MANILA: When Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte summoned his security chiefs to an urgent meeting one Sunday night last month, his mind was already made up.

His military and law enforcement heads had no idea what was coming: a suspension of the police force’s leading role in his signature campaign, a merciless war on illegal drugs.

There was only one reason for the U-turn, three people who attended the January 29 meeting told Reuters. Duterte was furious that drugs-squad cops had not only kidnapped and murdered a South Korean businessman, they had strangled him to death in the headquarters of the Philippines National Police itself.

“He was straight to the point — ‘I am ordering you to disband your anti-drug units, all units’,” said Defence Secretary Delfin Lorenzana, who was at the meeting in the presidential palace.

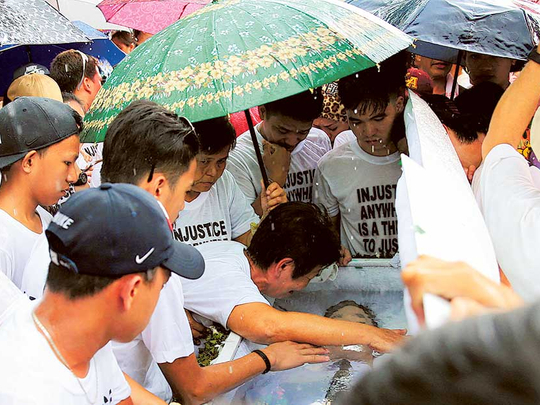

Philippine National Police chief General Ronald Dela Rosa whispers to President Rodrigo Duterte during the announcement of the disbandment of police operations against illegal drugs in Manila, on January 29. Reuters

Duterte decided that the much smaller Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency (PDEA) would take over the drugs crackdown, with support from the military.

It was a stunning turnaround by Duterte, who had until then stood unswervingly behind his police force through months of allegations that its officers were guilty of extra-judicial killings and colluding with hit men in a campaign that has claimed the lives of more than 7,600 people, mostly drug pushers and users, in seven months.

The blunt-spoken president had repeatedly defied calls from United Nations, the United States and the European Union to rein in his war on drugs, calling them stupid and ‘[expletive]’.

Duterte’s aides were used to his mercurial style, but they were taken aback that the killing of one foreigner would be enough to stop him in his tracks.

One explanation is that relations with South Korea are of huge importance to the Philippines for development aid, tourism, overseas employment and military hardware.

But security officials said it was the audacity of the killing of Jee Ick-joo and the attempt to use the war on drugs as a cover for kidnap and ransom that triggered his decision.

“It’s all about the Korean. That it happened at all, it’s really that [which] pissed him off,” Lorenzana told Reuters.

PDEA Director General Isidro Lapena, who was also at the meeting, hadn’t seen it coming either. He said in an interview that the president had lambasted the police force and told them that the “deactivation” and purge of its anti-drugs unit was now as important as the drugs war itself.

Police Director General Ronald dela Rosa told Reuters that Duterte had been “really mad” about the incident and, after the meeting, the president publicly denounced the police force as “corrupt to the core”.

The president’s legal counsel, Salvador Panelo, said the president, a former prosecutor, makes decisions strictly on the basis of the letter of the law. Activists’ allegations of summary executions had no supporting evidence, he said, yet to Duterte, Jee’s killing was irrefutable, audacious and embarrassing.

“The committing of that crime was so obvious,” he said.

Worried that the incident would dent the Philippines’ image in South Korea, Duterte sent Panelo to Seoul to apologise to acting president Hwang Kyo-ahn.

Seoul is Manila’s biggest supplier of military hardware, donating or selling fighter jets, patrol boats, frigates and trucks.

About 1.4 million South Koreans visited the Philippines in the first 10 months of 2016 — a quarter of all tourists arrivals — lured by beaches, golf and the sex industry. Korean tourists spend an average $180-$200 daily, and their overall spending is triple that of US visitors.

South Korea is the Philippines’ fifth-largest source of development aid and in 2015 invested $520 million in areas like power, tourism and electronics manufacturing.

About 55,000 Filipinos work in South Korea and the Philippines attracts Koreans studying English, over 3,700 of them last year.

A South Korean diplomat in Manila said there were no threats or pressure on the Philippine government over the killing of the businessman, but Seoul wanted a guarantee of safety for its citizens and a secure investment climate.

Hoik Lee, president of the Korean Chamber of Commerce in the Philippines, said South Koreans felt increasingly unsafe in the country.

The chamber’s membership has grown from 20 firms in 1995 to 500 companies now, including Samsung Electro-Mechanics, Hanjin and LG, but Lee estimated that the Korean community has shrunk by about a third to 100,000 people since 2013 despite the bright economic outlook in the Philippines.

“Police should protect us not kill us,” Lee said. “That is why we are very upset and very shocked.” The number of Koreans murdered in the Philippines averages about 10 each year, accounting for a third of all Korean nationals killed overseas, according to Seoul’s foreign ministry.

However, South Koreans are perpetrators of crime as much as they are its victims in the Philippines, says the police Criminal Investigation and Detection Group, which has a Korean desk handling cases of kidnappings, murder, robbery, theft, extortion and fraud, mostly in Korean communities, where mafias operate.