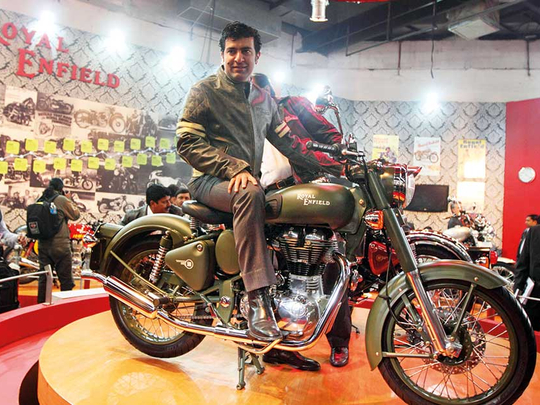

London: As Royal Enfield boss Siddhartha Lal sat astride his company’s new motorcycle and posed for photographs at the EICMA Milan motorcycle show earlier this month, he might have paused to consider how different things were only a decade ago.

In 2007, Royal Enfield sold 32,000 units but, under Lal’s leadership, the company’s fortunes — and the share price of its parent Eicher Motors — have been transformed.

This year, the business expects to sell 800,000 motorcycles in India. It has ambitious plans for international expansion, and a new R&D facility in Leicestershire marks a return to the UK, where Royal Enfield motorcycles were first produced in 1901.

Initial struggles

“It was still a very fragile brand in 2007,” says Lal, as a taxi carries us through country roads on the way to the R&D centre at half past seven on a crisp, bright morning. He is sitting in one of the back seats, but leans forward slightly to check the traffic in both directions when the car stops at a junction. “Selling every motorcycle was a struggle. Convincing dealers to spend time and energy, going to suppliers; they’d treat us like ... well, not so well. Let’s put it that way.”

In 2004, Lal took over as CEO of the Eicher Motors group, the business founded by his father Vikram, and set about selling off 13 of the company’s 15 brands. That left just Royal Enfield and truck maker Eicher — the two that he believed could thrive. He set a goal for Royal Enfield. “Our ambition was to sell 100,000 units [per year].

Then the virtuous cycle starts; dealers start making a bit more money, suppliers start paying more attention. That 100,000 units didn’t come until 2012. But this year, we’ll sell more than 800,000. That was absolutely inconceivable. I thought we’d be a stable company, but not as big a sensation as we are in India now.”

Although all of its bikes now roll off production lines in Chennai, eastern India, Royal Enfield can trace its lineage back to Victorian England. The “Royal” epithet was added when the company was called upon to create parts for a munitions factory in the 1890s.

Its first engine-powered two-wheeler was built in 1901, giving it a claim to being the oldest motorcycle brand in continuous production, and it went on to produce models for use in both world wars. One came equipped with a Vickers machine gun-mounted sidecar and, most famously, there was the “Flying Flea”, a lightweight bike that was designed to be dropped by parachute alongside airborne troops, who used it to carry messages to ground forces in the Second World War.

In the Fifties and Sixties, Royal Enfield was synonymous with the cafe racing scene in the UK, and also became popular on the other side of the Atlantic. James Dean owned one and Steve McQueen had several, one of which fetched $146,000 (Dh536,252) when it was sold at auction in 2013.

In 1955, Enfield India began manufacturing under licence in Chennai (then called Madras) and began using the Royal Enfield name in 1999. By that time the UK production had ceased for three decades; the British firm went bankrupt in 1967.

The bikes became a familiar sight on the subcontinent, thanks largely to their use by the army and the police. But, Lal says, in the Nineties, they struggled to compete against the powerful Japanese.

So he set about building a brand, but not by signing expensive endorsement deals with Bollywood stars and cricketers.

“It feels absolutely wrong to give somebody a lot of cash to say, ‘I ride this motorcycle’. And,” he laughs, “we didn’t have the money”. Instead the company cultivated a community of fans by hosting rides, such as “Himalayan Odyssey”, which sees Royal Enfield owners cover the journey from New Delhi to Leh over 18 days.

Royal Enfield still accounts for just 6 per cent of all motorcycles sold in India but, Lal says, this translates to 10 or 12 per cent of the industry’s revenue and to a 20% profit share.

‘High profit share’

“That’s a term I learnt from Apple. They say, ‘we have no market share, but we have a high profit share’.” Revenue was pounds 827m last year and the company accounts for the lion’s share of Eicher’s overall profit. More than 95 per cent of the company’s bikes are sold domestically, but Lal is bullish about the prospect of it becoming a “truly global brand”.

The decision to open its North American headquarters in Milwaukee, the home of Harley-Davidson, and to launch a duo of models powered by a new 650cc twin engine last week has, in some industry experts’ eyes, put Royal Enfield in direct competition with the famous American marque for the first time in decades. But Lal isn’t having any of it. “We’re not going head-to-head with anyone,” he says.

Lal, who is known as “Sid” by his colleagues, speaks softly and has a modest air. So when he announces that “in our bumbling and gentle way” the company is aiming for “world domination” it hits home. But, says Aston University professor of industry, David Bailey, it will have its work cut out.

—The Telegraph Group Limited, London 2017