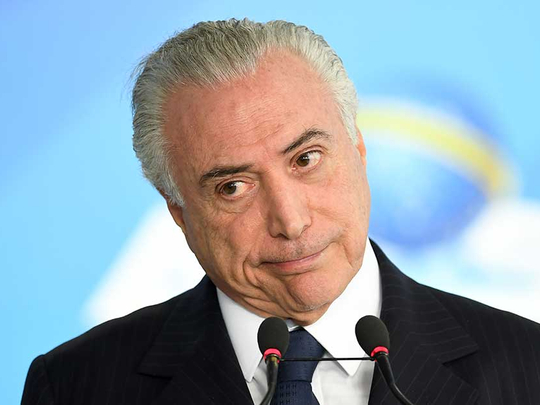

Brasilia: Brazilian president Michel Temer rode to power last year by helping get his ex-ally Dilma Rousseff impeached, but now he could be forced from office himself.

Here are five key chapters from a tumultuous 14 months culminating with Monday’s filing of bribery charges against him by Prosecutor General Rodrigo Janot.

Replacing Dilma

Rousseff’s vice president Temer temporarily replaced her as head of state on May 12, 2016, after the Senate voted to hold an impeachment trial over charges that she broke government accounting rules.

The leftist leader was finally dismissed on August 31 and the conservative Temer took full office to see out the mandate to late 2018, launching austerity reforms to fix the stricken economy.

Heads roll

Three of Temer’s all-white, all-male cabinet were fired or resigned between May and June 2016 over a vast corruption scandal linked to the state oil firm Petrobras. They were the first of a slew of casualties from Temer’s inner circle as investigators with the so-called “Car Wash” operation closed in.

Another key ally, the former lower house of congress speaker Eduardo Cunha, would be jailed in March 2017 for taking bribes. He had been the main driver of the Rousseff impeachment.

Reform battle

Temer says his main priority is austerity reform to whip Brazil’s economy back into shape and exit a two-year recession.

On December 13, 2016 Congress approved a 20-year public spending freeze, a central plank in the unpopular policy.

However, other pending measures to tighten pensions and loosen labour laws risk have been severely disrupted by Temer’s latest legal problems, as well as violent street protests.

Temer bombshell

“Car Wash” action ramped up in April 2017, when the Supreme Court authorised prosecutors to probe more than 80 senior politicians for corruption based on allegations made in plea bargain testimonies.

The accused include eight ministers, 29 senators, 40 lower house deputies and three governors, many of them close to Temer.

On May 17, a recording of Temer supposedly discussing the payment of hush money to the jailed Cunha emerged. Two days later, the Supreme Court authorised an investigation into suspected corruption and obstruction of justice.

Temer got one break, however, when the top electoral court decided on June 10 to acquit him of charges that he and Rousseff won their 2014 election on the back of corrupt donations. A guilty verdict could have seen Temer stripped of his mandate.

Corruption charges

On Monday, Janot charged Temer with receiving a bribe from a major meatpacking company. Further charges — obstruction of justice and belonging to a criminal organisation — are expected to follow.

Temer is now the first sitting Brazilian president to face criminal charges.

However, for the charges to stick and a trial to open there must be a two-thirds majority vote in the lower house of Congress. Temer, who denies all the charges, believes he has enough support to bar the charges in the legislature for now.

However, Janot’s strategy of presenting charges one by one will mean the crisis drags on, possibly weakening the president by the day.