Yousuf Ahmad Mohammad and Samah Al Saud

DATE MOHAMMAD LEFT SYRIA: June 2013

HOMETOWN IN SYRIA: Khirbet Ghazaleh

CURRENTLY: Zaatari refugee camp, Jordan

Yousuf Ahmad Mohammad saw her in the market, a rare breath of beauty amid the misery of refugee life.

Someone said she was from his village back in Syria, which he fled four months earlier when a Syrian government plane dropped bombs that destroyed his home. But he had never seen her before, so he asked his mother to investigate.

Now, two months later, here he is, a groom, a skinny 23-year-old dressed in a black suit and a purple tie. He is knocking on the rusty metal door of his bride’s home, a cinder-block building that used to be a public latrine, where the beauty from the market is primping for her wedding.

It is a moment of renewal and resilience amid the sadness and loss. They have settled into life in a foreign land, in a crowded, dirty camp that could be their home for years. But the rhythms of life go on.

On a hot afternoon, Samah Al Saud, 24, emerges in a white satin dress, fully veiled with a tall hood covering her head. Music is blaring from a portable loudspeaker, and her girlfriends who helped her get ready start dancing in the dirt streets.

Dozens of friends and neighbours crowd in close as she and her groom step into an old blue Opel taxi, the only car amid all the refugee tents and trailers. It has come to carry them to their new life.

Bride and groom squeeze into the back seat with the bride’s mother. The groom’s mother sits up front with the taxi driver, and at least four children pile in for the ride. The taxi driver honks the old car’s horn in celebration, but it sounds like the weak bleat of a mildly annoyed sheep. The car pulls out down the roadway, rolling through filthy, trash-filled puddles.

It’s tradition to have a small convoy of cars accompany the bride and groom to their wedding. But here in Zaatari, the old taxi is the only car available, and a crowd of teenage boys running alongside is its only escort.

The car reaches the camp’s main drag, known as the Champs-Elysees, where the necessities and luxuries of camp life are for sale: propane stoves, vegetables, television sets.

A few people stop to wave at the passing wedding party, which arrives 15 minutes later at the groom’s family house - a couple of metal trailers, with a UN tent stretched between them to make a small, shady courtyard.

Music is blasting as bride and groom step out of the taxi. Young men dance in the dirt, next to open pits filled with trash, kicking up rocks and dust with their joyous steps. The bride and groom greet everyone, then men and women separate for a meal of chicken and rice.

No religious or civil authority formally seals the pair. Their wedding is part of a rising trend of unofficial weddings among refugees in which the two families simply get an elder to agree that the wedding is proper. That saves money, time and paperwork, but the wedding is not officially recognised.

None of that matters to Mohammad.

“I am happy to be married,” he says, sitting with his brothers and male friends. They are all in jeans and T-shirts; bride and groom are the only ones who are dressed up.

“But real happiness will come when I go back to my country,” he says. “This is my temporary home, and it is fine. But I will only be happy in my village.”

He says he and his bride will hold off on children, at least for now.

“I don’t want to bring children into this life,” he says. “It’s better to die without children in Syria than it is to bring children into the world as refugees. How can you build a life on a foundation like this?”

Mohammad says he would like to go fight in Syria, as so many other young men from Zaatari do, but he says his family needs him here.

As he sits in his trailer, the wedding party winding down, Mohammad sips coffee and remarks that despite the monotony and hopelessness of refugee life, he feels lucky to have met his bride here.

“Thank God, something good came out of something bad,” he says.

By 5 o’clock, the party is over.

Abdul Rahman Ahmad

DATE HE LEFT SYRIA: January 2013

HOMETOWN IN SYRIA: Elmah

CURRENTLY: Zaatari refugee camp, Jordan

Abdul Rahman Ahmad is 105 years old.

He was born into the Ottoman Empire. He hasn’t had teeth for 42 years.

“My wife took them out with her kisses,” he says.

By his count, Ahmad has had six wives, nine children, more than 100 grandchildren and at least 150 great-grandchildren.

“After that I’m not sure - I don’t keep in touch with them all,” he says, laughing. He’s always laughing, his rheumy, cataract-clouded eyes twinkling with mischief.

He lived for most of his life in the Syrian village of Elmah, where he was a farmhand tending wheat, lentils, chickpeas and watermelons.

Then the Syrian war came, and his house was destroyed by bombs dropped by Syrian government planes. Now he lives in a 20-foot-long trailer among 120,000 other Syrians crammed into the sprawling chaos of the Zaatari refugee camp in the desert of northern Jordan.

Most elderly refugees worry about doctors and healthcare and spend a lot of time at the camp’s numerous medical clinics. Not Ahmad. He feels great. He says he has never been to a doctor in his life.

He doesn’t take medicine. Won’t even take an aspirin.

“God will take care of me,” he says.

He says he has perfect eyesight - doesn’t even need reading glasses. But that’s not a big problem since he never went to school and never learned to read or write. His village didn’t even have a school until 1930.

He eats a lot of hard candy. He loves coffee and drinks buckets of the high-octane, mud-thick brew that is coffee in this part of the world.

His white beard is stained yellow at the centre of his upper lip, from the cigarettes he is constantly puffing. He says he smokes three packs a day, and there is always a pack of Manchester Lights sitting in front of him on the foam pad on the floor where he spends his days and nights, wrapped up in gray blankets.

The secret of his longevity?

“The keys to a long life are cracked wheat, olive oil, tobacco and God,” he says, with the dead certainty of a man who has lived a century, his face almost disappearing in a cloud of cigarette smoke.

About the only concession Ahmad makes to old age is his wheelchair, which he uses to get around the rutted dirt roads of the refugee camp. He likes to walk a few steps every evening for exercise.

He mainly passes the time with family and neighbours, who seem to love to crowd around him. He’s fun. He’s a smart aleck. He says his final dream in life is to travel to Venezuela.

Why Venezuela? His friends practically shout at him as they ask, since he doesn’t hear so well.

“For the weather and the women,” he says, and everyone roars.

But there is a serious side, too. Ahmad is sad about being forced from his home.

“When you leave your country it’s hard,” he says. “It’s OK here, but I lived in Syria for 104 years. My whole life in the same village. But if I have to die in Jordan, I will die in Jordan.”

He keeps up on the news from Syria through his friends.

“The crisis is getting worse and worse,” he says. “Right now I’d like to pick up a gun and go join the Free Syrian Army.”

Asked whether he knows the name of the US president, he shakes his head and says, “Why would I know that?” (There have been 19 in his lifetime.) But when prompted by his friends, a look of recognition spreads across his face.

“Yes, Obama,” he says. “I want him to come save us.”

Fathiya Ahmad and her family

DATE THEY LEFT SYRIA: January 2013

HOMETOWN IN SYRIA: Aleppo

CURRENTLY: Gaziantep, Turkey

It’s a big rat, a couple of pounds of long-haired nastiness. He darts between a few rocks next to where Fathiya Ahmad’s grandchildren are playing. The kids squeal with delight and use sticks to prod him into the open. To them he’s not exactly a pet, but certainly a bit of entertainment.

Rats, heat, rain, mud, hunger. It’s what Fathiya’s new life looks like in Gaziantep, an industrial Turkish city near the Syrian border. She and 17 other people live in a tiny compound in a slum that bakes in the heat and floods in the rain.

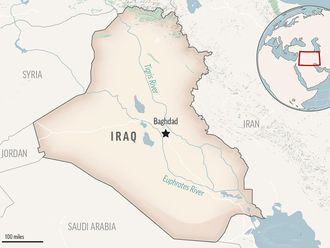

About a quarter of the 2.3 million people who have fled Syria live in refugee camps. The rest have sought shelter wherever they can find it in Turkey, Jordan, Lebanon, Iraq and Egypt. For those with money, that means a decent apartment. But many more, like Fathiya and her family, live in crowded misery in swelling urban slums.

“We feel sad that we have to live like this,” says Fathiya, 45, who sleeps, cooks and bathes in a bare, 12-by-12-foot room with four daughters and two sons. “We left our house behind. We left our life. Whatever it was, it was better than here.”

Back in Aleppo, before the war, life was not great, but at least it was clean and safe. Fathiya’s husband was a taxi driver, and he earned enough to support the family and buy a decent apartment.

Then in January, one of President Bashar Assad’s planes dropped a bomb that exploded close to their house. A piece of shrapnel hit Fathiya’s husband in the head and killed him instantly.

The family buried him in Aleppo, then decided to join the exodus of nearly 700,000 Syrians who have fled to Turkey. They left in a huge group - Fathiya and all six of her children, who range in age from 7 to 30, plus two grandchildren. They hitched a ride in the back of a truck to a village in the countryside, then walked the final hour to the border.

They crossed over, and she says they have been living ever since on the kindness of Turks - including a “nice Turkish lady” who allowed them to move into their little compound rent-free.

The place has four cinder-block rooms with tile and tin roofs with gaping holes, set around a courtyard of dirt and gravel. Clothes hang from lines everywhere, and blankets air out in the afternoon sunshine. They have no chairs. Everyone sits on the ground or on a rock.

Fathiya cooks on a tiny blue propane stove, and a city truck comes twice a week to fill their two big plastic tanks for drinking water. They keep all their food in jars, or in plastic bags hung from the ceiling rafters to keep the rats away.

Everyone shares one outhouse, a simple pit in the ground.

Their only income is what her sons earn when they can find day labour loading bricks onto a truck. It pays about $10 (Dh36.70) a day. Mostly, Fathiya says, they survive on donations from Turkish strangers who stop by with bags of clothes or food. One person even donated a satellite dish so the children could watch TV.

“We need to go back to our home country. But we have to be sure it is really safe,” says Fathiya, who heard that her house was destroyed by a bomb after they left. “I think it will take five or six years before the fighting ends. If we go there now, we will go to our death.”

Fathiya and the other women in the compound are in constant motion, tending to big sheets of clear plastic laid out on the ground, covered with a bright red, soupy tomato mush.

They are making tomato paste, their dinner staple. A neighbourhood grocer gives them his tomatoes that are too rotten to sell. Ahmad and the other women smash them into a puree and lay it out to dry. That usually takes about 10 days - longer if it rains.

Ahmad is constantly scooping water from the mush with her hand or a spoon.

The children laugh as they spot the rat again - now he’s over by the propane stove.

At least, Ahmad says, the rats don’t bother with her tomato paste.

It’s too sour for them.

Mohammad and Ahmad Al Khalid

DATE THEIR FAMILY LEFT SYRIA: March 2012

HOMETOWN IN SYRIA: Homs

CURRENTLY: Balamand, Lebanon

Ahmad Al Khalid lost his left eye to cancer before his first birthday.

He’s now nearly 2, and his mother is terrified that he is going to lose the other one.

They are Syrian refugees, forced to flee when their government’s planes dropped bombs on their house in Homs a year and a half ago. Now they live in a half-finished shopping mall in northern Lebanon, along with 1,000 other refugees who have sought shelter in shops that were built for selling clothes and shoes.

They are living on the generosity of the Lebanese government, plus the United Nations and private aid groups.

But UN and Lebanese officials, swamped with about a million refugees in a country with a population of 4.4 million, say they cannot afford to provide free health care for every sick refugee.

So Ahmad’s mother squeezes her baby tight and feels helpless.

Ahmad was 3 months old when a Syrian doctor diagnosed cancer, removed his left eye and replaced it with a prosthetic.

Around the same time, the family was forced to flee to Lebanon, where doctors said the boy needed chemotherapy. The cancer was in both eyes, and he would lose his right eye as well if he did not get treatment.

His mother says Lebanese doctors told her the chemotherapy would cost about $11,000 (Dh40,000) - an impossible sum. So she decided to take her chances with the war in Syria and take Ahmad to Damascus, where his treatment would be fully covered.

Ironically, the same government that bombed their home still provides free health care - although many doctors have fled, nearly 40 per cent of Syrian hospitals have been destroyed and drugs are increasingly scarce.

Abeer, Ahmad’s mother, declines to give her last name, fearing that Syrian President Bashar Assad’s government could take retribution against her or her children during one of their medical visits to Syria.

Abeer made several trips to Damascus, sleeping in the hospital with Ahmad while he went through the chemotherapy. She says the trips were dangerous, but she didn’t see any other option. Without treatment, the cancer would have spread and killed Ahmad.

“I would do anything for my children,” she says.

Doctors in Lebanon say Ahmad has been stable for several months, but he is still getting regular laser treatments in Beirut for his right eye. Abeer says those treatments cost $66 each, which is being paid by a Lebanese charitable organisation.

But she says just getting to the hospital, more than an hour’s drive away, is an expense she can barely afford. Ahmad’s father has a job helping to clean the abandoned shopping mall where they live. He is supposed to be paid about $260 a month. But that comes mainly from contributions from other refugees, who often can’t pay.

Even when he is paid, rent for their room is $225 a month, which leaves less than $40 for everything else. They receive help from the UNHCR and the Lebanese charity that helps with medical bills, but they are still short every month.

Ahmad is being treated at the American University of Beirut Medical Centre, a highly respected private hospital.

Gassan Skaf, the hospital’s chief of neurosurgery, says that, in theory, most of the refugees’ medical bills are covered by the UN refugee agency, and the rest by private aid groups. But in practice, he says, the system is so swamped that bills go unpaid and the hospital covers the difference.

“Without major international support, I don’t think anybody could withstand this,” Skaf says. “We can do it for a month or two, but we can’t do it for years.”

UN officials say they try to meet the full demand, but the huge number of refugees makes it difficult.

Now Ahmad’s older brother, Mohammad, who is almost 4, is battling eye cancer, too. Doctors tell them it is not unusual for siblings to have the disease.

Abeer says Mohammad is also getting laser treatments paid for by the same Lebanese charity group. He has a patch over his stronger eye, which doctors say helps strengthen the weaker one. He wears a pair of blue plastic glasses that the doctor gave him.

Of the hundreds of kids playing in the shopping centre, Mohammad is the only one wearing glasses. They are a luxury that refugees can’t afford.

Mouneer Kalthoum

DATE HE LEFT SYRIA: January 2013

HOMETOWN IN SYRIA: Aleppo

CURRENTLY: Istanbul

Mouneer Kalthoum sits at a sewing machine in a basement workshop, stitching together pieces of green fabric decorated with Minnie Mouse. Eleven hours a day, he and 20 other Syrian refugees push acres of cloth through the clattering machines.

Until the government of Syrian President Bashar Assad bombed and destroyed his house in Aleppo, Kalthoum was a general contractor who built schools and hospitals. He employed 80 people and brought home about $60,000 a year.

Now Kalthoum earns $350 a month - and he pays $300 of that in rent for the three-room apartment he and his wife and four children share with his sister’s family - 11 people total.

He is 34, but his sideburns and his hair are tinged with grey. “After two years of this, I look older,” he says with a weak smile, pulling on a cigarette.

Most of the nearly 700,000 Syrian refugees living in Turkey are clustered along the border. But more than two years into the war, the refugees are increasingly spreading out. Thousands have settled into the sprawl of Istanbul, more than 700 miles from the border.

Kalthoum arrived in January. Because of heavy fighting, he and his family were forced to flee their home in Aleppo more than a year ago. They moved to a small village where his wife’s father lives. Then the government shelled that village late last year and they were forced to move again.

His wife was eight months pregnant, so she and their three children went to stay with other relatives in Latakia, a Syrian city with a good hospital.

Kalthoum went ahead to Turkey to try to build the family a new life. He hitched a ride to the border in a car with rebel fighters, then made the 15-hour bus ride to Istanbul.

He had about $2,000 in cash in his pocket, but the rest of his money is stuck in a bank account that he cannot reach. He said he had about $40,000 invested in projects that he was working on, but it is all gone.

“It’s true I lost everything, but I can compensate by hard work,” he says. “I came here for my children’s future. I started from zero, and I can start again from zero.”

Mohammad Abboud gave him the chance. Abboud works for a wealthy Syrian businessman who owns the workshop where Kalthoum sews, as well as two others in the same neighbourhood that employ dozens of Syrian men.

Abboud says Kalthoum’s shop produces 10,000 pieces of clothing a month that are exported to Egypt, Iraq, Tunisia and Morocco. He says Turkish workers are generally paid more than twice what the Syrians earn.

That has led to complaints that Syrian workers are taking Turkish jobs, as well as fears that Syrians are being exploited. Abboud says his boss is merely trying to offer Syrian refugees a fresh start.

“We want to show the Turks that we are here not just to take their money but to work,” Abboud says. “We are producers, not consumers.”

The workshop is on a side street in a quiet Istanbul neighbourhood that is filled with Syrians. Children speak Arabic as they kick soccer balls around in the street.

Down a long flight of concrete stairs, 14 sewing machines fill a basement room with whitewashed walls. Fluorescent lights hang by long wires from the high ceilings. A few couches are scattered in one corner, where some of the workers sleep.

A huge central table is covered with bundles of cotton cloth and fleece. Syrian pop music blasts from a boombox, and a few paintings of cheerful landscapes hang slightly askew on the walls. Everyone smokes.

Many of the Syrian men who work here have university degrees and had prosperous jobs in Syria. Kalthoum studied electrical engineering in school.

“My life doesn’t exist anymore,” he says. “My future is lost, but I am worried about my children’s future. I feel like I can do nothing for them.”

Khalid Nedhal Al Saawdeh

DATE HIS PARENTS LEFT SYRIA: May 2013

PARENTS’ HOMETOWN IN SYRIA: Al Nawa

CURRENTLY: Zaatari refugee camp, Jordan

At 12.45pm on a hot Monday afternoon, Hanana Assad, 32, walks slowly into a maternity clinic run by the United Nations. Her water broke last night. She hasn’t slept. Her tired eyes are framed by dark circles.

In the heavy midday heat, she has just walked almost a mile to get here from the UN-supplied trailer she shares with her six children and 20 other family members in this refugee camp of 120,000 people.

She grimaces as she tries to get comfortable on an examining table in a trailer that serves as the waiting room. The maternity clinic is four trailers - plain white boxes with a couple of windows, set around a dirt courtyard.

She is worried about the baby. She had six others back in Syria, but this is her first birth as a refugee, and it has been the hardest pregnancy. Her diet at home was rich with fruits and vegetables, but here it is mainly rice and lentils. The baby is coming three weeks early, and she blames herself - she’s stressed out, badly nourished, exhausted, scared, weak.

“I was afraid I was going to lose this one because of the stress of the bombs and the shooting and coming here from Syria,” she says.

She says her family fled their Syrian village, Al Nawa, five months ago to escape the daily bombings by Syrian government planes. They hitched a ride in a truck for 30 miles, then walked the last mile to the border. Jordanian soldiers met them and brought them to the camp.

As they were trying to get settled in the new tent home, they got terrible news. Her husband’s uncle, Khalid, who was his closest friend, had been killed by the security forces back home.

So now, Assad and her husband are praying for a boy. They will name him for their fallen relative.

Outside, the cloudless sky is blue-white, and so full of sand that it looks almost bleached. On the road just behind the trailer, hundreds of refugees push wheelbarrows full of stuff, carry plastic bags or just walk hand in hand.

“I didn’t expect to give birth here,” Assad says quietly. “I thought I’d be here for maybe two months. But here I am about to give birth to a Jordanian Syrian.”

Several thousand babies have been born at Zaatari - an average of about a dozen per day, camp doctors say - since the camp opened in July 2012.

At 1.25pm, the nurses and midwives tending to Assad decide that she is ready and move her into the delivery room. It is spartan but clean, with two delivery chairs side by side.

Twenty minutes later, the hot afternoon stillness is interrupted by a single loud scream.

The doctor, a Jordanian who works for the United Nations, delivers the baby.

“It’s a boy,” he tells Assad.

And for the first time since she arrived here, she smiles.

She has her Khalid.

The nurses clean up the baby and slip him into a little white onesie decorated with stars and planets, wrap him in a fuzzy brown blanket and hand him to his mother. They both fall asleep.

At 3.50pm, two hours after Khalid’s birth, his father arrives. Nedhal Fawad Al Saawdeh, 37, has been working all day.

He describes how his uncle Khalid was taken away by the security forces of Syrian President Bashar Assad. He says they tortured him to death in a jail cell.

“When he was taken away, I felt that part of my heart was taken away,” he says. “Today, I feel it has been returned.”

At 6pm, doctors examine mother and baby and decide they are ready to go home. They need the space; four other women have arrived since the baby was born, all about to deliver.

The clinic’s ambulance is not being used right now, so they give Assad and her husband a lift. Five minutes later, they arrive at their home, two trailers set among thousands of identical ones, set in a vast flat field of baked nothing.

A mob of children squeal with delight as Assad steps down from the ambulance, walks through the tent flap and into her trailer. She sits gingerly on a foam mat on the nearly empty floor and tries to get comfortable with her new baby.

It is dark outside now. The evening call to prayer echoes from loudspeakers across the camp outside.

Baby Khalid, named for a victim of war, born a refugee in a country that is not his own, has arrived home.