Shortly after the people rose against the Syrian government in 2011, protesters in the city of Homs shredded a banner that carried the face of the late president Hafez Al Assad, the dictator who ruled his country for 30 years with unrelenting ruthlessness; the man whose son embarked on the war that has claimed the lives of thousands.

As Zaher Omareen, co-author of a new anthology of writing and art about the Syrian tragedy, watched a video of the protest he knew it was a “watershed moment.”

“The barriers of fear were collapsing,” he wrote. “And the doors of the Kingdom of Silence were flung open.”

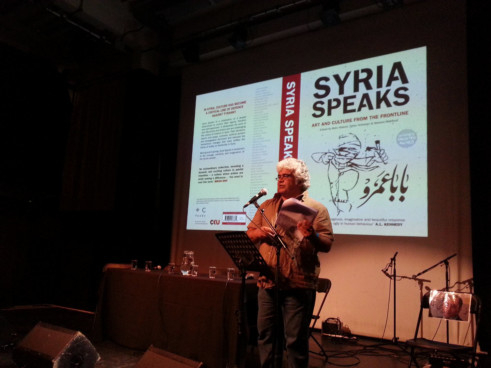

The anthology, “Syria Speaks — Art and Culture from the Frontline”, demonstrates just how wide those doors have been opened. It has brought together 50 dissident voices — writers, poets, artists, cartoonists — who, despite the threat of imprisonment, torture or death, fearlessly and graphically expose the horrors of the conflict, satirise the Syrian leadership, confront sectarianism and grapple with the understanding of what it is to be Syrian.

Before the uprising of 2011 those voices might have been silenced out of fear of a repressive government that stamped out any dissidence, but today it is as if they have been steeped in blood for so long that they feel they have nothing to lose. The barriers of fear have indeed been swept aside.

As writer and artist Khalil Younes says: “When you’re on the ground the only way is up. Three years ago people would not write like this. Absolutely not. When I talk about the Revolution or the uprising it’s not only an uprising of people against the government, but also a revolution on many levels. Before 2010 some opinions were a luxury. People were not even courageous enough to write stuff against the government. For example, if you talked about a news anchor that you didn’t like you might have ended up in prison because you don’t know who he is, or who he knows.

“The Revolution shattered these boundaries because the response at the beginning against the demonstrators by Bashar Al Assad and the army was horrific. The people were not asking for a change in the regime, they had modest demands, but the first response was the killing and shooting of people, hunting them down on the streets.

“When you start at that level then you don’t have anywhere to go. The people are not going to have anything more valuable than life to lose so, in a way, they stop being afraid because the ultimate thing that could happen to any human being happened on that first day. There is nothing worse that could happen to them.”

The result is a collection of brutal images, satirical cartoons, posters, moving memoires and powerful fiction as well as thoughtful analysis — all arguing for dignity and freedom. There is, of course, anger and outrage but the abiding effect is more of sadness, of weariness and despair. As well as a steely resolve.

On a recent tour of the UK the anthology’s editors Malu Halasa, best known for her social documentary “The Secret Life of Syrian Lingerie”, journalist Nawara Mafhoud and Zaher Omareen, explained the message of the book.

Malu Halasa says that the international media has failed to understand the nuances of the situation.

“I think is incredibly important for all of us trying to understand what is happening in Syria is to trust the people, the writers and the artists. What we have tried to show in the book is that the power of culture helps you learn about people’s lives. People speak for themselves; they are telling you what their lives are like, what they are thinking about, what they are doing and how they are reacting.”

And in the foreword to the book she elaborates: “Simply put, creativity is not only a way of surviving the violence, but of challenging it... if there is a single message in ‘Syria Speaks’, it is that meeting violence with violence is never successful. For Syrians and non-Syrians alike, there are many reasons to wake up every morning and reach for the pen, the easel, the camcorder or the laptop — instead of a gun.

As Zaher Omareen, who is also the media director of the Damascus Film Festival and a lecturer at Damascus University, says: “We have a new generation who are expressing themselves in short stories, films and social media. They are using a new style in which they want to talk about their own problems, using slang, even using dirty language, talking about their daily problems. Before 2011 literature was for an elite group of artists, writers and journalists but now we have these new platforms. Supporters of the revolution are now armed with their own instruments, which can contribute to undermining all authority.”

Some examples in the anthology rely on black humour to make their point such as the, admittedly simple, cartoons by anonymous illustrators in the hamlet of Kafranbel in north western Syria, the wry cartoons of Ali Farzat and comic strips such as “Cocktail” which tells the story of two young men on either side of the conflict, one Alawi, one Sunni, who both suffer at the hands of government enforcers.

The most overt symbols of revolution are the drawings by Sulafa Hijazi, in which she shows, for example, a hand holding worry beads made of skulls — one of her less brutal images. Kahlil Younes is similarly compelling. The depiction of a young man called Hamza Bakkour, who had the lower part of his face shot off in a bombing raid on Homs, is unsparing.

“We knew about him from Facebook,” he says. “But these images are swiftly lost because there is so much to be seen. I needed to document it to keep people aware of his story for 100 years.”

Citizen photographers have captured the destruction and a largely internet-based network of clandestine cells of similarly untrained journalists organised by Local Coordinating Committees (LCC) have made more than 300,000 videos. Bizarrely, some of the supplies — spy cams, mobiles, memory sticks, laptops, even gas masks — are bought in the Dragon Mart shopping centre in Dubai.

The book also considers the importance of citizenship. In a measured essay by Hassan Abbas on sectarianism and citizenship he argues that as Syria implodes, some people are looking beyond the disaster to a day when the nation recovers; a day when they will need to understand and embrace the true meaning of citizenship and national belonging — the need to accept the diversity of the country.

He writes: “The culture of citizenship is the impenetrable bedrock that holds together diverse societies, whether national or religious. It is a vital necessity for our societies, which are characterised by deep-rooted, mosaic structures.

“A culture of citizenship also presupposes that citizens will feel social responsibility, do what the law requires of them in terms of protecting the nation from dangers and disasters and participate in the necessary social services that contribute to the life of society as a whole. However, a culture of citizenship is distinguished above all by citizens’ respect for the law; by political participation and citizens’ exercise of their rights through voting and being elected; by the performance of military or civil service (rather than avoiding this responsibility); and by the payment of taxes.”

But what really hits home are the personal memoirs and the fiction. Renowned writer Khaled Khalifa, who still lives in Damascus and suffered a broken arm when attacked during a funeral, reflects the tension of living in the totalitarian state of the first Assad in his short story “Lettuce Fields”.

Samar Yazbeck describes a journey through the northern countryside where a young rebel leader gives her an account of an attack by the army that ends with the victorious soldiers killing an insurgent and “dancing and shouting for joy.”

“Everyone spoke with a granite-like solemnity,” she writes.

Dara Abdullah tells the story of a rebel imprisoned in a Damascus prison in “Loneliness Pampers its Victims”. At first greeted as a hero, the smell of the putrefying wound is so bad that the hero is shunned. When he dies “some were sad, some were silent and some were happy. Among those who were happy were those who welcomed him upon arrival.”

In his prose poem “I’m Positively Sure about the Event” Rasha Omran writes “of the streets that are no longer vocabularies for poems. Of the faces that abandoned their indifference about real names and pseudonyms...” and ends with a litany of anger and blood-stained despair — “blood in the air, blood in the dust, blood in the cigarettes, blood in the cheap alcohol, blood in the night”.

Khalil Younes, now based in Chicago, but brought up in a poor part of Damascus where Christian, Druse, Alawi, Sunni and Shia lived together uses that background in “Chicken Liver” in which he tells of two friends separated by time and geography — one a supporter of the Revolution in Chicago; the other fighting for the army. He describes how his friend Hassan phoned a cousin who was also in the army only to have the call answered by a rebel fighter: “The owner of the phone is dead.” he says “We killed him.”

“I still phone Hassan every couple of days,” writes Younes. “The nightmare that always haunts me, makes my hair stand on end, is that someday I might hear a strange voice instead on the other end of the line, telling me: ‘The owner of this phone is dead. We killed him.’”

Richard Holledge is a writer based in London.