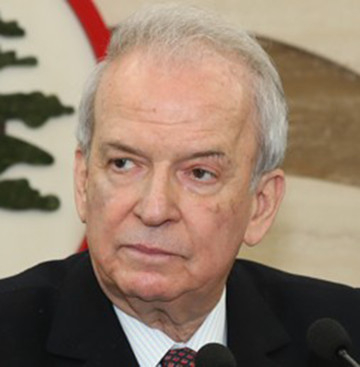

Beirut: Judge David Re, who is presiding over the UN-backed Special Tribunal for Lebanon (STL), and which is undertaking the prosecution under Lebanese criminal law of four men for the February 14, 2005 assassination of former Prime Minister Rafik Hariri and 22 others, told Marwan Hamadi that he could resume his political activities until December 3, 2014 but that he ought not discuss the content of his testimony to date with others. Hamadi jokingly said he would return to continue his presentation of evidence “unless something happens to me in Beirut.”

Hamadi was questioned by the STL that is trying Salim Jameel Ayyash, Mustafa Ameen Badr Al Deen, Hussain Hassan Oneissi and Assad Hassan Sabra — Hezbollah members who remain at large — though what the Chouf deputy and former journalist testified pertained to the role of Syria during the latter’s occupation.

On October 1, 2004, Hamadi survived one of the car bombings that targeted Lebanese politicians during the past decade, in what was the beginning of a series of assassinations of anti-Syrian figures. By his own avowal, the parliamentarian seldom contemplated that he would be summoned to testify at The Hague but what he told the Court during the past four days stood as an unabashed indictment of the Syrian regime that toyed with Lebanon at will for three long and painful decades.

On Thursday, the Druze politician affirmed that what the Syrian regime intended was to simply end Lebanon’s parliamentary democracy and transform it into a dictatorship. This goal necessitated a campaign that created an opposition movement aimed at curbing Syria’s domination, first known as the Qurnat Shahwan Gathering, which the assassinated Hariri supported as he became its champion.

Earlier, Hamadi told the Court — and Lebanese citizens interested in learning about their country’s contemporary history — that he met with Hariri at the residence of Progressive Socialist Party (PSP) chief Walid Junblatt in August 2004 upon the former premier’s return from a meeting with President Bashar Al Assad in Damascus. Hariri apparently said that the Syrians wanted to extend Lebanese President Emile Lahoud’s term in office and that they would settle for “no one else.”

“This meant Al Assad was insisting on the reelection of Lahoud for a new term,” said the lawmaker who, along with other officials who attended the meeting, was simply astonished at the brash demand.

In what was a full-fledged confirmation of a rumour that circulated among intellectual circles for years, Hamadi asserted that Al Assad threatened Hariri by saying he would “destroy Lebanon over his head,” if necessary. Even worse, according to this testimony, was Al Assad’s unabashed desire to humiliate Hariri. Hamadi told the court that ties were severed between the two leaders ahead of the latter’s assassination with Al Assad keeping Hariri standing at attention for 10 minutes during their last meeting before dismissing him, which broke protocol and human cordiality. The intention, Hamadi testified, was to “show that Lebanese officials must obey all orders from Damascus.”

Hariri and most Lebanese politicians eventually voted for the extension, and Lahoud served for a total of 9 years, in what were undistinguished terms. In response to a question by the prosecution, Hamadi declared that he and Hariri understood full well what Al Assad’s threats included — “bombings, internal strife, assassinations, revenge operations and anything that had already been in the dictionary of the Syrian regime since 1975” — which did not mince words.

On the super-sensitive UN Security Council resolution 1559, which the Syrians and Hezbollah rejected as deliberate foreign interference in Lebanon’s internal affairs, Hamadi was not specific as to whether Hariri had played a role in its adoption via his close relations with then French President Jacques Chirac.

“The international community sensed that Syria was pressuring Lebanese state institutions, instead of easing its grip on the country,” which probably motivated Paris and its allies to push for its adoption, remarked Hamadi. Security Council Resolution 1559 was adopted in September 2004 and called on “foreign forces” to withdraw from Lebanon and non-Lebanese militias to disband.

A prominent son of a Druze family that hailed from Ba‘aqlin, in the Chouf Mountains, [and the brother of Nadia Tueni, a notable author and French poet who was married to Gassan Tueni, the former UN ambassador and senior editor of the Lebanese daily Al Nahar, Gassan Tueni — whose own son, Gebran (Hamadi’s nephew) — was also assassinated in a car bombing in Beirut in December 2005], Hamadi offered a compelling testimony. Observers anticipated a heated cross-examination of the lawyer by training and holder of a doctorate in economics.