On the morning of December 5, cram schools in Kota discussed, for the first five minutes of the lecture, what the young children in the classroom could do if they didn’t become engineers or doctors. The students were advised to talk to their teachers after every class if they were under any kind of stress.

Every year, teenage boys and girls arrive in hordes in Kota, a riverbank town 256 kilometres south of Jaipur in the western Indian state of Rajasthan, to chase their dream of becoming engineers or doctors. So it wasn’t routine to tell them about alternative careers — there was a reason. The town was in the news because some students, unable to cope with pressure, had committed suicides. On December 3 and 4, two more had hanged themselves.

“Meri apni laparwahiyon se mujhe yeh kadam uthana pad raha hai. Papa, mummy, ho sake toh mujhe maaf kar dena (I am forced to take this step due to my own mistakes. If possible, papa, mummy, forgive me).” This is what 19-year-old Varun Jeengar scribbled in his four-line suicide note on the night of December 2 before hanging himself in a small room in Kunhadi’s Adarsh Nagar. He had come here from Ludhiana in August to join the 77,000 students at Allen Career Institute and pursue his dream of cracking the All India Pre-Medical Test (AIPMT).

The next day, 17-year-old Satakshi Gupta became the 15th student to have killed herself in Kota this year. Hailing from Ghaziabad, Gupta hanged herself at her uncle’s Jawahar Nagar house. She was preparing for JEE, the entrance exam for admission to one of the 16 Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs).

Empirically, 15 may not be an alarming figure in a city with a population of a million and where more than 100,000 new students arrive every year, but it’s not a small number either.

“Numbers are misleading. Suicide is only tip of the iceberg. Not every stressed, depressed student gives in to pressure and ends his life but it is an irrefutable fact that Kota, as host to these hundreds of thousands of students, has failed to sensitively and effectively take care of their needs and requirements,” says Dr Ravikumar Surpur, Kota district collector. In November, he sent out an elaborate guideline on improving the educational environment to coaching institutions.

Kota, or the “coaching city” as it’s known, has attracted a lot of bad press this year because of students killing themselves. And though different Indian newspapers quote different numbers (some peg the figure at 27, more than double of last year’s 11), the cause in most cases is the same — “study pressure”.

Rigorous study schedule, high-pressure environment, competitive exams and stress of living alone take a toll on many students, pushing some of them to end their lives.

Psychiatrist Dr Devendra Vijayvargiya says the fear of failure is a major cause of student suicides. “Students from different parts of the country land up in an unfamiliar place and those who can’t cope develop an inferiority complex in the intensely competitive environment,” he was quoted in a news report in “Hindustan Times”.

Vijayvargiya’s observation is reflected in 18-year-old Anjali Anand’s suicide note. “Hamara agar selection nahin hua toh hum aap logon se nazrein nahi mila payenge. I am sorry. Mein apni marzi se aaj apni life khatam karti hoon (I won’t be able to face you if I am not selected. I am sorry. I am ending my life of my own volition),” she wrote in the suicide note before she ended her life in her hostel room at Rajiv Gandhi Nagar on October 31.

Kota developed into a coaching hub in the late 1980s. Over the years, its reputation grew as students from these institutes succeeded at various entrance exams. About one in every three students who make it to the top technical and medical schools in India is from cram schools in Kota. Coaching is a big Rs20 billion (Dh1.1 billion) industry with about 40 big centres here. In the last 25 years, Kota has produced about 150,000 engineers and more than 100,000 doctors.

At the Kota government medical college, Dr Bharat Singh Shekhawat, the professor of psychiatry, says he handles at least six or seven cases of depression and stress among students every day. “The Indian Express”, which did a 5-part series called “Inside The Kota Coaching Factory” in November, quoted him as saying: “Most of them have stepped out of home for the first time and here they are all expected to fit into a certain mould, which is very stressful. Just the amount of rules and regulations can take a toll.”

In the series, one student spoke about the gruelling schedule that he has to follow in Kota. “I am under a lot of pressure, I am preparing for both my Class 12 exams and AIPMT, I don’t know what to concentrate on,” said 17-year-old Sawan Kumar from Araria in Bihar. He joined a pre-medical coaching course here in 2014. With less than six months to go for both the exams, Sawan said: “I wake up at 9am and after freshening up and doing pooja [prayer] in an hour, I study straight till 1.30pm. I attend classes at Allen Coaching Institute from 2pm to 8pm and then after dinner, study from 9pm to 3am. But I feel nothing is enough.”

A police officer blames the coaching institutes for the suicides. In the beginning, he says, the institutes would take students only after checking whether they had the aptitude for the highly competitive exams. “They would dent admission even after recommendations from many of our senior officers, but now they admit everyone. One coaching institute owner has set a target of 200,000 students in his classrooms by 2020. They have stopped saying no to parents of students who don’t have what it takes to follow the rigorous routine of cram schools,” he adds.

In his November 4 letter sent out to coaching centres, Surpur called for mandatory career counselling of children with their parents prior to admission to take into account the current credentials of the student (as inferred from various entrance tests and academic scores). “It should also be done concurrently in such intervening periods that the institution finds appropriate. The utilitarian value of each of such counselling is to keep the expectations realistic and to suggest alternative professional course that the child may be suitable for,” the letter noted.

The coaching institutes also follow a process of batch segregation based on periodic evaluation since many children complain of discrimination and disparity in the quality of education, which provides fuel for frustration and hampers motivation level. “The faculty focuses on the top 100 students — provide them luxury cars for transport to the centres. They get to take lifts, and teachers follow their nutrition, since this group will produce toppers [in various competitive exams]. The rest get second-grade focus and faculty,” says Himanshu Mittar, a local broadcast journalist who has covered the industry for many years.

“Parents on average spend around Rs250,000 to Rs300,000 every year on coaching. When the children find themselves lagging, they feel guilty and can go into depression,” he adds. Some of them commit suicide. According to Kota police data quoted by “Hindustan Times” in a report on October 19, 72 students have committed suicide in the city in the past five years.

However, Allen Career Institute senior vice-president C.R. Chaudhary blames parents for the burden of expectation they place on their children. “Pressure is the biggest issue, but parents are most responsible in these cases,” he says before listing out the steps he has taken to ensure that students find an outlet.

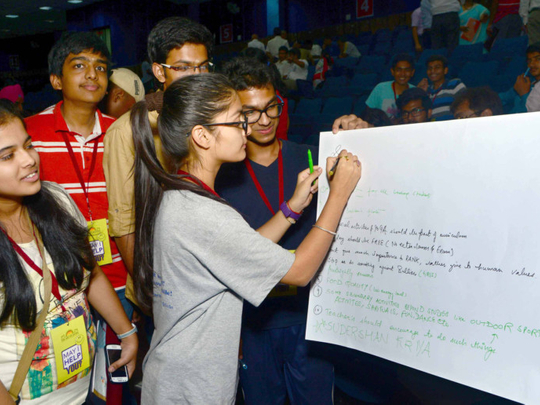

The Kota district administration conducted a workshop on October 18 with psychiatrists, paediatricians, physicians, clinical psychologists, educationists, spiritual leaders, parents and students. During the workshop, it was found that the entire fee is deposited prior to admission, and in case the child realises a serious mismatch of requirements of the course and his aptitude, it becomes difficult for him to seek a refund.

At a meeting on December 10, state’s chief secretary C.S. Rajan called for a strategy to help students manage stress levels better. Among the steps proposed, one was to make an easy exit policy for students, which will involve proper refund. “There is a feeling that some regulation is needed. The government has the power to implement these regulations and coaching institutes will have to follow them. We will not leave it as a matter of choice,” “The Times of India” quoted Rajan.

The district collector’s letter had already directed coaching institutes to keep Sunday off as a mandatory one-day break in a week. Earlier, students got only a week-long Diwali break in the entire year, while Sundays were meant for tests.

The collector’s guidelines also talk of chronic absenteeism. A student being absent for a significant number of days without any valid reason should sound the alarm; the child should be monitored for his mental status and parents be informed accordingly, the letter said.

Had this been followed, Jeengar would probably have been alive today. He attended classes only for five days in August, the month he took admission, and two days in September. He was absent for whole of November and ended his life in December.

Rakesh Kumar is a writer based in Jaipur, India.