Baghdad: The face stares out from multiple billboards in central Baghdad, a grey-haired general casting a watchful eye across the Iraqi capital. This military commander is not Iraqi, though. He’s Iranian.

The posters are a recent arrival, reflecting the influence Iran now wields in Baghdad.

Iraq is a mainly Arab country. Its citizens, Shiite and Sunni Muslims alike, have long mistrusted Iran, the Persian nation to the east. But as Baghdad struggles to fight the Islamist extremist group Daesh, many Shiite Iraqis now look to Iran, a Shiite theocracy, as their main ally.

In particular, Iraqi Shiites have grown to trust the powerful Iranian-backed militias that have taken charge since the Iraqi army deserted en masse last summer. Dozens of paramilitary groups have united under a secretive branch of the Iraqi government called the Popular Mobilisation Committee, or Hashid Shaabi. Created by Prime Minister Haider Al Abadi’s predecessor Nouri Al Maliki, the official body now takes the lead role in many of Iraq’s security operations. From its position at the nexus between Tehran, the Iraqi government, and the militias, it is increasingly influential in determining the country’s future.

Until now, little has been known about the body. But in a series of interviews with Reuters, key Iraqi figures inside Hashid Shaabi have detailed the ways the paramilitary groups, Baghdad and Iran collaborate, and the role Iranian advisers play both inside the group and on the front lines.

Those who spoke to Reuters include two senior figures in the Badr Organisation, perhaps the single most powerful Shiite paramilitary group, and the commander of a relatively new militia called Saraya Al Khorasani.

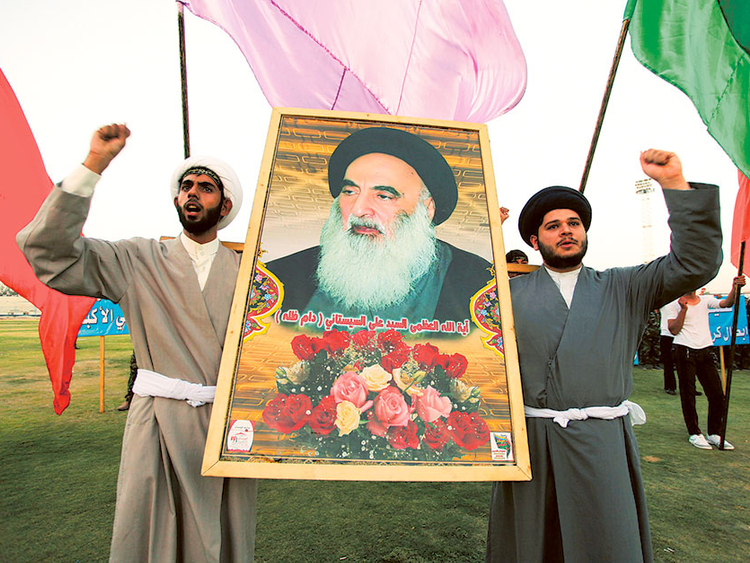

In all, Hashid Shaabi oversees and coordinates several dozen factions. The insiders say most of the groups followed a call to arms by Iraq’s leading Shiite cleric Grand Ayatollah Ali Al Sistani. But they also cite the religious guidance of Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, the supreme leader of Iran, as a key factor in their decision to fight and — as they see it — defend Iraq.

Hadi Al Amiri, the leader of the Badr Organisation, told Reuters: “The majority of us believe that ... Khamenei has all the qualifications as an Islamic leader. He is the leader not only for Iranians but the Islamic nation. I believe so and I take pride in it.” He insisted there was no conflict between his role as an Iraqi political and military leader and his fealty to Khamenei.

“Khamenei would place the interests of the Iraqi people above all else,” Amiri said.

Hashid Shaabi is headed by Jamal Jaafar Mohammad, better known by his nom de guerre Abu Mahdi Al Muhandis, a former Badr commander who once plotted against Saddam Hussein and whom American officials have accused of bombing the US embassy in Kuwait in 1983.

Iraqi officials say Muhandis is the right-hand man of Qassem Sulaimani, head of the Quds Force, part of Iran’s Revolutionary Guard. Muhandis is praised by some militia fighters as “the commander of all troops” whose “word is like a sword above all groups.” The body he heads helps coordinate everything from logistics to military operations against Daesh. Its members say Muhandis’ close friendships with both Sulaimani and Amiri helps anchor the collaboration.

The men have known each other for more than 20 years, according to Muen Al Kadhimi, a Badr Organisation leader in western Baghdad. “If we look at this history,” Kadhimi said, “it helped significantly in organising the Hashid Shaabi and creating a force that achieved a victory that 250,000 (Iraqi) soldiers and 600,000 interior ministry police failed to do.” Kadhimi said the main leadership team usually consulted for three to four weeks before major military campaigns. “We look at the battle from all directions, from first determining the field ... how to distribute assignments within the Hashid Shaabi battalions, consult battalion commanders and the logistics,” he said.

Sulaimani, he said, “participates in the operation command centre from the start of the battle to the end, and the last thing (he) does is visit the battle’s wounded in the hospital.” Iraqi and Kurdish officials put the number of Iranian advisers in Iraq between 100 and several hundred — fewer than the nearly 3,000 American officers training Iraqi forces. In many ways, though, the Iranians are a far more influential force.

Iraqi officials say Tehran’s involvement is driven by its belief that Daesh is an immediate danger to Shiite religious shrines not just in Iraq but also in Iran. Shrines in both nations, but especially in Iraq, rank among the sect’s most sacred.

The Iranians, the Iraqi officials say, helped organise the Shiite volunteers and militia forces after Grand Ayatollah Sistani called on Iraqis to defend their country days after Daesh seized control of the northern city of Mosul last June.

Prime Minister Al Abadi has said Iran has provided Iraqi forces and militia volunteers with weapons and ammunition from the first days of the war with Daesh.

They have also provided troops. Several Kurdish officials said that when Daesh fighters pushed close to the Iraq-Iran border in late summer, Iran dispatched artillery units to Iraq to fight them. Farid Asarsad, a senior official from the semi-autonomous Iraqi region of Kurdistan, said Iranian troops often work with Iraqi forces. In northern Iraq, Kurdish Peshmerga soldiers “dealt with the technical issues like identifying targets in battle, but the launching of rockets and artillery — the Iranians were the ones who did that.” Kadhimi, the senior Badr official, said Iranian advisers in Iraq have helped with everything from tactics to providing paramilitary groups with drone and signals capabilities, including electronic surveillance and radio communications.

“The US stayed all these years with the Iraqi army and never taught them to use drones or how to operate a very sophisticated communication network, or how to intercept the enemy’s communication,” he said. “The Hashid Shaabi, with the help of (Iranian) advisers, now knows how to operate and manufacture drones.”

One of the Shiite militia groups that best shows Iran’s influence in Iraq is Saraya Al Khorasani. It was formed in 2013 in response to Khamenei’s call to fight Islamist militants, initially in Syria and later Iraq.

The group is responsible for the Baghdad billboards that feature Iranian General Hamid Taghavi, a member of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard. Known to militia members as Abu Mariam, Taghavi was killed in northern Iraq in December. He has become a hero for many of Iraq’s Shiite fighters.

Taghavi “was an expert at guerrilla war,” said Ali Al Yasiri, the commander of Saraya Al Khorasani. “People looked at him as magical.” In a video posted online by the Khorasani group soon after Taghavi’s death, the Iranian general squats on the battlefield, giving orders as bullets snap overhead. Around him, young Iraqi fighters with AK-47s press themselves tightly against the ground. The general wears rumpled fatigues and has a calm, grandfatherly demeanour. Later in the video, he rallies his fighters, encouraging them to run forward to attack positions.

Within two days of Mosul’s fall on June 10 last year, Taghavi, a member of Iran’s minority Arab population, travelled to Iraq with members of Iran’s regular military and the Revolutionary Guard. Soon, he was helping map out a way to outflank Daesh outside Balad, 80km north of Baghdad.

Taghavi’s time with Saraya Al Khorasani proved a boon for the group. Its numbers swelled from 1,500 to 3,000. It now boasts artillery, heavy machine guns, and 23 military Humvees, many of them captured from Daesh.

“Of course, they are good,” Yasiri said with a grin. “They are American made.” In November, Taghavi was back in Iraq for a Shiite militia offensive near the Iranian border. Yasiri said Taghavi formulated a plan to “encircle and besiege” Daesh in the towns of Jalawala and Saadiya. After success with that, he began to plot the next battle. Yasiri urged him to be more cautious, but Taghavi was killed by a sniper in December.

At Taghavi’s funeral, the head of Iran’s Supreme National Security Council, Ali Shamkhani, eulogised the slain commander.

He was, said Shamkhani, one of those Iranians in Iraq “defending Samarra and giving their blood so we don’t have to give our blood in Tehran.” Both Sulaimani and the Badr Organisation’s Amiri were among the mourners.

Saraya Al Khorasani’s headquarters sit in eastern Baghdad, inside an exclusive government complex that houses ministers and members of parliament. Giant pictures of Taghavi and other slain Al Khorasani fighters hang from the exterior walls of the group’s villa.

Commander Yasiri walks with a cane after he was wounded in his left leg during a battle in eastern Diyala in November. On his desk sits a small framed drawing of Iran’s Khamenei.

He describes Saraya Al Khorasani, along with Badr and several other groups, as “the soul” of Iraq’s Hashid Shaabi committee.

Not everyone agrees. A senior Shiite official in the Iraqi government took a more critical view, saying Saraya Al Khorasani and the other militias were tools of Tehran. “They are an Iranian-made group that was established by Taghavi. Because of their close ties with Iranians for weapons and ammunition, they are so effective,” the official said.

Asarsad, the senior Kurdish official, predicts Iraq’s Shiite militias will evolve into a permanent force that resembles the Iranian Revolutionary Guard. That sectarian force, he believes, will one day operate in tandem with Iraq’s regular military.

“There will be two armies in Iraq,” he said.

That could have big implications for the country’s future.

Human rights groups have accused the Shiite militias of displacing and killing Sunnis in areas they liberate — a charge the paramilitary commanders vigorously deny. The militias blame any excesses on locals and accuse Sunni politicians of spreading rumours to sully the name of Hashid Shaabi.

The senior Shiite official critical of Saraya Al Khorasani said the militia groups, which have the freedom to operate without directly consulting the army or the prime minister, could yet undermine Iraq’s stability. The official described Badr as by far the most powerful force in the country, even stronger than Prime Minister Al Abadi.

Amiri, the Badr leader, rejected such claims. He said he presents his military plans directly to Al Abadi for approval.

His deputy Kadhimi was in no doubt, though, that the Hashid Shaabi was more powerful than the Iraqi military.

“A Hashid Shaabi (soldier) sees his commander ... or Haji Hadi Amiri or Haji Muhandis or even Haji Qassem Sulaimani in the battle, eating with them, sitting with them on the ground, joking with them. This is why they are ready to fight,” said Kadhimi. “This is why it is an invincible force.”