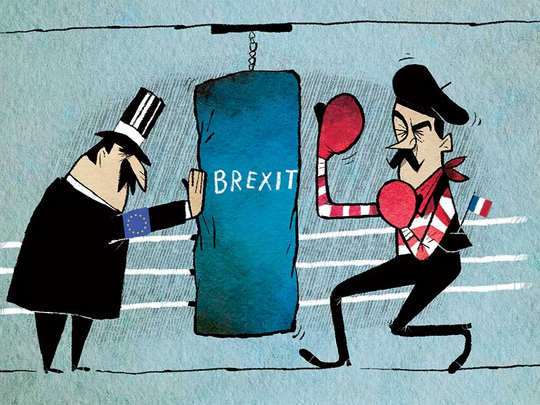

Former French prime minister Francois Fillon convincingly won on Sunday the country’s centre-right presidential primary. The result is significant as Fillon, who has made Brexit a key platform of his campaign, now stands a good chance of becoming the next French president, replacing Socialist Francois Hollande.

Fillon, like his defeated conservative primary opponent Alain Juppe, has made Brexit an election issue by arguing, for instance, that the 2003 Les Touquet migration agreement should be scrapped, which allows the United Kingdom to operate border controls on the French side of the channel.

Fillon has also said that London cannot, post-Brexit, remain the main Euro-denominated financial clearing centre. These positions have helped charge the political climate around Brexit in the country in a way that has intensified pressure on Hollande to take a tougher stance during the forthcoming United Kingdom exit negotiations that are anticipated to start next year.

What this French example underlines is how each European Union (EU) state has distinctive political, economic and social interests that will inform its stance on Brexit, with positions varying according to factors such as domestic election pressures, levels of Eurosceptical support within their populaces, and trade ties and patterns of migration with the UK. The varied, complex positions of EU states range from the UK’s fellow non-Eurozone member, Sweden, whose political and economic interests are likely to be broadly aligned with UK positions, to countries that have more complicated postures that will make the forthcoming negotiations potentially very tough.

Take the example of Spain, the Eurozone’s fourth largest economy, which recently ended 10 months of political deadlock with formation of a new government. While it benefits, economically, from around 300,000 UK citizens residing in the country, and has a significant trade deficit with the UK which might — other things being equal — favour softer negotiating positions, this picture is complicated by other factors, including Gibraltar’s future.

Madrid has already invited the UK government to post-Brexit negotiations on Gibraltar, the UK overseas territory on the southern Spanish coast, including proposals for joint sovereignty. The fact that Spanish Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy may play hard-ball in Brexit negotiations is reflected in his reported remarks to UK Prime Minister Theresa May in October that such a model will, under a ‘hard Brexit’, be the only way for Gibraltar to secure continued access to the European Single Market, which is key for its economy.

The scope for escalating tension between Madrid and London on Brexit is underlined by the fact that Gibraltar remains strongly opposed to enhanced political ties with Spain. UK Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson has doubled-down on this with his own “completely implacable, marmoreal and rocklike resistance” to Spain’s proposals.

Madrid’s negotiating position towards Brexit will also be shaped by the secessionist threat from Catalonia and Basque. Spain was strongly opposed to Scotland’s independence in the 2014 referendum, and will seek to scotch any attempts by that country, and/ or also Ireland and Wales, to try to secure special status in the EU post-Brexit.

Just as the UK government wants to secure the rights of its 300,000 citizens in Spain are comparable, if not identical, post-Brexit as before, Poland’s negotiating stance in the forthcoming negotiations will be heavily informed by its seeking of similar guarantees for the approximately 850,000 Polish-born residents in the United Kingdom. Indeed, Poles are now the most common non-UK country of birth for people across the nation.

For added leverage, Poland is lobbying here as part of the Visegrad group which also comprises Hungary, Slovakia, and Czechoslovakia. Collectively, there are more than a million Visegrad nationals in the United Kingdom and, while the group does not have a ‘qualified majority’ in Brussels to veto a Brexit deal, it will seek a wider, blocking coalition if its citizenry’s rights to live and work across the nation are not enshrined.

It is perhaps France, however, that may have the most difficult posture to Brexit, at least this side of the French presidential election in May. France has long had a complex, contradictory relationship with the United Kingdom in the context of EU affairs and, as the centre-right French presidential primary contest underlined, one fundamental reason Paris is likely to take a hard-line stance in the first phase of Brexit talks is political pressures from the 2017 race.

Hollande will likely lose his bid for a second term (potentially even failing to secure the Socialist nomination in the primary) in the face of revitalised centre-right, and also the eurosceptic, National Front candidacy of Marine Le Pen. Populist Le Pen is performing strongly in polls and is widely anticipated to win through the initial phase of presidential elections in April, knocking out the Socialist candidate (Hollande or otherwise), and then running-off in May against Fillon.

It is this context that, partially, accounts for Hollande’s positioning on Brexit with his argument the United Kingdom must pay a “price” for leaving. He perceives that any major concessions to the UK would feed political oxygen to Le Pen who is waging a populist, Brexit-style campaign, and has indeed promised a referendum on French membership of the EU if she got into power, an outcome which cannot be ruled out.

Election year pressures aside, however, the toughness of Hollande’s Brexit positioning, including his robust stance on future UK access to the single market, are reinforced by broader plans to tout Paris as a competing financial centre to London. Indeed, Finance Minister Michel Sapin and Brexit Special Envoy Christian Noyer, former Bank of France governor, have already started promoting Paris with key banks.

Taken overall, distinctive interests of EU states could make for very complex Brexit negotiations in 2017 and beyond. UK officials will therefore continue, through diplomatic outreach, to try to shape positions of countries that could be key allies or foes at the same time as Brussels seeks unified EU stances under leadership of Chief Negotiator Michel Barnier.

Andrew Hammond is an Associate at LSE IDEAS (the Centre for International Affairs, Diplomacy and Strategy) at the London School of Economics.