Hvala… that is probably the only word of Serbian you’ll need to get by in Belgrade. It means thank you, by the way, and it’s a phrase you’ll find yourself using constantly given the hospitality of this multilayered city; steeped in history, yet desperate to compete as modern and vibrant.

Belgrade, the capital of Serbia, sits just on the nook of where the River Sava meets the River Danube. Local legend has it the Sava is female, and the Danube male; with Belgrade marking the point they meet to kiss before heading to the Black Sea.

The city itself is pretty much separated by the River Sava. On one side is the new part of town, populated with hard-to-miss Soviet-style high-rise tower blocks – not the best first impression.

Amidst this sprawling residential area lies Belgrade’s leading shopping mall – the USCE Centre, a national exhibition stadium, and modern restaurants like the aptly named Novak – linked to the world’s number one tennis player and Serbia’s finest current export, Novak Djokovic. It’s the new town of Belgrade, if you like.

Almost symmetrically opposite though, is the old town – commonly referred to as Stari Grad – which shows off Belgrade’s rich history and culture in all its glory.

Belgrade was first given city status by the Romans in the second century, thanks to its vibrant trade markets. With that, its importance grew and over the next thousand or so years, it was constantly fought over, changing hands several times in the process.

In the early 1600s, Belgrade was conquered by the Ottoman Empire, and became a key seat of the territory that sprawled through most of the Middle East, and parts of North Africa and Southern Europe. The Ottomans were involved in the area for almost three centuries, leaving a lasting Islamic and Arabic legacy. The city was fought over several times during the period, particularly in the infamous Austro-Ottoman wars, which destroyed large parts of it.

Despite its rich history, Belgrade is perhaps best remembered for being the capital of Yugoslavia, which – in more recent times – assumed Serbia as one of the countries it unified under a communist system of federal government.

The city’s chequered past has provided it with a fascinating array of features. Indeed, walking through Stari Grad, you could be visiting more than one country.

You move from a street that feels like a busy Eastern European capital, to one that would be well placed in small town in rural Italy, and around another corner to find a feel of Paris.

You could be anywhere in Europe, but thanks to the intimate nature of the city, it retains a unique vein running through a hotchpotch of other influences.

The centre of Belgrade is formed as a strip known as Knez Mihailova. The pedestrian-only zone is buzzing with life morning, noon and night, and is overlooked by impressive buildings and mansions built during the late 1870s.

The atmosphere is infectious, with many inviting places to eat or drink amid lively chatty crowds and street performers. But be warned, in busy areas like this begging is a big problem. Women holding babies, or even lone children, regularly ask for food and money.

My hotel, the four-star Belgrade Art, was right in the hustle and bustle of Knez Mihailova. Although it was a bit noisy at times, it was central, modern and affordable, so an ideal base for my whistle-stop tour of the city.

It was refreshing not to see many fast-food chains or international brands in Belgrade. The city has no Starbucks and not a single Subway.

This is one of the great advantages of Belgrade; dining is cheap – a meal at a high-end restaurant for two costs about €40 (Dh200), with equally delicious and affordable eateries scattered throughout the city.

The Gnezdo Restaurant is a true gem. Tucked away inside a run-down three-storey house on Branko’s Bridge (reportedly named after Serbian poet, Branko Ćopić, who jumped to his death from the bridge), this independent restaurant may be crumbling on the outside, but the interior is cosy, bright and warm. It offers a small organic menu of around 10 dishes, each skilfully prepared using the freshest local ingredients – the carrot and ginger pottage is an absolute must!

The city may have been fought over on and off for several centuries, but Belgrade has held on to a rich offering of architecture. The Belgrade Fortress situated in Kalemegdan Park is an imposing feature and one of the oldest in the country.

For centuries, the city’s population was concentrated within the walls of the fortress, which was built to protect the city from invasion. Interestingly, part of the fortress has huge white stone walls – built to signify Ottoman rule. Other parts have red brick additions – proof of the brief periods when the Austrians controlled the city. The most interesting feature though, is the quaint St Petka’s Church.

Built on a spring, it is named after the woman, Saint Petka, who was thought to have been buried on the spot centuries ago. The spring water is believed to be sacred and beneficial to women, while the entire interior is designed using handcrafted mosaic tiles, portraying biblical imagery in the most fascinating way.

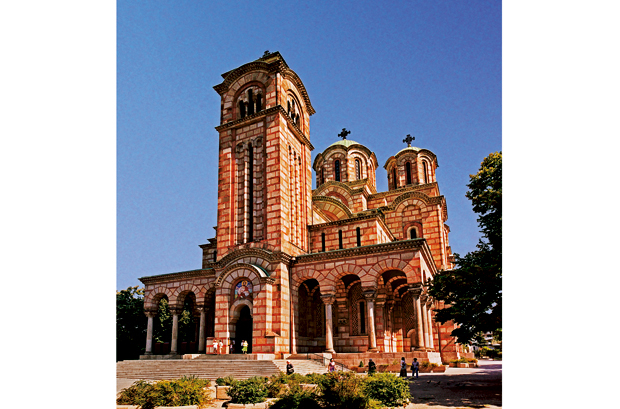

Belgrade has lots of churches, many grander than this, like the St Sava Temple, and many more architecturally impressive, such as St Mark’s Cathedral. But it is the feeling of spirituality that most impresses at St Petka’s – regardless of your religion, this is a place that touches you.

Of course, the Balkans wouldn’t be the Balkans without the nightlife, and countries like Croatia and Bulgaria draw millions of visitors each year, largely due to their entertainment offerings.

While Belgrade lags behind them, there’s no shortage of lively nocturnal activity. Take the Splavlova strip on the banks of the Sava, with its rows after rows of bustling bars on steadied boats, which offer great views of the city.

Visit the district of Skadarlija, essentially the old Bohemian Quarter, and you’ll feel like you’ve stepped back in time. It dates back to the late 19th century when its kafane (restaurants and taverns) were the meeting point of the greatest minds in Belgrade – the artists, musicians, painters and poets would line the cobbled streets to eat, drink and exchange ideas.

Today creative types still flock to build on this age-old atmosphere, buoyed by the area’s liberal, free-thinking spirit. Here you can savour the feel of a city steeped in history, tradition and culture over a plate of traditional Serbian food – think sarma (stuffed cabbage rolls), podvarak (roast meat with sauerkraut) or a delicious moussaka.

Skadarlija is unique, but another area of the city sums up the two halves of Belgrade in five square kilometres – the diplomatic quarter, where key government departments are housed. The foreign ministry once had the grandeur to compete with some of the finest in western Europe. But impossible to miss, just a few hundred metres away is the former home of the defence ministry.

The two buildings, which sit opposite each other, are remnants of the Nato-led bombings of Yugoslavia in 1999 – a stark reminder of just how recently the country and region were affected by instability.

The buildings still have windows blown out and metal poles jutting out of loose hanging concrete like bones stripped of flesh. This might seem unsightly at first glance, but the government has chosen to leave the site as it is to protect its heritage.

To keep a stark reminder of just how much the country has suffered may not be a bad idea. Belgrade is proud of its past, but in a region that’s becoming increasingly ‘European’, the city seems determined to move on to a brighter future.

This story first appeared on Friday in April 2013