For Susheela Raman, music is “all about escaping definition”. If the British-born and based musician seems emphatic on this point, shared over coffee in a park in north London, it’s because she has never really fitted in anywhere. Born to Tamil parents, Raman has spent acareer shrugging off labels: world music (“aracist marketing category; Ihate it”); ethnic (“I’ve often been told I should sound ‘more Indian’”); feminist. “I’m always striving for expression that could go beyond gender, beyond ethnicity,” shesays.

Her latest project is equally liberationist in spirit. On September 30, Raman will host Sacred Imaginations at the Barbican Centre, a concert of “sacred music for secular people”. The line-up, curated by Raman and her husband/music partner, Sam Mills of Real World Records, boasts esoteric virtuosos from around the globe who are united in their working knowledge of eastern and early Christian music. Parts of it will, says Raman, be like “plugging into something from the fourthcentury”.

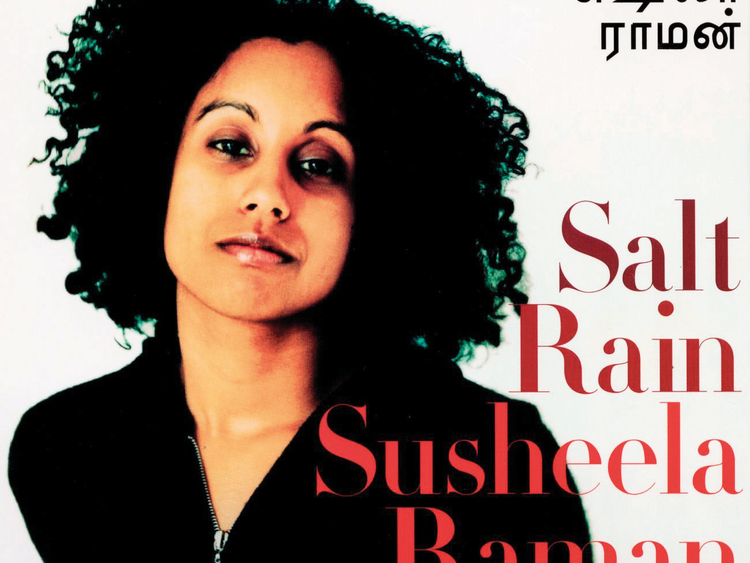

Raman has been mining this intersection between ancient and modern since her 2001 Mercury-nominated debut, Salt Rain. That record was abricolage of genre-defying originals and reworked ancient devotionals, sung in English, Tamil, Sanskrit and Hindi. Six albums on, she remains an independent artist with a well-stamped passport, having studied with Bauls in Bengal, Sufis in South Asia and having benefited from the tutelage of Tamil Nadu devotional matriarch Kovai Kamala.

For Ghost Gamelan, Raman’s forthcoming seventh album, she went to Surakarta, Indonesia in search of Gamelan musicians. Of her collaborations generally, she says: “Many of the traditions Iwork with happen to be quite patriarchal. The qawwalis [Sufi singers from South Asia], for example: their daughters aren’t allowed to sing. But Iwanted to penetrate that [scene], to earn theirrespect.”

Working with qawwalis on her 2013 album, Queen Between, was rewarding, says Raman, although initially difficult. Indonesia was also tough. “The self-determining woman artist is something they don’t recognise — though we managed to transcend that in the end; it was a great experience.”

Sexism, of course, isn’t just the preserve of the east. She empathises with the frustrations expressed by Bjork in a famous 2015 interview with Pitchfork, concerning the microaggressions female artists face. “She’s one of my big heroes. I always think: what would Bjork do?”

Increasingly, Raman finds herself aching for female collaborators. Abida Parveen, doyenne of the qawwali world, was just out of reach for Queen Between (“I couldn’t afford her fees”), but Raman is buzzing with enthusiasm over Lucie Antunes, the Parisian marimba and vibraphone percussionist who guests on Ghost Gamelan. “I was gobsmacked the first time I saw [footage of] her performing. Its like she’s talking in tongues. She’s from that Stockhausen/John Cage sort of world.”

Raman’s longest-standing collaborator, Mills, is still very much her linchpin. But it is only after the Brexit referendum that the mixed-race couple has experienced xenophobia on London’s streets. “It was a group of people, outside a pub in Islington, chanting things ... but honestly, [Brexit] hasn’t affected us. If anything, it’s made us stronger. We just really believe in what we do.”

She’s buoyed by women such as Saffiyah Khan, the smiling, EDL-defying protester who went viral after a Birmingham rally. “That image just said it all, didn’t it? I feel optimistic. I cope with [the strife] by doing this work.”

If she’s uninterested in overtly political lyricism that is perhaps because her values are self-evident in her work. “Its clear where I stand. I’m trying to create aspace where Ican bridge worlds, not keep themapart.”

It’s a practice that speaks to the cultural appropriation debates raging in mainstream pop culture — debates Raman doesn’t keep up with. “I’m committed to the idea of unity, especially now, when there are so many forces trying to [divide us]. It doesn’t mean you pretend everyone is the same — there will be contradictions and complexities, but I think celebrating our commonalities [is vital].”

Extremism of all kinds should be resisted, says Raman, from the US’s cross-burning fascists to the institutional Islamophobia she has witnessed under India’s Modi government. Sacred Imaginations is, subconsciously, part of that resistance — a chance for a diverse audience to experience unity and transcendence collectively, through music. “We hope we can share some of the beauty, intensity and rapture of sacred music [freed from] dogma.”