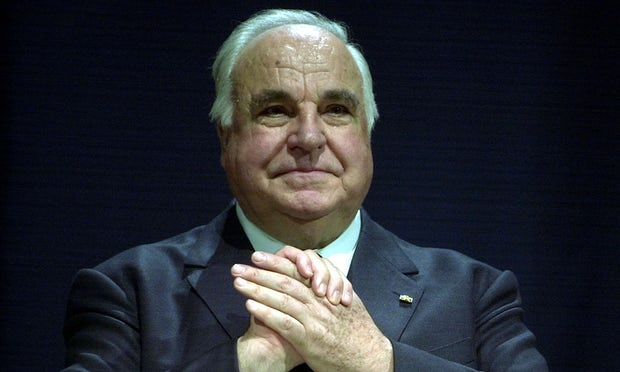

Helmut Kohl, the German chancellor who oversaw his country’s 1990 reunification after the Cold War, helped forge Europe’s economic and monetary union and gave incumbent Angela Merkel her first cabinet post, has died. He was 87.

Kohl died at his home in Ludwigshafen early Friday, Bild newspaper said on its website. The Christian Democratic Union party he used to head confirmed his death, and said in a tweet “We are in mourning.”

Germany’s longest-serving chancellor since 19th-century leader Otto von Bismarck, Kohl began his tenure in 1982 when the Soviet Union under Leonid Brezhnev still held an iron grip over eastern Europe. He was voted out of office 16 years later, having earned the title of unity chancellor after mass protests forced East Germany’s communist regime from power, leading to national reunification 11 months later.

East Germany’s collapse paved the way to power for Merkel, who broke with Kohl over a party financing scandal that erupted after he left office and soon took over his post as CDU leader. She’s now been chancellor for almost 12 years.

Kohl was aided in reuniting East and West Germany by political alliances with two U.S. presidents -- Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush -- and then-Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev. Kohl’s friendship with French President Francois Mitterrand helped pave the way for the European Union, its expansion to the east and the birth of the euro.

His legacy suffered after he left office, when the CDU, which he led for 25 years, was rocked by a finance scandal. His twilight years were also shadowed by family drama. His wife, Hannelore, committed suicide in 2001, after suffering from an allergy to sunlight. His son Walter published a book in 2011 detailing how his father focused exclusively on politics, ignoring his family.

It was Merkel, however, who delivered the ultimate political blow to Kohl, publicly breaking with her political mentor as the party was engulfed in scandal -- a move that would help her ascend to the post of party chairwoman in 2000. The wounds between the two never quite healed, leaving a complicated relationship.

Opening of the Berlin Wall

Still, Kohl’s position in post-World War II German history was already set.

“Helmut Kohl dominated German and European politics,” author Henrik Bering wrote in his 1999 biography of Kohl. “With Kohl’s election defeat in the fall of 1998, the last of the great Cold War leaders of the West left the political stage.”

Kohl saw his moment on Nov. 9, 1989, when the opening of the Berlin Wall gave way to throngs of East Germans swarming to the west.

With the help of West German Foreign Minister Hans-Dietrich Genscher, Kohl within three weeks introduced a 10-point plan laying out steps toward a single German state.

With the consent of the four World War II allies, the two German halves reunited on Oct. 3, 1990.

Tributes poured in from his former colleagues across the world.

Former President Bush, who was in power during reunification, called Kohl a “true friend of freedom.”

“Working closely with my very good friend to help achieve a peaceful end to the Cold War and the unification of Germany within NATO will remain one of the great joys of my life,” Bush said in a statement. “Throughout our endeavors, Helmut was a rock -- both steady and strong.”

Unifier of Germany, integrator of Europe

Former German chancellor Helmut Kohl's legacy includes putting a reunited Germany at the heart of Europe and helping create the continent's common currency, the euro.

German Foreign Minister Sigmar Gabriel says former German Chancellor Helmut Kohl was "a great statesman, a great German politician and most of all, a great European."

Gabriel said in a statement Friday that Kohl "did a lot not just to make German reunification happen, but also for European integration."

Kohl, the physically imposing German chancellor whose reunification of a nation divided by the Cold War put Germany at the heart of a united Europe, died Friday at 87.

We are in sorrow

Helmut Kohl, the physically imposing German chancellor whose reunification of a nation divided by the Cold War put Germany at the heart of a united Europe, has died at 87.

Kohl's Christian Democratic Union party posted on Twitter: "We are in sorrow. #RIP #HelmutKohl."

The daily newspaper Bild reported that Kohl died Friday at his home in Ludwigshafen.

Over his 16 years at the country's helm from 1982 to 1998 — first for West Germany and then for all of a united Germany — Kohl combined a dogged pursuit of European unity with a keen instinct for history.

End of division

Less than a year after the November 1989 fall of the Berlin Wall, he spearheaded the end of Germany's decades-long division into East and West, ushering in a new era in European politics.

Helmut Kohl was elected chancellor four times and, supported by a network of loyal political friends, he was the unchallenged leader of Germany's moderate conservative Christian Democratic Party (CDU) for more than a quarter of the 20th century.

There were many friends he promoted to top jobs. In return he expected absolute loyalty. Whoever tried to challenge his position in his party gambled with his own political future.

When opponents in his party tried to force him out of office in 1989 in an attempt to change the balance of power within the party, he delayed a prostate operation and visited a party convention despite suffering great physical pain. He was successful.

Helmut Michael Kohl was born to conservative Catholic parents on April 3, 1930, in Ludwigshafen, a small city along the Rhine River in western Germany.

He grew up in humble origins in a household headed by his father, Hans, who worked for the tax and revenue office of Ludwigshafen and also fought in both world wars. Hans and his wife, Cäcilie, raised Helmut together with an older brother and an older sister.

Kohl’s early life was shaped by the bombing raids of Allied planes during World War II. He never forgot about exhuming entombed dead bodies out of ruins together with other teenagers working for the youth fire brigade.

During the closing months of the war, he was a member of the Hitler Youth and drafted into an army training camp but never saw combat. His older brother, Walter, died in 1944 at age 19 while serving in the German army.

After his studies of law, political science, sociology and history, Mr. Kohl’s political career advanced in the CDU and by 43, he was national chairman. Along the way the act of categorizing people into supporters and opponents, good and evil, was a hallmark of Mr. Kohl's approach to politics.

He even had drilled his German shepherd Igo, as neighbors reported to a journalist, according to that world view.

To the command “Christian Democrat” the dog was friendly and wagged his tail. The command “Soz” — Mr Kohl's favourite word for Social Democrats and others to the left of his party — caused the dog to bear its teeth and snarl.

A rare setback for Mr. Kohl was his 1976 loss to Helmut Schmidt, a member of the Social Democratic Party, for the position of West German chancellor.

Six years later, as Schmidt faced a political crisis, Mr Kohl won the chancellorship after building a coalition with the Free Democratic Party, Germany’s liberal party, as a junior partner.

In office, Kohl seemed at times to lack the historical sensitivity required for such a high-profile job.

Some of his normalisation efforts met with howls of outrage from American and Jewish groups.

One of his greatest stumbles was the controversy surrounding his 1985 visit with President Reagan to a German military cemetery in Bitburg.

The state visit by Reagan was intended to celebrate the normalization of relations between the United States and Germany on the 40th anniversary of the end of World War II.

But a public relations disaster ensued when it was revealed that the cemetery contained the graves of 49 members of the Waffen-SS.

Secretary of State George P. Schultz wrote years later in The Washington Post that Kohl exerted tremendous pressure on Reagan to go through with the visit. Ultimately they visited the cemetery and the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp.

Kohl told Time magazine at the time of the Bitburg protest, “If we don’t go to Bitburg, if we don’t do what we jointly planned, we will deeply offend the feelings of our people.... This has nothing to do with the glorification of the Nazis... What are our young servicemen to think if our remembrance of the dead 40 years later is distorted in a way that does not do justice to the dead at all?

"Around 2,000 former servicemen are buried at Bitburg. Included among them are 49 members of the Waffen-SS. Of these 49, more than half were under the age of 20. If these young people had survived, they would have been amnestied under Allied regulations.”

Within Germany, Kohl was facing opposition to his attempts of normalization. Opposition leaders won energetic cheers by arguing that unification should not mean an end to the low profile that Germany’s military has kept since World War II. In the early 1990s, Kohl argued for a constitutional amendment giving the German military the clear right to participate in international humanitarian actions. He did not get the necessary two-thirds majority in the German Parliament, but the Supreme Court ruled that for peacekeeping missions the constitutional amendment is unnecessary.

For much of his career, Kohl was accompanied by his wife of 41 years, the former Hannelore Renner, who committed suicide in 2001. She suffered from a painful and incurable skin condition that forced her for years to live in a shaded house and avoid sunlight.

She was active in charity and made no secret of the difficulties and estrangements she felt because of her husband’s public career. She once likened her role to that of a dog who is expected to wait for hours and remain happy. She added: “I have learned from our dog.”

In 2008, Helmut Kohl married Maike Richter, a public official and economist 34 years his junior. A complete list of survivors was not immediately available.

In 1998, Kohl resigned from the chancellorship after voters rejected his party in the election, citing the high unemployment rate and other major problems he was unable to solve. It marked the end of an era for many younger Germans for whom he had been the only chancellor they had ever known, hence giving him the nickname the “Eternal Chancellor.”

Almost immediately after his resignation, Mr. Kohl was entangled in a financial scandal involving several million dollars in illegal donations to the CDU during his time in charge.

His party faced high penalties by the parliamentary administration and lost political credibility because Kohl, citing his word of honour, refused to mention the names of his donors, who had wanted to remain anonymous.

The scandal deepened when it was revealed that many relevant files had either gone missing or been destroyed.

Kohl deflected blame for the scandal, saying that opposition parties wanted to damage the achievements of his administration.

But in 2001 he agreed to pay a fine of about $143,000 and acknowledged a “breach of trust” for illegally accepting cash donations for his political party.

In return, prosecutors dropped criminal charges.

One result of the scandal was the decimation of a generation of CDU leadership tarred by association with Kohl.

Merkel, a Kohl protege

An East German politician and Kohl protege, Angela Merkel, then became the first woman to head the CDU.

Kohl hoped to be remembered for unifying the two Germanys and ushering the united country into the international community. “We Germans have learned from history,” he once said. “We are a peace-loving, freedom-loving people. There is only one place for us in the world: at the side of the free nations.”