From variety hours to talk shows to dedicated specials, stand-up comedy on television is just about as old as television. Millions (I am guesstimating) who have never seen a comic work a nightclub or theatre have seen dozens upon dozens of them on TV. Some of these people decide to become comedians themselves.

“When I was a kid and a comedian came on TV, I would just freeze and stare at them,” Jerry Seinfeld remembers in Jerry Before Seinfeld, a dedicated special on Netflix, which has been investing heavily in stand-up comedy, big-name and littler-name alike.

Jerry Before Seinfeld is the first expression of a deal ($100 million, or Dh367 million, is the bruited figure) that also brings the network past and future episodes of Seinfeld’s drive-talk-and-drink series Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee.

HARSHER APPROACH

Its long history with the medium notwithstanding, stand-up doesn’t always work on the screen. There are wrong ways to film it — poor camera placements or post-production varnishes that can alienate the viewer, that kill a sense of shared space and spontaneity every comic seeks to create. There is nothing television can do to make a bad comic funny, but it can make a good performance feel inert. I approach such programmes hopefully, with trepidation. I want to laugh but know I might not.

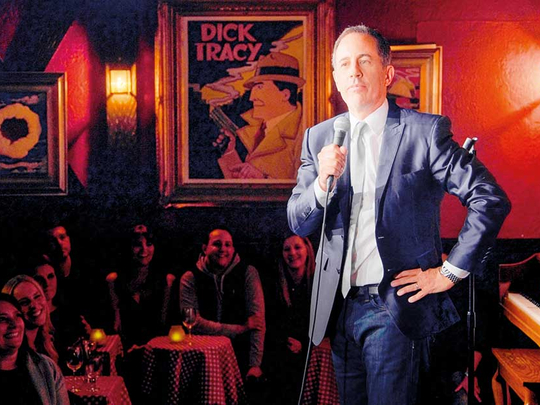

I laughed a lot during Jerry Before Seinfeld, in which Seinfeld returns to the stage of the Comic Strip, the New York comedy club he worked for no money and many hamburgers while getting his act together in the 1970s. Much of the material he performs here predates the series that took his name and magnified it: Seinfeld, which translated a comic’s obsession with life’s illogical annoyances into a world-conquering situation comedy.

It’s an interesting and novel approach for a comedian, something like when singers in their later years — Frank Sinatra or Joni Mitchell or Elvis Costello — revisit songs recorded in younger ones to find different shadings in a different register. Experience seasons innocence. Seinfeld’s new attack on his early material has a different music and energy. The young man bemused by the absurdities of civilisation comes on now like a comic who is now harsher and hoarser and invigorated with age.

“I grew up in the ‘60s,” Seinfeld tells the crowd, going on in an increasingly mocking tone, “and I see a lot of beautiful young people here tonight enjoying your life of infinite potential and opportunity because you’re young and your life is still ahead of you and it’s all gonna to happen. Let me tell you little punks something.” And he does.

REVISTING HISTORY

With documentary interludes recalling the comic’s early life; it’s like a compact version of an autobiographical one-man show. Here is Seinfeld on the steps of his childhood home, surrounded by childish things. Here he is sitting in 57th Street and Madison Avenue, where he used to eat lunch in the days he worked a construction, or destruction, job a couple of blocks away; here he is in the middle of what looks like a West Village residential street, sitting in a sea of legal-pad pages containing every good joke he’s written “from 1975 till this morning”.

“I only had one joke that worked, which I’m going to do for you right now. And if you ever think you yourself might someday want to do comedy, this is not the way you do it. Don’t ever say, ‘I’m going to do a joke now’.” It’s a joke about left-handedness. His second good joke, about a roller coaster in the South Bronx, he tells too.

Seinfeld recalls his parents coming to see him work for the first time, pointing out just where they sat. “For whatever reason I was very embarrassed around my parents to show them this part of my personality ... . It was like my little closet moment. ‘I’m a funny person, and I don’t want to be ashamed of it anymore, and I want to lead a funny lifestyle now. I want to be with other funny people. I want to have breakfast at 2 in the afternoon’.”

The stand-up material is a mix of reminiscence and more abstract ideas such as, “I always like that whatever goes on in the world, it somehow exactly fits the number of pages that they’re using in the paper that day.” (You can tell that’s an old joke.) Wondering if a stun gun could be adjusted “so you were just taken aback”.

Picturing clothes as “waiting all the time. ... Everything you’re not wearing right now is hoping to get picked tomorrow”, but that “socks hate their lives” and are always looking to escape.

“To feel that your sense of humour is actually being validated,” says the comedian, “that is the only validation I think I’ve ever really cared about as a human being. But I didn’t ever really care about whether they liked me or not ... it was, ‘Do they like the material?’

“I wasn’t really planning on getting anywhere doing this, by the way,” he admits.

But stuff happened.

Don’t Miss It!

Jerry Before Seinfeld streams on Netflix.