PARIS: Aymar Delacroix lights up when he talks about the candidate who inspired him to become involved in French politics for the first time — at the age of 83.

Sitting in a bar with other supporters of centrist presidential hopeful Emmanuel Macron, many less than half his age, Delacroix recalls being struck by the confidence of the 39-year-old former economy minister.

“I said to myself ‘this guy looks interesting’. He was new, not like all the others who have been there forever,” said the smartly dressed father of four and grandfather of 10.

He and others — from students to business executives — have been meeting regularly in the mixed 17th district of Paris to talk politics and plan campaigning.

Macron’s “En Marche” (On the Move) movement claims to have raked in 200,000 such members in the 11 months of its existence, mostly moderates who feel alienated by the drift to the extremes of France’s traditional right and left.

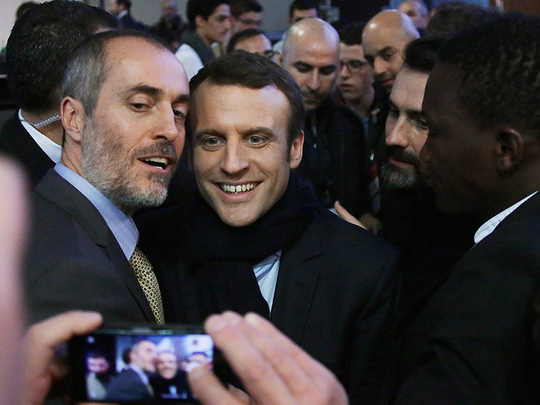

The ex-banker’s stunning rise from outsider to a frontrunner ahead of the two-stage presidential election in April and May is partly down to this army of grassroots devotees.

They have persuaded people to rallies and are spreading the word about a candidate who claims to be “neither of the left, nor the right” as he takes on traditional parties.

Polls currently show far-right leader Marine Le Pen winning the first round on April 23, with Macron or rightwing Republicans party candidate Francois Fillon also qualifying for a second round run-off on May 7.

The latest polls published on Sunday showed Macron stretching his lead over Fillon and easily beating Le Pen in the run-off in what would be a landmark shift in French politics.

Macron’s “marcheurs”, as well as serving as the eyes and ears of the campaign, have also been researchers contributing to his programme, set to be unveiled in full on March 2.

Delacroix, who believes “France’s heart is on the left but its wallet is on the right”, was among thousands of Macron supporters who went door-to-door last year asking voters what they felt was working in the country — and what was not.

“Terror attacks and unemployment were their main concerns,” he said.

After 25,000 questionnaires were collected, and the results analysed, the floor was thrown open to debate in some 3,500 local “En Marche” committees.

Emmanuelle Moors, an oil industry executive who attended a meeting on education that heard from teachers and psychologists, was blown away by the open debate.

“I saw they really were interested in finding what works best, that it wasn’t bluff,” the 50-year-old said as he sat with dozens of other supporters watching a screen showing a major speech by Macron in the city of Lyon.

Another regular at the “after works” meet-ups in Paris is Chloe Lescoules, a 25-year-old student from a family of artists in the Pyrenees mountains.

The petite blonde who is studying to become an auctioneer, had never been involved in politics before Macron swept onto the scene, promising to rejuvenate the economy and political system.

“He really has everyone’s interests at heart,” Lescoules said. “We all feel that way.”

Lescoules found a lot to like about the former investment banker, who as minister pushed through reforms to tightly-regulated professions, including auctioneering, making it easier for newcomers to get a foothold.

But Macron’s critics dismiss him as a lightweight, pointing to his delay in unveiling a fully-costed programme as proof he is short on substance and his quasi-messianic tones as the stuff of a “guru”.

And there remain serious doubts about his ability to appeal beyond middle-class voters, as well as the loyalty of his fan base.

Mehdi Guillo, a 23-year-old “En Marche” campaigner in the high-rise Paris suburb of Clichy-Montfermeil, admits that convincing voters in the deprived suburbs to rally behind the smartly-suited philosophy graduate is tricky.

Even arguing that Macron can help keep the National Front and its hardline policies on immigration and Islam at bay is not convincing.

“They say ‘We will no longer block Le Pen if it means continuing on with politics as usual for another 15 years.’

“They’re tempted to let the wolf into the coop,” he said.