these missions as the numerous international awards he has won.

Facing stiff resistance, including firing at several places, he has refused to leave the premises and managed to rescue children from captivity. Originally from Vidisha in Madhya Pradesh, Satyarthi moved base to New Delhi in 1980 at the age of 26 and launched Bachpan Bachao Andolan (Movement to Save Childhood), a non-profit entity fighting for child rights and education.

On initiating a crusade against bonded labour and child servitude in the manufacturing of rugs, Satyarthi was branded a foreign agent out to destroy the carpet industry. A commoner, he fought battles in a number of states including West Bengal, Uttar Pradesh, Orissa, Jharkhand and Delhi, and refused to let anyone deter him for working towards uprooting the social evil from society.

The award might just be another honour for his work, as he goes about relentlessly pursuing what he set out to do. The candle of child rights activism that Satyarthi lit in his 20s has now become a fire. For, apart from freeing children from forced labour, he has also successfully created international awareness about child workers issue by organising global marches.

He has been a front-runner in pushing for laws against child labour and trafficking in India. Satyarthi’s efforts eventually lead to a Constitutional amendment that paved the way for the Right to Education Act, which guarantees compulsory education for all children in the country below the age of 14.

His organisation Bachpan Bachao Andolan (BBA) has since long engaged with police, public and administration to conduct raids in various corners of the country to rescue children who are brought into the labour force.

In 1998, he organised the Global March Against Child Labour across 103 countries, which helped pave the way for an International Labour Organisation convention on the worst forms of child labour.

Satyarthi is also founder of RugMark (now known as Goodweave), an international consortium of independent bodies from a dozen carpet exporting and importing countries. They take part in a voluntary social labelling initiative to ensure that rugs have not been produced with child labour.

Satyarthi shares the Nobel award of US$1.1 million (Dh4.4million) with 17-year-old Pakistani girl Malala Yousafzai, the youngest winner of the coveted prize. Malala was shot in the head by the Taliban while going to school in 2012. She displayed tremendous courage even after the Taliban attack when she expressed her determination to carry on with her campaign for child rights and girls’ education, especially in Pakistan.

Proud of the youngster, Satyarthi, who dropped his surname Sharma for a caste neutral name Satyarthi, said he had invited Malala to join an additional dimension in the fight for child rights — that is the right to be free. A messiah for India’s close to 50 million child workers, he has rescued and rehabilitated more than 80,000 child labourers.

He spoke to Gulf News in an exclusive interview.

GULF NEWS: It is said the seeds of activism were sowed in your life at an early age.

KAILASH SATYARTHI: Yes, it began at the age of five, when I was in school and one day saw a child working alongside his father, a cobbler. It left an indelible mark on my psyche and during by childhood and adolescence I wanted to work against child labour, but without knowing at that time how to do it.

When did the first child rescue operation happen?

It happened in 1981 at a brick kiln in Sarhind, Punjab. We were publishing a magazine called Sangharsh Jaari Rahega (The Struggle Will Continue) and father of a 13-year-old girl approached us with his daughter’s story, who was forced to work as child labourer. He was wanting us to publicise his plight, as he could not do anything to rescue her. We realised it was not just a matter of writing about the issue. We had to act to save her, as she was about to be sold to a brothel. We managed to rescue her. Just as in her case, whenever a child is rescued, I feel I am being freed.

Which countries are you focusing on?

I feel proud to say that my fight for child rights began from India and it later spread to other countries. When I started talking about the rights of children in 1981, the United Nations convention on children’s rights had not yet been born. The UN convention on the rights of the child was adopted only in 1989. I was working as an engineer then and quit my job and started BBA. Despite limited manpower and resources, we work in thousands of villages in India and over 140 countries, including Pakistan, Africa and Latin America and have strongly believed in the principles of peace and non-violence. Child labour is an international problem and more than 170 million children across the world are victims of child slavery.

On what premise are the young children forced to work?

They are falsely promised a good life and plenty of money, which would rid them of poverty. But they are forced to work in zari units, textile mills and other industries and as domestic helps.

What major misconception do people have about child labour?

It’s a myth that poverty leads to child labour. The fact is child labour causes poverty because it leads to illiteracy. There can be no jobs without education, so the uneducated remain poor. Our biggest challenge has been to change social mindsets and make people aware that child labour is a social evil. BBA has been running several public awareness campaigns and making efforts to publicise the problems of child labour. These include a programme run in rural India to push for the enrolment of children in schools.

What steps should countries take to protect children from exploitation?

People must boycott products and services that involve children. And they should have the courage to tell the employers they are boycotting their place or deciding against buying products from their store, because they are hampering the interests of children, which is a crime. This will surely put psychological pressure on the industries that employ children.

Do you feel the pressure the Nobel Peace award has brought with it? What has changed for you ever since?

Nothing much has changed, except receiving too many phone calls and too many visitors! That apart, I feel much more moral responsibility towards the most deprived children as well as peace in the world. We have to create an environment not only in India and Pakistan, but globally, where no child is born and forced to live in the situations of war, terror and conflict and every child should be able to enjoy childhood in a free and fearless environment.

Would the prize money be of help in making new beginnings on some front, which hitherto could not be accomplished due to financial constraints?

I have already declared that every single penny of the award will go for the cause of children of the world. I would certainly like to put emphasis on women and child trafficking in particular and see how education can also be brought together with these. We see that intolerance is growing fast and it is required that children and youth be engaged for the purpose of non-violence and peace all over the world. But first of all they have to be free from exploitation and slavery. It is not very clear how we will combine these issues, but I did speak to Malala about it.

With your experience in the field of child rights, what advice, if any, did you pass to or would like Malala to follow?

We have to see how to work together on child rights because there is lot of commonality. So, it is not just about terrorism, child labour is violence, depriving them of childhood is violence and poverty is violence. Now we need to broaden the definition of violence and see how to work in the broader spectrum of violence including illiteracy, human trafficking and child labour.

What kind of assurance have you got from Prime Minister Narendra Modi regarding child labour, in view of the fact that he was once a tea boy?

I did meet him, but did not discuss this in the courtesy meet. He was very excited and open to work on such issues but nothing was very specific. My call to him was that when we are creating a clean, bright and powerful India, all these could be sustainable only when we create a child-friendly India. I am trying to add child-friendly India with his vision and mission.

Why are the figures not convincing enough, despite a complete ban on child labour in the country for the past seven years?

By way of our Global March initiatives, we have been trying best to convince countries to ban any kind of child labour up to the age of 14, or even 18. We worked upon the issue with the previous government and it is in the pipeline to be also discussed with the present government.