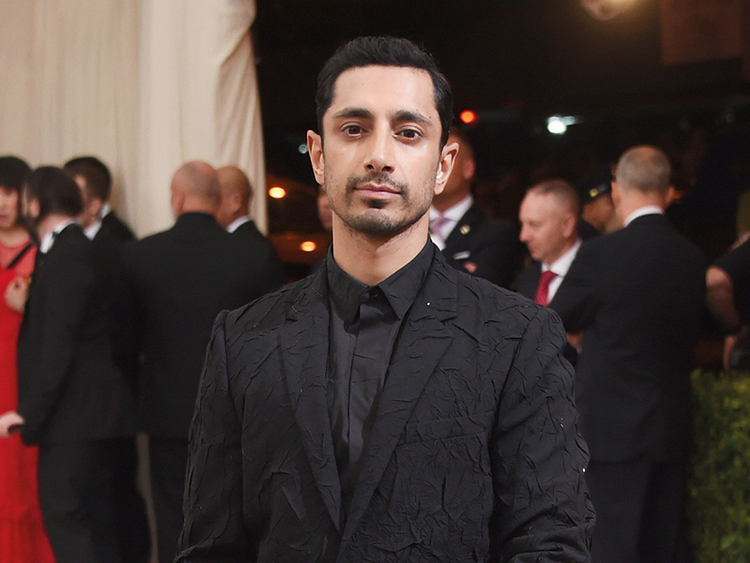

US culture has a new mantra: it’s down with brown. In the past few years, entertainers of south Asian origin have gone from being a minor footnote in American popular culture to a headline event. You can see a snapshot of this new America in a picture British-Pakistani actor Riz Ahmad tweeted this month at the Met Gala, the annual gathering of pop-culture royalty. Captioned “Taking over the #metgala2017”, it showed Ahmad standing next to comedians Mindy Kaling, Aziz Ansari, and the Daily Show’s senior correspondent, Hasan Minhaj.

South Asians aren’t just taking over the Met Gala, they’re popping up everywhere. Last month, Minhaj headlined the annual White House correspondents’ dinner. In April, Ahmad was one of the cover stars for Time magazine’s list of the 100 most-influential people in the world. And Kaling and Ansari are both first-generation Indian-Americans who have created, written and star in major TV shows — The Mindy Project and Master of None, respectively. There’s also Kumail Nanjiani, who plays the leading man in The Big Sick, a romcom produced by Judd Apatow, which comes out in July. Not to mention Oscar-nominated Dev Patel, Priyanka Chopra, who plays an FBI agent in Quantico, and Archie Panjabi in The Good Wife. In music, there’s Vijay Iyer, a first-generation Indian-American who is one of the most famous living jazz musicians in the world. There’s Zayn Malik who is, perhaps, the most famous Bradford-born Muslim to quit a boy band in the world. And that’s without mentioning Ahmad’s musical side project, Swet Shop Boys, or Brit-Sri Lankan rapper MIA, whose south Asian identity politics have played out on the blogosphere since her first release in 2003.

If you’re British then this sudden surge of brown faces on US screens may seem a little been-there-done-that. After all, the relationship between Britain and south Asia goes all the way back to the founding of the East India Company in 1600 and, you know, that whole colonialism thing. South Asians have played a significant part in British culture for a while. Hell, even Britain First supporters go out for a curry.

But things are very different in the US, where south Asians make up a far newer, far smaller percentage of the population and have traditionally occupied little, if any, space in the national consciousness. You can see this reflected in the different nomenclature: in Britain, “Asian” refers to south Asians; in the US, it refers to east Asians. South Asians are a subgroup of a subgroup. It is not an exaggeration to say that, for decades, the most famous south Asian in the US was Apu Nahasapeemapetilon, proprietor of the Kwik-E-Mart in The Simpsons. And not only is Apu a cartoon character, he’s voiced by Hank Azaria, a white man.

Indeed, for a long time, if there was a south Asian in a US production, chances are that it would be a white guy in brownface affecting a “hilarious” Indian accent. Peter Sellers, for example, plays Hrundi V Bakshi, a bumbling Indian actor, in the 1968 movie The Party; Azaria has said that he based Apu’s accent, in part, on Sellers’ performance. In Short Circuit 2, a 1988 comedy about a robot who befriends an Indian scientist, the Indian is played by Fisher Stevens (“They got a real robot and a fake Indian,” Ansari jokes in one episode of Master of None). Don’t think we left the brownface behind when we entered the 21st century. Divya Narendra, an Indian student in the 2010 movie The Social Network, is played by Max Minghella, who is decidedly not-Indian. And, in 2012, a Popchips advert featured the very white Ashton Kutcher impersonating a Bollywood producer.

South Asian actors are still asked to do accents and play stereotypical roles. This year, Kal Penn (of Harold and Kumar fame) shared some of the audition scripts he was given at the beginning of his career. These demanded an accent and were for roles such as “Gandhi lookalike”, “snake charmer” and perspiring “Pakistani computer geek”.

In a 2015 essay for the New York Times, Ansari recounted similar experiences: “Even though I’ve sold out Madison Square Garden as a stand-up comedian and have appeared in several films and a TV series, when my phone rings, the roles I’m offered are often defined by ethnicity and often require accents.”

It should be noted that the “perspiring geek” stereotypes and fresh-off-the-boat accents tend to be reserved for men: south Asian stereotypes tend to emasculate the men and eroticise the women.

Stereotypes don’t just affect the sort of roles south Asians are offered, they have an impact on the way that south Asian creativity is parsed. In a profile in the New Yorker, Iyer notes that: “Critical writing used to attempt to place me by othering me, by putting me outside the history of jazz. Everything I did was seen as different and not as the continuity of a tradition. Critics never describe black music as rigorous or cerebral or mathematical, although [John] Coltrane was interested in mathematics. Since I was Asian, I was seen as having only my intellect to use.”

Why have these stereotypes gone relatively unchallenged for so long? When the Popchips ad first aired in 2012, blogger Anil Dash wondered how the American media could be blind to the “obvious offensiveness of this campaign”. Dash pointed out that both the New York Times and the Washington Post covered the campaign “with no note of how obviously offensive the featured ad is... It’s astounding that this wouldn’t be obvious on first glance to those who are paid to understand media and culture.”

The reason it wasn’t obvious, perhaps, is because 99 per cent of those who are paid to understand media and culture in elite American media come from homogeneous white backgrounds. But, explains Shilpa Dave, assistant professor of media studies and American studies at the University of Virginia, another reason may be that “south Asians have always been in an ambiguous racialised space in the United States”. In the early 20th century, south Asians were thought of as white in the US. This changed in 1923 when a court ruled that they were “Asian others” and aliens — something that had huge ramifications, as it meant they were unable to become naturalised citizens. “So, they’re one of the only groups who had citizenship and then had it taken away,” Dave notes. “That ambiguity has followed how south Asians have been characterised in the United States.” They’re not quite white, but they’re not as other as African-Americans. Which means that making fun of south Asians isn’t seen as full-blown racism.

In her book Indian Accents, Dave looks at the racialisation of south Asians through what she terms “brown voice” in American TV and film. “An accent highlights the norm... and it also points out its own difference,” she says. An accent piece of furniture, for example, acts as a complement and contrast to the rest of the furniture in the room. Dave hypothesises that Indians have worked as a sort of accent piece in popular culture; an exotic set decoration that spices things up without being too threatening. “The way Indians function in representations of Hollywood is oftentimes as an acceptable form of difference. Yes, they are different, but it’s a difference that we can accommodate.”

US immigration policy has also been very clear about the sort of difference it is willing to accommodate. While south Asians have been emigrating to the US for more than a century, they didn’t start arriving in large numbers until the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965. This allowed far more immigrants from south Asia into the US than before (previously, 70 per cent of all immigrant slots were allocated to people from the UK, Ireland and Germany), but gave preference to people with medical and science backgrounds.

Pawan Dhingra, professor of sociology and American studies at Tufts University, explains that this meant “many of the south Asians who came in the ‘60s, ‘70s, even the ‘80s, were of a relatively finite number of occupations. They came as physicians or engineers and then, later, as computer scientists.” This helped create a self-perpetuating stereotype of south Asians being doctors and engineers. “It’s very common, regardless of your ethnicity, for children of people in these kinds of occupations to continue in these occupations,” says Dhingra. Demographics, then, are one reason why we’re starting to see more south Asians in American popular culture. South Asians have been in the US long enough to have children who have broken through into creative professions.

Perhaps more importantly, we’ve also got to a point where south Asians aren’t just starting to get a seat at the table, they’re criticising the seating arrangement. Ansari, for example, has brought issues of representation and racism directly into the plotline of Master of None. Indeed, there’s a whole episode in the first season called Indians on TV, which begins with a montage of how Indians have been represented — ranging from monkey-brain eaters in Indiana Jones to Zac in Saved By the Bell making jokes about 7-Elevens in a fake Indian accent. Ansari’s character, Dev, then finds himself grappling with the difficulties of trying to push back against these stereotypes while still making a living as an aspiring actor. He refuses to do an accent for the role of “Unnamed cab driver” on a TV show, for example, and doesn’t get the part. His friend Ravi goes up for the same part and does an accent. “I think about [stereotypes], too,” Ravi tells Dev. “But I’ve got to work.”

Minorities can often feel a pressure to shut up and put up with things and avoid being seen as an Angry Ethnic, if they want to get ahead. A pressure to be a subservient “Uncle Taj”, as Dev puts it on Master of None. And it’s fair to say that for a long time, south Asians haven’t been particularly vocal about critiquing the racial divide in the US. After all, it’s a racial divide that’s traditionally been very black and white — with south Asians grudgingly being allowed to stand on the white side if they behaved themselves and didn’t draw too much attention to their otherness.

September 11 changed all that. Suddenly, it didn’t matter if you were Indian, Sri Lankan, Pakistani, Hindu, Sikh or Muslim — after 9/11, being brown meant being a potential terrorist. The response to 9/11 has created a generation of highly politicised south-Asian Americans who are pushing back against the model-minority label and finding new commonality with black America. As Ahmad raps on the Swet Shop Boys album: “My only heroes are black rappers / So, for me, Tupac was a true Paki.”

This politicisation is particularly marked now, with Donald Trump in charge and hate crimes against south Asians spiking. Anupama Jain, the author of How to Be South Asian in America and a teacher at the University of Pittsburgh, says she feels that “there is a widespread raising of south Asian consciousness” at the moment. Her south Asian students are reaching out to her, saying: “People are killing south Asians right now,” and asking what they should be doing. Entertainment has become one way of doing something. Minhaj, for example, did not mince his words at the White House correspondents’ dinner — something that clearly made the largely white crowd quite uncomfortable. A sample joke: “As a Muslim, I like to watch Fox News for the same reason I like to play Call of Duty. Sometimes, I like to turn my brain off and watch strangers insult my family and heritage.”

In these Trumpian times, the high-profile success of so many talented brown people is a truly heartening thing. However, it’s worth remembering that progress isn’t necessarily linear and that the prominence of minority narratives is often cyclical. In the UK, for example, there was a boom in British-Asian culture in the ‘90s; shows such as Goodness Gracious Me were mainstream entertainment and Cornershop’s Brimful of Asha was No 1 in the charts. But, as Ahmsd and actor and comedian Meera Syal have recently pointed out, ethnic-minority representation on British film and television is at its lowest point since the early ‘80s. Let’s hope what we’re seeing happen in the US is more long-lived.

Digital media has also helped give a new generation of south Asians a chance to share their stories without establishment approval. Rather than be subject to traditional gatekeepers, desis are doing it for themselves. Last year, Canadian-Indian Lilly Singh — who goes by IISuperwomanII online, was the third-highest-paid vlogger on YouTube (and the highest-paid female), earning a reported $7.5 million (Dh27.5 million) in 2016 with videos such as The Rules of Racism, and When a Brown Girl Dates a White Boy. Now, more south Asians are hoping to emulate her success. Krishna Kumar, a 26-year-old YouTuber, explains: “When someone tells us no, we can still say yes to ourselves.” Kumar is, with his friend Kausar Mohammad, currently working on a parody of Ariana Grande’s Dangerous Woman music video called Dangerous Muslims. The video is an open letter directed to Trump, which the pair hope will help dispel fear about Muslims. “I’m a strong believer that artistic expression is a strong catalyst of social change,” Mohammad says. “Comedy comes from a place of hurt often. You either laugh about it or cry about it.” Like many minority comedians before them, they’re choosing to laugh.