Technology, especially the internet, has changed the way we experience culture, and Australian Aboriginal art hasn’t been left untouched. Having remained largely confined to specific communities and niche galleries in the country, it has slowly been making its way into the global mainstream and finding patrons across the world. In fact, just last June, a collection of 75 rare pieces of indigenous art went under the hammer for the first time at Sotheby’s London and sold for a record $2 million (Dh7.3 million).

Tim Klingender, Senior Consultant of Australian Art to Sotheby’s London, and the specialist in charge of the sale, told ABC News he was thrilled with the results. “It was a bit of a risk to put on a sale of Aboriginal art outside Australia. I wondered whether there was enough global interest to support it, but I was absolutely astounded by the results and the market and the bidding.”

While indigenous art in Australia dates back about 60,000 to 80,000 years and is among the oldest art traditions in the world, its contemporary face is multidisciplinary, encompassing everything from watercolours, landscapes and dot painting to photographs, mixed-media installations, woven works and sculptures that proliferate galleries and shows. These draw from a powerful heritage — the outback has been home to thousands of Aboriginal artists who have depicted stories of life and civilisation on rock or tree bark, created carvings, painted aerial landscapes (which often tell traditional Dreamtime stories), or woven dreams in fibre.

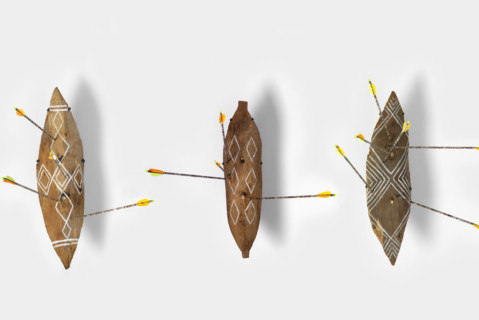

Take, for instance, the exhibition Murruwaygu: Following in the Footsteps of our Ancestors, which runs until February 21 at the Yiribana Gallery, part of Sydney’s Art Gallery of New South Wales. It is a tribute to the Koori community of more than 100 language groups of south-east Australia, creating a kind of cultural memory. “It traces the use of line across four generations of Koori artists,” indigenous installation artist and curator Jonathan Jones says in notes.

“Analysing its continuous use through significant social, political and cultural change, [the exhibition] reveals an enduring cultural tradition of great importance.”

A variety of wooden shields, such as marga and the manggaan, works on paper, paintings and video art are included.

Contemporary heritage

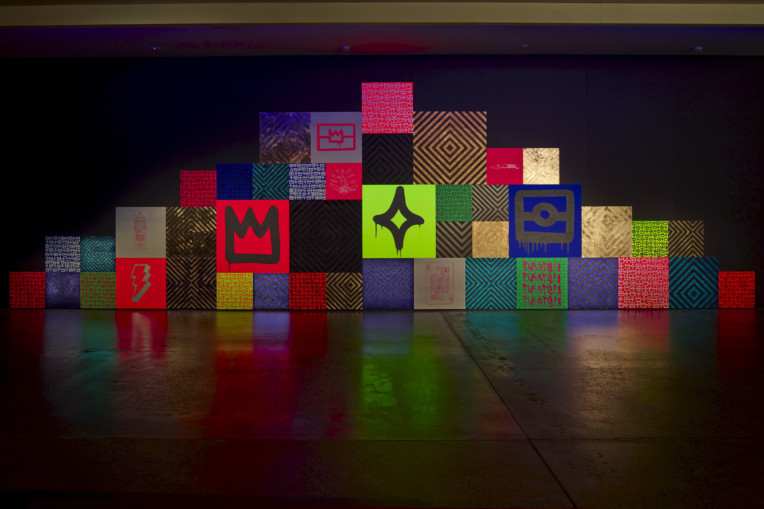

A large section of indigenous artists still work with traditional forms, but many new age ones are pioneering technology-infused work, which still evokes a sense of tradition while preserving their heritage. One such artist is London-based Christian Thompson, widely regarded as one of Australia’s most prominent contemporary indigenous artists. “Indigenous art in Australia is dynamic, ancient and diverse,” he tells GN Focus.

“I’m interested in where culture can go, how we can embrace traditional ideas and practices and bring them into the now.” Thompson recently completed his PhD in fine art at Oxford University and is the first Aboriginal Australian ever to be admitted to the institution. His work is everywhere, from Cate Blanchett’s home to the National Gallery of Australia, and he even exhibited a photo series — The Other and Me — in Sharjah in 2014.

Thompson’s art — photographs, sculptures, music and performances — is deeply rooted in the way he interprets his indigenous identity. His father is Aboriginal and his mother is of English descent, with ancestors from Australia’s colonial past.

“I have a rich genetic history,” he says. “I also had a very traditional Aboriginal upbringing in the bush, eating bush food and speaking our language [Bidjara].”

The results are visible in video installations such as Dead Tongue or Refuge, in which Thompson performs songs that he’s written himself in pigeon Bidjara — he wanted to use traditional songs, but his father told him there aren’t any left — but made contemporary by the use of pop tunes.

Most people don’t understand the language, and Thompson is happy to allow individual interpretations. “I am not trying to teach people my language but present it in a form in which it can be enjoyed and in a way that demonstrates its innate lyricism.”

Inspired by the land

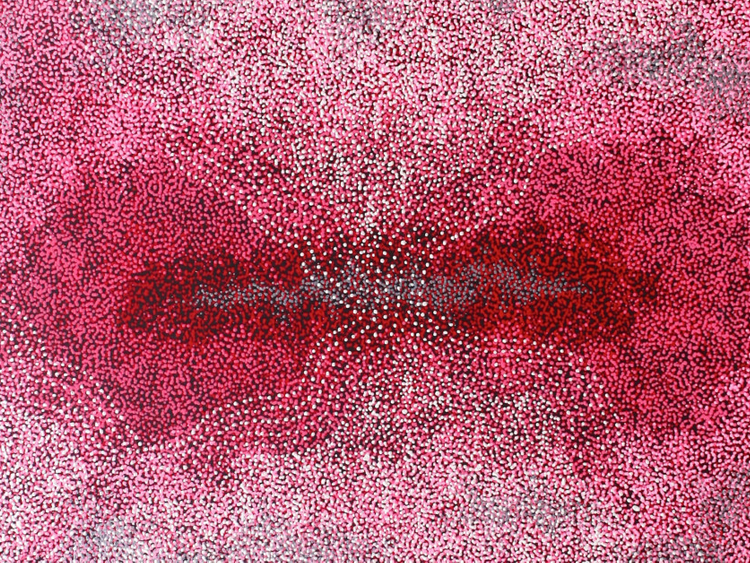

For Tarisse King — daughter of acclaimed Aboriginal artist William King Jungala (from the Gurindji tribe in the Northern Territory) and sister of artist Sarrita King — indigenous art is a language of her people and an important part of passing down and preserving their stories over the generations. A landscape painter — her most popular works include Pink Salts and My Country — Tracks and Rivers — she draws primary inspiration from the dotting style of painting and creates canvases of Australia’s various climates and topographies.

“Using the techniques my father taught me, I paint the land how I see it in my mind: beautiful, perfect and vibrant,” the 28-year-old artist, who lives in New Zealand with her two daughters, tells GN Focus. “I have taken my favourite surroundings and painted my interpretations of them.

“I was lucky enough to grow up in beautiful, tropical Darwin. So, looking at my Elements series, for example — especially the Bush paintings — you can tell they are directly influenced by the wet season in the Northern Territory.”

While she mainly exhibits in Australia, a lot of her artworks have found their way overseas, where people connect with their stories and colours.

Galleries such as Kate Owen and Kununurra-based Artlandish Aboriginal Art Gallery have gained international renown for the collections and artists represented online, their superior quality, authenticity and price. Tapping into social media platforms such as Facebook has helped boost sales, as well as spread the word.

“It’s been astronomical, the level of engagement we’ve had,” Scott Linklater, manager of the 15-year-old gallery, told CNN.

During one sale that took place a few months ago, 13 paintings were sold directly through Facebook.

“It may be one of the oldest art forms in the world, but it’s one of the youngest genres of the art market,” Linklater added. “If you’re prepared to hold on to the art for five to ten years, it represents great value.”