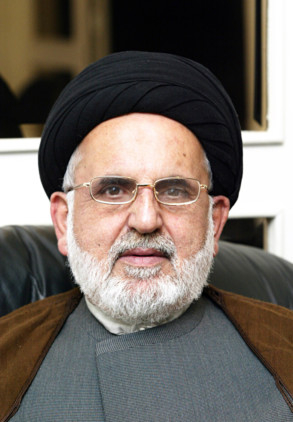

Beirut: Barely 68 and seriously ill during the past several years, Sayyed Hani Fahs passed away on Friday, plunging Lebanon in yet another dark moment.

Much like Sayyed Mousa Sadr three decades ago, this leading Shiite clergyman marked his time, and rose above sectarian prejudices to embrace humanity. His message was clear: all Lebanese are equal and must reinforce the sole legitimate state that stands above them. He recommended that the Lebanese practice what the statesman Lord Parlmerston — who served twice as Prime Minister in the mid-19th century — applied in Britain, namely to avoid “eternal” alliances, and to make no perpetual enemies. Fahs believed in the 1943 National Pact and the Ta’if Accords, even if he did not rule our evolutionary and orderly reforms, though he categorically rejected the use of violence to gain power.

Born in Jibchit, South Lebanon in 1946, Hani Fahs travelled to Najaf, Iraq, to pursue his religious education. He returned to Lebanon in 1972 with his family — five sons and two daughters — survived the civil war starting in 1975, and endured the Israeli occupation of the South between 1982 and 2000, though he briefly lived in Iran (1982-1985) when he worked at the press office of the Qom School of Theology.

An exceptional patriot and an icon of moderation who commanded wide respect both within the Shiite community as well as among Sunnis, Druzes, and Christians, Sayyed Hani advocated a cultural and religious rapprochement among the citizens of this country. He was active in several groups that encouraged intra-Lebanese and Christian-Muslim dialogues, as he also earned a position on the Shariah Council of the Higher Shiite Islamic Council.

Although he backed Hezbollah when the party organised opposition against Israeli occupation that lasted over 22 years, and long before the outbreak of the civil war in Syria — where Hani Fahs stood with the oppressed people that rejected Ba‘ath Party rule — the Sayyed disagreed with Hezbollah on key issues, including the velayat-e faqih [guardianship of the jurist] doctrine that called on all Shiites to accept Iran’s supreme leader as the highest authority on political as well as religious matters. On the contrary, Fahs believed that Shiites ought to integrate into their own societies, and never aspire to grab power for its own sake.

Consequently, the Sayyed crossed intellectual swords with Hezbollah and became an outspoken critic of the militia’s involvement in the Syrian civil war. In 2012, the learnt clergyman issued a statement along with Sayyed Muhammad Hassan Al Amin, another prominent alim, calling on Lebanon’s Shiites to switch sides and support the Syrian popular uprising.

A confident of the late Shaikh Muhammad Mahdi Shamseddine, the influential head of the Higher Shiite Council, Sayyed Fahs joined the master in esteem. Leading political and religious voices eulogised Sayyed Hani though few Hezbollah tenors expressed their regrets three days after he passed away.

An official statement from Dar Al Fatwa, Lebanon’s highest Sunni religious authority, recognised that the Shiite cleric “dedicated his life to the service of Lebanon and national unity and to boosting brotherhood ties between Muslims.”

Druze spiritual leader Shaikh Naim Hasan said that the country would miss Fahs’ uniting stances.

Samir Franjieh, a member of the March 14 General Secretariat and an intellectual voice in his own right, told the online NOW site that Fahs had been a strong supporter of the Lebanese state, declaring: “In his last speech, which he delivered at the Lady of the Mountain Gathering, Sayyed Hani Fahs concentrated on the concept of the state. He stressed that Lebanon’s only salvation was to rely on the authorities, and rejected what is happening in Syria.”

Politicians hailed Fahs’ role in Lebanon too, with Former Prime Minister Saad Hariri acknowledging the cleric’s “rich experiences,” while he praised his various positions that “will remain imprinted in our national memory.” Fahs was a “wise” man, Hariri added, and “I personally feel the magnitude of this loss since I knew Sayyed Hani in the most difficult circumstances.”

Lebanese Forces leader Samir Geagea said in mourning the erudite cleric’s death: “Lebanon has lost a scholar, thinker, a great symbol of moderation and love among the sects in Lebanon.” Geagea, one of only two declared presidential candidates, concluded that Hani Fahs was a true “man of dialogue and communication with distinction, and I will personally miss him greatly.”

Deputy Ali Khreiss, a Shiite member of parliament and part of the Amal Movement, was one of the few Shiite politicians who praised Hani Fahs. “Although we sometimes disagreed with him on political issues,” affirmed the deputy from the city of Sur, “no one can deny the great loss the passing of the scholar Hani Fahs will leave, for Muslims as well as Christians.”

Khreiss continued: “His knowledge and cultural contributions are highly regarded by the most important scholars,” and it behoved the Lebanese to recognise that the late Sayyed was a staunch believer in coexistence, saying “that there could be no homeland without both Christians and Muslims.”

Although Sayyed Fahs never reached the political station in Lebanon that Cardinal Richelieu (1585—1642) achieved in France, he nevertheless was a astute student of history, and adopted the Frenchman’s dictum: “Because man is immortal, his salvation lies in the hereafter. A state, on the other hand, has no immortality, which means that its salvation is now or never.” That’s what the gifted and gentle soul wished to see implemented in his native Lebanon though that required his countrymen to abandon ephemeral foreign alliances.