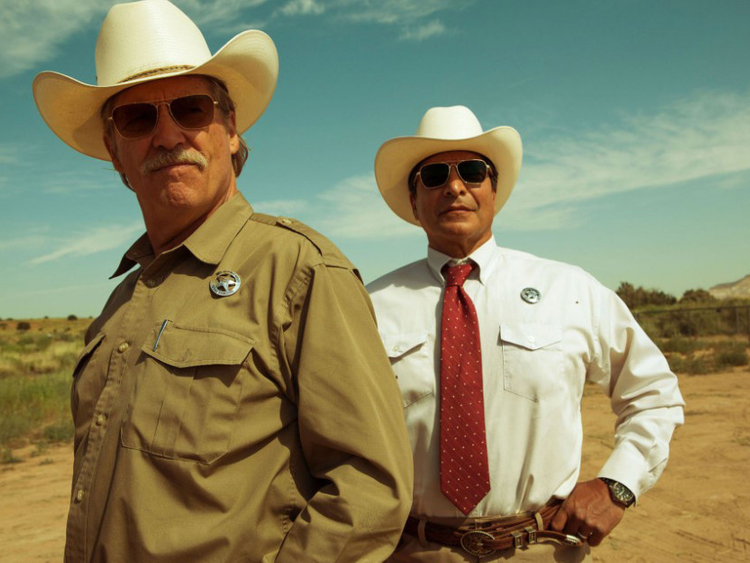

For a budding screenwriter, Taylor Sheridan has certainly hit the ground running. The square-jawed former actor, best known for playing a straight-arrow lawman on the FX series Sons of Anarchy, made a splash with his first screenplay for the 2015 drug-war thriller Sicario. His next film, Hell or High Water, which opens in the UAE on September 1, is the story of soon-to-retire Texas ranger Marcus Hamilton (Jeff Bridges) in pursuit of two bank-robbing brothers (Chris Pine and Ben Foster). Critics have praised the film, which is set against a backdrop of home foreclosures, for its grit and social consciousness.

The 47-year-old’s directorial debut, Wind River, is due out next year, and his Sicario sequel, Soldado, begins shooting this autumn. Sheridan spoke recently about the social relevance of his film and his successful move from screen to page.

How did you make the leap from actor to screenwriter?

I made a very conscious decision to quit acting. I was on a series and we were in the process of renegotiating. They had an idea of what they thought I was worth, and I had an idea that was quite different. My wife was pregnant. I wasn’t a movie star. People have a misconception of what a journeyman actor makes — not a lot of money. You can maybe make 150-grand [Dh550,809] a year before taxes on a show like that. You can’t get rich.

Some would say that screenwriting isn’t exactly a road to riches either.

Look, if you want to get rich, sell Learjets. There are a lot easier ways to make money. It really came down to telling stories, and I wanted to tell my own. My situation made it easy for me to go, ‘Well, maybe that is what I’m worth, as an actor.’ At least I’m not telling someone else’s story.

There are some heavy political themes — gun rights, racism, the home mortgage crisis — baked into the plot of Hell or High Water. Why are you interested in such hot-button issues?

I wanted to do things that I thought were socially reflective and that made people ask questions about issues. There’s such a divisive society now. It’s like there are two Americas. I just wanted to explore the world I know, because I’m from Texas. My family had a ranch an hour west of Waco that we lost in 1993, as the casualty of a divorce. I’m acutely familiar with what that feels like. I witnessed my mother suffer by drinking the Kool-Aid with some of these loans. But I wouldn’t call them political issues. I’d call them social issues. I’m just trying to hold up a mirror to the world.

You’ve said, ‘If anyone can understand my politics, I’ve failed.’ What did you mean?

I’m in a business that seems to think it knows best, and we have a pretty alarming amount of power to speak without being interrupted. I try hard to only ask questions and to do it in an entertaining way.

But Sicario and Hell seem designed to rattle viewers, as well as entertain.

Shouldn’t movies rattle you? I have a hero in Marcus, whose affection for his friend [Alberto, a Native American Texas ranger played by Gil Birmingham] can only be expressed through insulting him and choosing the most superficial and harmful insults to do it. Does that make him an evil man? He seems like a pretty good guy, but he says some pretty rotten stuff, which I think is pretty representative of man as a whole.

Sicario was noted for its unconventional five-act structure and shifting protagonists. Aren’t screenwriting rules there for a reason?

I see them more as guidelines than rules. As a television actor, I was held to a tight, rigid structure. A lot of it was childish rebellion. I sat down to write a script, and I thought, ‘I’m going to break all these rules I’ve been held to for so long’. When I was working on Sicario, I realised how rule-breaking alters the expectations of the audience, how it changes the journey. It makes it feel like you don’t know what’s going to happen next.

What did you bring to screenwriting from your acting career?

You only have to look at my resume to know that I wasn’t doing groundbreaking work as an actor. I paid the bills. I worked on largely procedural network shows, and then I did some really small, really bad movies, and auditioned for thousands more. I don’t know how many scripts I’ve read in my life. When I sat down to write Sicario, I had to be humble and honest and say, ‘You have no idea how to do this, but you certainly know how not to.’

How does the idea of the West inform your work?

All of my films are explorations of the modern American frontier. As a boy, I was fascinated with the West and cowboys and trappers. I became fascinated with Native Americans who were there, who we took it from — those battles and that assimilation and the consequences of that. It’s been romanticised and vilified and glossed over. Looking at the consequences of American expansion is really fascinating to me. How much has the frontier changed in 150 years? How much has it not changed?

There’s a great line in Hell where an old codger remarks that the good old days of robbing banks and living long enough to enjoy the money are long gone. Where does that nostalgia for lawlessness come from?

There’s a real sense of freedom in the West. Some of the resistance to dealing with contemporary social change is because of a sense that real freedom is being taken away.

Is it possible that this sense of freedom is an illusion?

There was a time in the late 1800s when you were pretty free to do whatever you wanted. You were free to die of starvation. You were free to be attacked. It was total freedom. But I think it’s more a notion, a sense that you can effect change. When the old-timer says that, he says it as if we’ve reached a place where you can’t really effect change anymore. It’s ironic that it’s applied to a moment of theft. It’s a romantic — not intellectual, not logical — parallel that he’s drawing.

The director of the new film, David Mackenzie, is Scottish. Denis Villeneuve, who directed Sicario, is French Canadian. Were you concerned about non-Americans directing quintessentially American stories?

I think because they are not Americans, they see things that we don’t see because we are so used to seeing them that we don’t notice anymore. They’re also not tethered to an opinion on our politics. They’re not personally invested.

The character of Marcus, who’s being forced to retire, was inspired by your uncle Parnell McNamara, a former US marshal and old-school lawman. What about him interested you?

He was a federal marshal for 30 years and very capable. One day he is knocking down a door arresting some drug dealer, and the next day he’s got a letter saying, ‘Turn in your badge and your gun.’ I thought that the notion of suddenly having your purpose in life taken away from you was really fascinating.

Both of your screenplays are extremely violent. Yet you’ve called Sicario a meditation on the rule of law, and you describe Hell as a love poem to Texas. Where is that love poem, beneath all the bloodshed?

You see that love poem in the ancillary characters, in the sort of Greek chorus of people that you meet as Marcus and Alberto move through west Texas. The film is really a meditation on failure. It’s a study of morality as well, of the shifts that take place in you as you change your mind about the things that you think are okay or not okay. I explore that, in an extreme way.