Damascus: For more than 20 years, the Storyteller of Damascus entertained crowds in a centuries-old cafe in the Syrian capital with long, poetic tales of Arab warriors and lovers, acting out scenes with his fists thumping and a sword that he’d swing and slam on a table. Rashid Hallak was the most famous of the few remaining “hakawatis” in Syria — traditional reciter-performers of old Arab legends.

Now he’s a 70-year-old broken man, his life upturned by Syria’s war. “I am the Storyteller of Damascus,” Hallak said, chain-smoking, in an interview in the Syrian capital. “In these events, many people were harmed. I am one of them.”

The war, now in its fourth year, cost him his job and his home, destroyed in shelling. He’s among the more than 9 million people driven from their homes in a war that has killed more than 160,000, levelled parts of cities and unravelled the country’s social fabric — with no end in sight as rebels and the forces of President Bashar Al Assad battle.

Throughout its 300-year existence, the Al Nofara cafe in Damascus’ stone-built Old City has always had a hakawati telling stories in evening gatherings, said the cafe’s owner Mohammad Rabat.

But the art withered as Syrians turned to TV for entertainment. By 1990, the cafe was scrambling to find somebody, he said.

Hallak was picked because he used to read the hakawati’s books as a child in the Al Nofara cafe, where his father was a patron. Few people can understand the thick old tomes, with their jumble of Arab dialects, peppered with Turkish.

When asked to work, Hallak was surprised. “Is it possible? People want a hakawati, in this age, when we have gone to the moon? When there is television?’”

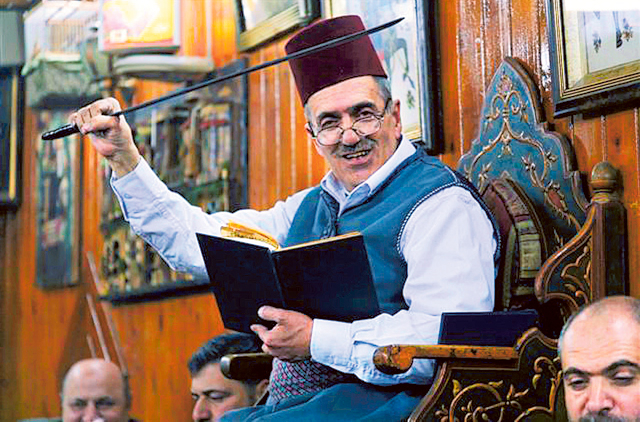

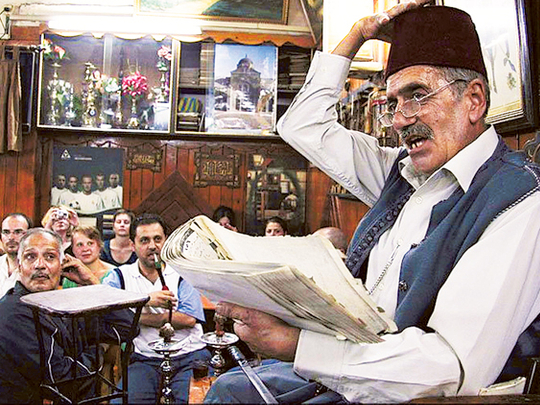

Still, he donned the hakawati outfit: baggy pants, a brocade-belt sash, a brimless hat, and settled in the storyteller’s high chair, overlooking patrons in the tiny, smoky, high-ceilinged cafe.

Locals were delighted by his theatrics as he told stories. The most popular was the tale of the pre-Islamic hero Antar, son of a black slave woman, famed as a valiant fighter-poet who fought for his beloved, the beautiful Princess Abla. Evenings with the Storyteller of Damascus, as he dubbed himself, were a favourite for tourists, and he appeared on television and performed in theatres.

But the cafe’s fortunes sagged as the war drove tourists and Syrian customers away. By early 2012, Hallak was reduced to two shifts a week.

Meanwhile, his rural town of Ghouta, east of Damascus, was a contested area, battled over by government troops and rebels — and awash with criminals taking advantage of the war’s chaos. Hallak’s home was looted, and masked men threatened to kidnap his son Shady for ransom. Shady fled to neighbouring Lebanon.

Crossing through rival rebel and pro-government checkpoints in town could be deadly — and Hallak was never sure how to appease each side. Rebels suspected him because the Syrian cultural icon didn’t express support for the uprising. Yet Hallak says he agrees with demands for reform expressed by Syria’s tolerated internal opposition. He stopped trying to reach Damascus, ending his shrinking career.

Then, his house was shelled last year while he was in his grocery store downstairs, the family’s side income. His house was demolished, and a girl in his shop and young man nearby were killed.

It broke the storyteller.

“When you see a little girl dying of shrapnel, because she is buying something in your shop — what remains of your health?” said Hallak, bursting into tears.

“Everything I had was destroyed,” he said. His family fled, and he has no idea what happened to his possessions — particularly his books, including a rare 30-volume set of Antar’s legends.

Hallak and his wife joined his son in Lebanon. In January, they all returned, moving into an apartment in central Damascus after he was offered a storytelling series on Syrian television.

But he has to keep the stories to a short 15 minutes.

“Nobody has patience to listen for an hour anymore,” he said, mourning the distractions of the modern age: “Everybody has WhatsApp.”

And to his dismay, he discovered he’d been replaced at the Al Nofara by a new hakawati, 55-year-old Ahmad Laham.

Laham held court on a recent afternoon in Al Nofara, which was nearly empty, with eight men and women smoking waterpipes. With the once deep-into-the-night social life of pre-war Damascus now gone, Al Nofara gets few patrons and closes down early these days, 8 pm maximum, said the owner, Rabat.

The new hakawati looked down from his glasses to read the 13th century tale of Beibars, the hulking blonde Muslim warrior and Mamluk ruler of Egypt who fended off crusaders and the invading Mongol hordes.

Laham sometimes stumbled over difficult words. The patrons sometimes joined in to recite a well-known chorus.

Behind Laham, the wall was plastered with images and photos: a younger Hallak” Abu Ahmad, a hakawati who died in 1951” a flamenco dancer and a painting of Abla, the beloved of Antar.

Laham, too, said he began by reading the books of the hakawatis, and when he was middle age, began offering his services as a storyteller.

“This is my passion,” he said, blushing slightly.

“I’d say he’s good, not excellent, but not bad,” Rabat said of the new hakawati, waving his hand to indicate “so-so.”

“They could have asked me,” Hallak sniffed.

His first love being cafes, not television, Hallak said he was looking for another place to be a hakawati.

This time, he’s less interested in orating old legends. “I have a wish,” he said. “To tell the stories that are about the truth.”