Baghdad: He is regarded as one of the most powerful militants in the world, a former Islamist preacher who evolved into a global jihad warrior now threatening to rewrite the map of the Middle East.

Yet Abu Bakr Al Baghdadi, the head of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant, remains largely a mystery, even to his followers.

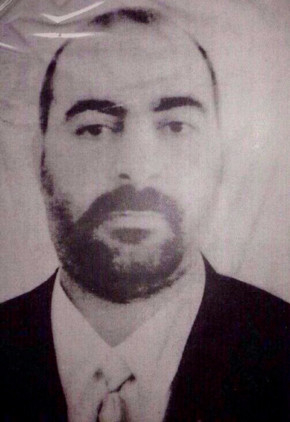

Unlike with such iconic figures as Al Qaida leaders Osama Bin Laden and Ayman Zawahiri, only two photos are known to exist of Al Baghdadi, showing a trim-bearded man with thick eyebrows. Al Baghdadi, whose fighters have seized large swaths of territory in both Syria and Iraq, releases only audio messages. Even when he meets with Isil commanders, Al Baghdadi is said not to reveal himself.

During such sessions, several men whose faces are covered to conceal their identities are said to enter the room, listen without speaking and then leave. The commanders are simply told that “one of these was Al Baghdadi, and he heard what you wanted and he will respond at a later time,” said Abu Ebrahim Raqqawi, an opposition activist in Raqqa, Syria, where Isil has established what it views as the capital of a burgeoning transnational Islamist caliphate.

“No one deals with him except leaders at the highest level,” Raqqawi said.

The emergence of Isil illustrates the growing importance of regional militant groups. Several of these have eclipsed Al Qaida’s central command, which has been battered by US drone strikes and other attacks aimed at its strongholds in Pakistan.

US officials long have worried about a group based in Yemen, Al Qaida in the Arabian Peninsula, and expressed growing concern about Al Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb, based in Algeria and Mali. The rising prominence of such regional groups, including the Al Qaida branches, has corresponded in part with internal criticism of Zawahiri as an inadequate successor to Bin Laden.

Al Baghdadi’s fighters have made brutality their calling card, executing detainees in public squares and crucifying some victims. The current fighting brings him back to familiar turf. His path was shaped by the 2003 US-led invasion of Iraq and included time in a US-run prison.

Born in Samarra, Iraq, in 1971, Al Baghdadi holds a doctorate in Islamic studies from the Islamic University in Baghdad and worked as a teacher and Sunni Muslim preacher before the invasion that toppled the Sunni-dominated government of Saddam Hussain, according to an unofficial biography that has circulated on militant web sites.

The name Al Baghdadi — his full name is Ebrahim Awwad Ebrahim Ali Al Badri Al Samarri — signifies his ties to the Iraqi capital. Al Baghdadi first fought the Americans and then the emerging Shiite-run Iraqi government as a member of the Mujahideen Army, an Islamist force with nationalistic rather than global ambitions.

“He wasn’t this globalist jihadist going to Afghanistan, but he was recruited during the Iraq war,” said Aron Lund, editor of the Carnegie Endowment’s Syria in Crisis website. “The war essentially came to him.”

Al Baghdadi is believed to have served time in the US-run prison Camp Bucca during the war, and it was there, militant sources say, that he joined a nascent Al Qaida branch known as Al Qaida in Iraq, founded by Abu Musab Zarqawi, who was killed in a 2006 US airstrike. Zarqawi led a bloody campaign of suicide bombings, kidnappings and hostage beheadings against Shiites and Americans.

In 2010, when another Islamic State of Iraq leader was slain, Al Baghdadi was elected the group’s leader.

Surviving under US occupation meant taking on a secretive existence, and Al Baghdadi continued that once he took over the helm, said Lund.

“The Islamic State of Iraq grew out of an environment when the US had agents on the ground and drones in the air, and they had nowhere to go, they had no safe areas at all,” Lund said. “And Zarqawi tried being the public leader because he was already known, but then the people who followed him were all using fake names.”

Among the thousands of fighters spread across Syria and Iraq, many of them foreigners, Al Baghdadi is now referred to as the “emir of the believers,” a title first given to the Prophet Mohammad (PBUH), said Somsam Islam, a fighter with a rival Islamist Syrian militant group, the Al Qaida-affiliated Al Nusra Front.

Isil was affiliated with Al Qaida until Al Baghdadi rebranded the franchise and went international by entering the fray in neighbouring Syria in April 2013. Introduction of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant was made in customary Al Baghdadi fashion: a 23-minute video consisting of the group’s black and white flag flapping over an audio statement.

Al Qaida chief Zawahiri unsuccessfully ordered Isil to cease operations and return to Iraq. But Al Baghdadi refused and after this somewhat inauspicious beginning, Isil forces violently seized control of large swaths of northern Syria.

Though its leader remains secretive, Isil has used social media such Twitter and YouTube to recruit seasoned and first-time Sunni fighters from around the world, including North Africans, Europeans and a large group of Chechens. These fighters have been lured by recruitment videos portraying Syria as a showdown between Sunnis on one side and Shiites and Alawites on the other.

In Syria, Isil is at odds with most other opposition groups, including militants from Al Nusra Front, as well as the government of President Bashar Al Assad.

In a January audio message after weeks of deadly clashes between Isil and other militants, Al Baghdadi tried to ease the tension. He urged his fighters to cease battling rebels who laid down their weapons “and forgive and reconcile so you fight a depraved enemy,” meaning Al Assad.

Yet if anything, Isil has managed to consolidate its territorial holdings in north-east Syria near the border with Iraq. As it seizes cities in Iraq, including Mosul and Tikrit, the hometown of Hussain, the border between the two nations has become somewhat of a fiction.

Just as he exploited power vacuums in opposition-held parts of Syria to establish a foothold, Al Baghdadi is now capitalising on sectarian politics in Baghdad and an alienated Sunni population to seize northern Iraqi territory at a stunning pace.

His success at shaping Isil has allowed him to present himself as one of the most important of a new generation of militants, rivaling Zawahiri.

A decade after Al Baghdadi was reportedly under American detention, the US, which designated him a global terrorist in 2011, is offering a $10-million reward (Dh36.7 million) for information aiding in his capture or killing. The sum is second only to that offered for Zawahiri.

Los Angeles Times