Dubai: UAE State Minister for Foreign Affairs Anwar Gargash on Sunday posted a link to a report stating that US Security and Counter-terrorism official “always knew Qatar was trouble.”

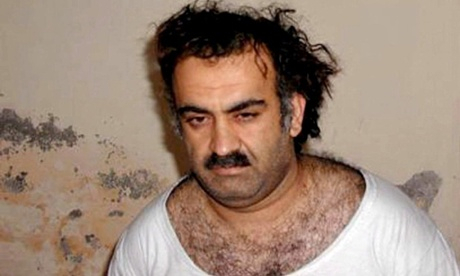

The article published by the New York Daily News on Thursday highlighted how the US authorities were unable to intercept Khalid Shaikh Mohammad, the mastermind of the 9/11 terror attacks, after authorities in Qatar where he had been living helped him escape and avoid being caught by the Americans five years before the tragic events that shook the world to the core.

“Had the Qataris handed him over to us as requested in 1996, the world might have been a very different place,” Richard Clarke, the National Coordinator for Security and Counter-terrorism in the Clinton and Bush (43) administrations, wrote in his article.

“It has been true that Qatar has served as a sanctuary for leaders of groups that the U.S. or other countries deem to be terrorist organizations. That, however, is nothing new. It has been going on for at least 20 years — and one of those who had sanctuary was the mastermind of the 9-11 attacks.

“Most people associate the name of Osama Bin Laden with the mass murders of 9/11, but another man, a serial terrorist, was the real ringleader. I first learned his name, Khalid Shaikh Muhammad (KSM), in 1993 as someone connected to the truck bomb attack on the World Trade Center. We later learned that he had an unparalleled ability to organize large-scale terrorist attacks, something bin Laden lacked.

“After the New York attack, he re-appeared in Manila in 1995 when he was implicated in the so-called Bojinka plot to bomb U.S. airliners in the Pacific.

By 1996, because of the New York and Manila plots, we considered him the most dangerous individual terrorist al large. Later that year there was a sealed federal criminal indictment for KSM. US intelligence was trying to locate him as a matter of high priority.

They found him in Qatar, where he had been given a patronage job in the Water Department. The decision about what to do next came to an interagency committee I chaired, the Counter-terrorism Security Group (CSG).”

Clarke added there was a consensus in the group that they could not trust the Qatar government sufficiently to do what otherwise would have been obvious: ask the local security service to arrest him and hand him over.

“The Qataris had a history of terrorist sympathies and one cabinet member in particular, a member of the royal family, seemed to have ties to groups like al Qaeda and appeared to have sponsored KSM.

“We decided, therefore, to do an ‘extraordinary rendition,’ a snatch by a US team, followed immediately by an exfiltration to the US In those days, the targets of extraordinary renditions were given Miranda warnings, court-appointed lawyers and jury trials in civilian courts. The problem in this case was that no US agency thought it could successfully pull off such a snatch.”

“The US embassy in Qatar was then a part of something called the ‘Special Embassy Program,” meaning that it was little more than a small State Department office.

There was no FBI liaison office in the embassy, no defense attaché, no CIA station. Neither FBI nor CIA thought they could quietly infiltrate a team without arousing the suspicions of the Qatar security services, Clarke said.

“Although Delta Force had been created to do hostage rescue and snatches in unfriendly environments, the experts in such things at the Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC) were not tasked by the Pentagon.

“Instead, the staff of the Joint Chiefs developed a military operation that had similarities to the Allied invasion of Normandy, involving thousands of U.S. military personnel off shore, in the air above, and on the ground in Qatar. It was the military leadership’s passive-aggressive way of saying that they did not want to be involved in violating a nation’s sovereign territory to grab one man that those of us in the CSG thought was a problem.

“Faced with an FBI, CIA, and Department of Defense that claimed to be incapable of snatching KSM in Qatar, or doing so only in a way likely to have appeared as an invasion, the Clinton Administration was left with only one option: approaching the Qataris. To mitigate the risk inherent in that move, the US ambassador was asked to talk only to the Emir. He would ask the Emir to talk only to the head of the Qatari security service. The request was that they should grab KSM and hold him for a few hours until we could land an arrest team to fly him to the US,” Clarke said.

“Within hours of the US ambassador’s meeting with the Emir, KSM had gone to ground. In tiny Doha, no one was able to find him. Later, the Qataris told us that they believe he had left the country. They never told us how.

KSM went on to organize the 9/11 attacks, the Bali bombing in Indonesia, the murder of US journalist Daniel Pearl, and other terrorist attacks. In 2003, he was apprehended in Pakistan by US officials accompanied by Pakistani officers. He is today in Guantanamo, Cuba, in the troubled US military court system.”