Johannesburg

Portia Lekgoto faced a dilemma: how to take her three-year-old daughter to a doctor without missing a day of work while waiting in line at one of only two public health clinics in the South African shantytown of Diepsloot.

She decided to take her daughter to Quali Health, a new private clinic that a friend had told her about. While she had to pay 250 rand (Dh73 or $19) for the visit, she finished the consultation by mid-morning.

“I am going to now drop my daughter off at her granny with the medication we have been given and then I will go into work,” Lekgoto, 34, said at the clinic. “This place, the staff are friendly and it’s nice and clean. I’ll definitely come back.”

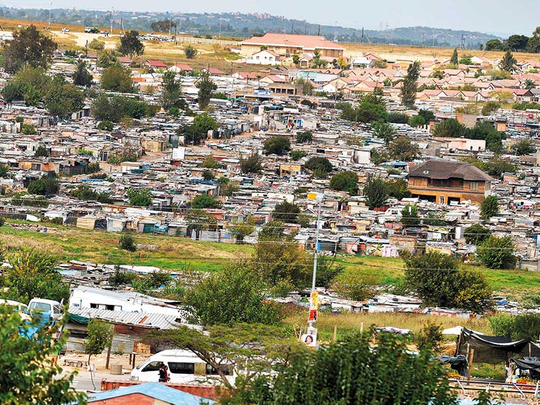

People walking into a well-resourced health centre in a township and getting immediate help is an unusual sight in poorer areas of South Africa like Diepsloot, a shantytown of about 140,000 people that was born a year after Nelson Mandela came to power in the first all-race elections in 1994.

Nthabiseng Legoete |

The more than 80 per cent of the nation’s population with no medical insurance depend on a public health system that the World Health Organisation ranks as one of the worst in the world or on traditional healers who usually provide herbs as medicine. Quali Health was started in May by Nthabiseng Legoete, a 37-year-old doctor, after visiting India, where she saw people with no medical insurance using private care at a hospital in Bengaluru.

Low-cost health care

By September the clinic in Diepsloot, which offers primary care, was turning a profit and is now seeing about 3,000 patients a month. In March, with funding from the Development Bank of Southern Africa, she opened clinics in Tembisa, Soweto and Alexandra townships around Johannesburg, South Africa’s commercial hub.

“I chose to visit India because I knew there were pockets of excellence in terms of low-cost health care,” Legoete, dressed in silver sneakers, jeans and a white doctors coat, said in an interview at the clinic. “I saw a production line approach to a lot of services, where one person is dedicated to one function and becomes better and faster at that one thing. It creates a seamless process through the entire service.”

India and South Africa share some common health problems: high vulnerability of young children, poor sanitation and diseases such as HIV, malaria and tuberculosis. Neither country has a well functioning public health system, according to WHO. India ranks 112 out of its 191 member states, while South Africa is 175.

“There’s a massive, massive shortage of quality affordable medical care,” BPI Capital Africa analyst Kate Turner-Smith said by phone from Cape Town. “At 250 rand, this is still a day’s wage for many to see a doctor, but it does mean getting better sooner and that is positive both for the person and for national productivity.”

Health Ministry spokesman Joe Maila didn’t respond to calls, text messages and emails requesting comment.

Quali clinics aren’t cheap for the people it targets and who may earn on average about 3,500 rand ($266) a month. Yet the fee buys patients access to doctors, physician associates and nurses, medication, antenatal sonar, and heart, blood and blood pressure tests. Circumcision or a Pap smear test, including the lab fees, costs 150 rand. General practitioners in Johannesburg charge as much as 500 rand a visit for a consultation alone, and the average cost for insurance is 1,550 rand per person per month.

After Legoete took all her savings and borrowed from friends and family, she opened the clinic that operates seven days a week from 8am to 8pm.

“Our target market is employed people who are currently reliant on the public health system,” she said. “They are being forced to choose between going to work or getting a health check.”

— Bloomberg