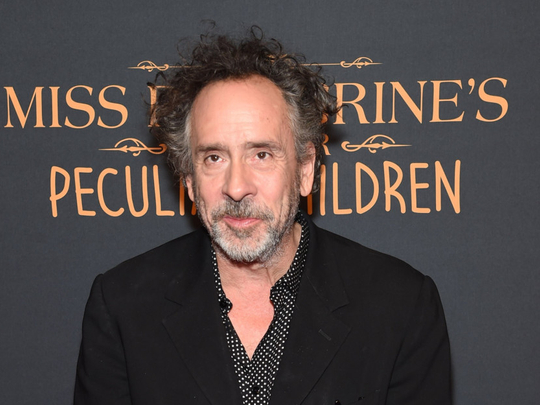

Apparently, director Tim Burton would be fine if you retitled his movie Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children but Only if They’re White.

In an interview with the website Bustle, Burton was asked why, given the pervasive, ongoing discussion of diversity in Hollywood, the overwhelming majority of the characters (and, hence, actors) in his latest fantasy film are white.

“Nowadays, people are talking about it more,” Burton said. But “things either call for things, or they don’t.”

He went on to talk about how, as a kid, he would’ve been dismayed to see an Asian kid or a black kid on The Brady Bunch, or more white actors in blaxploitation movies. (Never mind that there were white actors in blaxploitation films, but more on that later.)

Burton’s statements are just the latest from a celebrated, veteran filmmaker unable to wrap his mind around why diversity matters.

Ridley Scott, when discussing the casting of white actors to play characters of Middle Eastern and North African descent in his Exodus: Gods and Kings, told Variety: “I can’t mount a film of this budget, where I have to rely on tax rebates in Spain, and say that my lead actor is Mohammad so-and-so from such-and-such. I’m just not going to get it financed. So the question doesn’t even come up.”

And, of course, there was a logic to Scott’s statement, just as there is some to Burton’s. You need a movie star to make a $150-million (Dh550.5-million) biblical epic feasible, so you get Christian Bale. No one faults him there. But there is no reason why Seti, a pharaoh of Egypt, needs to be played by John Turturro doing a bad Britishy accent. None.

Mirror the population

The majority of the action in Burton’s Miss Peregrine’s takes place on an island off the coast of Wales during Second World War. In Burton’s view, apparently, this fantastical school for fantastical children needn’t be burdened with having to mirror the population of the United Kingdom at that time — which boasted millions of people born abroad, from places like India, Jamaica, Pakistan and various African countries. Not a huge percentage of the population, mind you — according to a 1951 census, 4.2 per cent of the total UK population — but enough.

And that’s not considering the native-born people of colour whose ancestors had emigrated to Britain, either by choice or by force, since the 16th century and became part of the fabric of British society.

In Burton’s case, the reasoning clearly wasn’t financial: The Harry Potter filmmakers cast their magical British refuge with actors with every skin tone one might encounter in Trafalgar Square. And no one blinked on their way to Gringotts with the $7.7 billion those films grossed. Nor did Potter creator J.K. Rowling blink at the idea of a black Hermione for the stage production of Harry Potter and the Cursed Child.

Of course, period adaptations can require a certain fidelity to the source material ... except for when they don’t. The BBC produced a version of Oliver Twist that cast actors of colour in major roles and was well-received (and Dickens didn’t curse anyone from beyond the grave).

And, you know, Hamilton.

Villain

But fantasy allows for anything under the sun. There are no rules apart from the rules that makers of fantasy set for themselves.

“Things either call for things, or they don’t.”

The only character of colour in Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children is Samuel L. Jackson, who plays the film’s villain, Barron, who kills kids with these special powers. In fact, as Rachel Simon, who wrote that Bustle piece, points out, Jackson is the first black actor to land a leading role in any of Burton’s 36 feature films.

As I’d mentioned before, in the blaxploitation films that Burton claims to have watched growing up, there were white actors — they just always played the bad guy, the heel, The Man. The inverse appears to be true for Burton films: If you are to encounter a black actor, he’s either going to be in the periphery (Billy Dee Williams in Batman), slathered in make-up (Michael Clarke Duncan in Planet of the Apes) or he’s going to be the bad guy.

Burton’s heroes are always versions of himself: thin, pale, white outcasts. From Edward Scissorhands to Ed Wood, Alice in Wonderland to Willy Wonka.

A filmmaker is allowed his or her perspective on the world. That’s what makes them unique. Just as we, the audience, are allowed to wonder why, in his mind, the only colour an outcast hero can be is white.

Burton’s hallmark as a director is, and always has been, his imagination, his vision. It is sad to discover that, in this regard, he has neither.