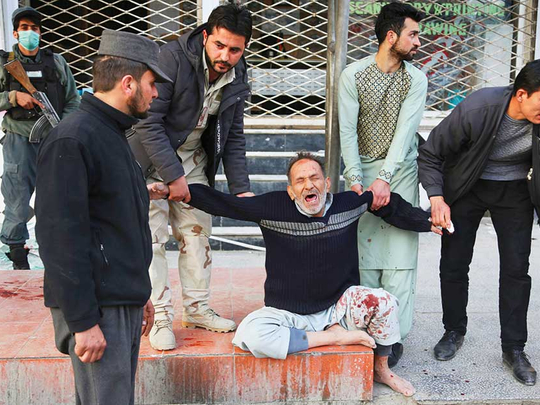

New York: They were hardly the first Taliban attacks in the capital. Still, there was something particularly alarming in their scale and implication about the pair of episodes, just a week apart, that rocked Afghanistan: a hotel siege that killed 22, then a car bomb, loaded into an ambulance, that killed 103.

But the question of why — why target bystanders, and in such numbers — is perhaps best answered not by peering into the minds of the attackers but by examining the structure of a war that increasingly pulls its participants toward the senseless.

Whether the week’s events will translate into a long-term gain for the Taliban or serve only as a terrible but temporary show of force, the attacks embody the trends toward violence and disintegration that appear to be only worsening in Afghanistan.

A war engineered or chaos

The war’s participants embarked on what they thought was a traditional battle for control of Afghanistan’s territory and for the allegiance of its people. But over more than 16 years, without setting out to do so, they have remade it into a war over one issue: whether or not the country can have a central, functioning state.

For the US-led coalition and its Afghan partners, the goal was simple: Set up a government, help it consolidate control, and wait for Afghans to reject the Taliban in favour of stability.

■ Daesh gunmen attack army compound

■ Exercise tracking map highlights locations of troops

The Taliban, which deny the foreigner-backed government’s legitimacy, sought to topple it.

- Mullah Hamid | Taliban commander

Because both sides treated Afghanistan’s governance as a matter of all-or-nothing survival, the Taliban had every incentive to create chaos.

“I see a lot of US complicity in this,” said Frances Z. Brown, an analyst at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and former member of the National Security Council.

With the Taliban unable to win outright but the Americans unwilling to admit defeat, she said, each side has privileged short-term escalations. That has validated the Taliban’s view that the group must undermine the state, including through attacks in Kabul that expose the government’s weakness.

“Trump’s strategy is based on a fighting machine — to send more troops,” said Mullah Hamid, a Taliban commander in southern Afghanistan. “If they are giving priority to the military option, we are not weak. We can reach our target and hit the enemy.”

The tit-for-tat violence has taken on a logic of its own, overwhelming other options.

“There has not been any channel of talks ongoing between the High Peace Council and the Taliban,” said Maulavi Shafiullah Nuristani, a member of the government body tasked with exploring negotiations. “We never had any direct contacts with them, except for indirect and personal contacts.”

Nuristani said the peace council’s offices, located a little more than 200 yards from the site of Saturday’s car bombing, would close for two days — “until the rooms and our offices are cleaned of debris and broken glass.”

American strength as a weakness

As US-led forces have escalated in response to Taliban gains, they have unintentionally pushed the Taliban toward grislier violence. Air strikes have forced the Taliban to lie low in rural areas, where they prefer to operate, seizing territory and extorting from locals.

Instead, they have shifted towards terrifying if brief guerrilla-style attacks in Kabul and other urban districts, where US air power is of little use. Though this gains them no territory, it allows them to humiliate the government where it is most visible.

The group’s internal dynamics have aligned with its shifting incentives, elevating officers who favour large-scale attacks on civilians.

Sirajuddin Haqqani, who leads the once-semi-autonomous Haqqani network, a terrorist group closely associated with Al Qaida, now serves at the Taliban’s No. 2 leader and de facto military planner.

“The Taliban and the Haqqani are the same,” said Sayed Akbar Agha, a former Taliban commander. “Only the government is differentiating between them.”

Weakening the Taliban’s ability to act as a traditional insurgency that holds territory, though logical, also compels them to prioritise their role as terrorist group, as last week’s attacks show.

A destabilized proxy war

For as long as Afghanistan’s war has raged, Pakistan, which plays a double-game with the Taliban, has been at the Centre of its seeming intractability.

President Donald Trump, following two presidents who tried and failed to rein in Pakistan’s meddling, publicly chastised Pakistani leaders this month, freezing security aid to Pakistan.

But Brown said the United States seemed unready for the all-out-inevitable response to its confrontation with Pakistan. “If you start on the path of escalating pressure, you have to be ready for the other side to escalate,” she said.

Officials in Kabul worry that Trump’s hard-line approach could, in at least the short term, worsen the situation.

A drift towards endless conflict

In theory, a peace deal could bring all sides together. But a half-generation of fighting has eroded trust and polarised the combatants. While wars have ground down to peace before, it required a broker. Here, none seems to exist.

“The international community is absolutely not equipped for that,” Brown said.

Diplomats are stretched thin trying to keep the government from collapsing amid political squabbles, another symptom of its weakness after years of war.

The Americans’ strength is also a hurdle in diplomacy. The United States is too influential to circumvent but, with the State Department gutted, it lacks the capacity or attention to seek a peace deal, which Trump seems to have little interest in anyway.

The growing toll for civilians is not changing the calculus for any of the forces conducting the war.

Gen. Joseph L. Votel, who as head of US. Central Command has authority for the war, was asked on a visit to Jordan about the latest attacks in Kabul. He said they only affirmed US strategy.

“It does not impact our commitment to Afghanistan, our commitment to the mission, and seeing this through,” he said.

Asked whether victory was still possible, he gave the same answer US generals have given for over 16 years: “Absolutely, absolutely.”