In 1943, the Uruguayan artist Joaqun Torres Garca turned the world upside down. His Amrica Invertida, or Inverted Map of South America, is a simple ink-on-paper drawing that puts Caracas at the bottom and the south pole at the top. The south becomes the north. After centuries of condescension (the north Europe, the US assumed to be more important than the south), Latin America’s importance was deftly reclaimed. Thanks to the map, the artist wrote, “we have a true idea of our position, and not as the rest of the world wishes”.

Torres Garca was determined to establish a distinctive and confident art movement in South America. In many ways, the excellent, eye-opening Radical Geometry at the Royal Academy sets out to do the same. It makes the case that the different kinds of abstract paintings and sculpture produced in Uruguay, Argentina, Brazil and Venezuela from the 1930s to the 1970s were as innovative as anything being attempted in the “north”. Most people, if asked about Latin American art, think of the Mexican muralists and Frida Kahlo’s self-portraits; this show offers a rich alternative.

The exhibition arrives at a good time as several of the show’s standout practitioners are being talked about as never before. The Venezuelan Gego, best known for her delicate, three-dimensional wire works, is increasingly feted, as is the Brazilian Lygia Clark, whose 1960s sculptures, Creatures, designed to be picked up and folded into different shapes, have been an attraction in a recent, warmly welcomed MoMA retrospective. Along with the intriguing Inca-inspired pictographs of Torres Garca and the approachable, agitated grids of Hlio Oiticica (who also designed geometrically patterned capes “habitable paintings” for samba dancers), the work of these artists will surprise sceptics expecting stale variations of European modernism, or non-aficionados understandably wary of such labels as concretism and neoconcretism.

Thanks to the recognition now given to Clark, Gego and others, if the world hasn’t been turned upside down, it has at least been tilted. It was a very different situation the first time many of the Radical Geometry artists were shown in Britain at the landmark Latin American show put on by the Hayward in 1989. The critic Tim Hilton reviewing the exhibition remarked sniffily that “no group and scarcely one individual artist attains the high and continuous creativity we expect from admirable art”, while Brian Sewell commented that the continent’s art was no more distinguished than the painting on Turkish donkey carts. Such views seem embarrassing now.

So the Royal Academy show, curated by Adrian Locke and Gabriel Prez-Barreiro, has no need to be defensive. It tells four main stories, each involving a different country in a particular era. All the art displayed was propelled by radicalism of differing kinds, all more or less political as abstraction swept through South America. In the catalogue, Locke elegantly introduces the economic and political contexts of the four radical moments. Montevideo was a modern capital with wide boulevards, parks and intellectuals gathering in coffee houses; Buenos Aires was “a cosmopolitan city of grandeur and sophistication”. Brazil made itself a global art-world capital in the late 1940s and 50s with new galleries and the Sao Paulo biennale — the big Brazilian cities were hot centres for abstract painters, not in a provincial sense, but internationally. In prosperous Venezuela, the modern art movement, influencing industry, science and architecture, also made political sense: it helped the country appear vibrant and in vogue. The continent was a destination shining with promise, chosen by many European immigrants over the US. An interchange of ideas across the Atlantic between Europe and South America — one that has so often been written out of art history — was inevitable.

The first of the four stories concerns Torres Garca, who spent decades in Europe before returning to Montevideo in 1934. In Barcelona, he painted murals for Antoni Gaud; in Paris, he mixed with Joseph Stella, Marcel Duchamp and Joan Mir, and produced winning cityscapes. But his most recognisable work seems to have arisen from two particular influences — an intense interest in Latin American culture preColumbus, and the compositions of Piet Mondrian.

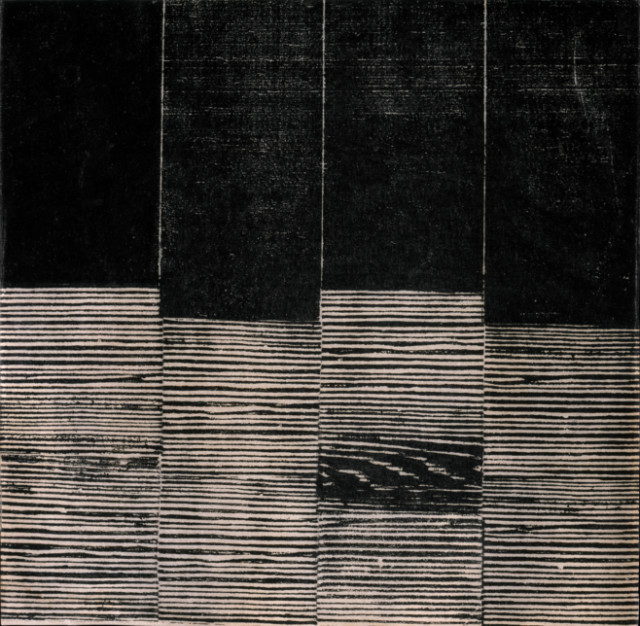

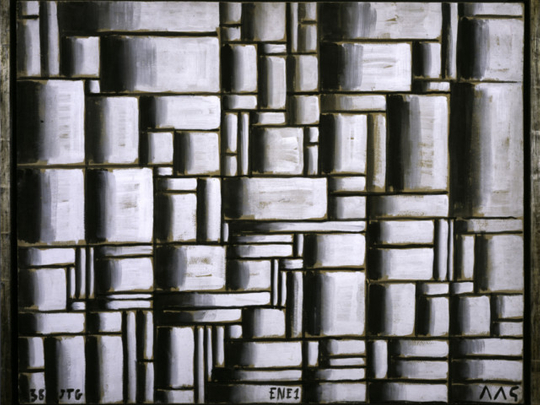

The results were his 1930s grid paintings in earthy colours of box-like compartments, variously sized, almost like a chic wall-storage system: an example in the show is Construction in White and Black. The pattern suggests Inca stone work, with regular-shaped blocks cleverly fitted together. In other works the boxes contain child-like “signs” a fish, a clock, a face, a wheel, a boat, the sun. Torres Garca began a movement, utopian and democratic in spirit, that argued for geometry as the key to all art, and sought to incorporate pre-Hispanic ideas, in the belief that simple symbols could be understood regardless of the viewer’s background. The divide between “high” and “low” art forms would disappear — art would be accessible to the masses.

To spread his ideas, he had a radio show, delivered lectures and founded a school, rather like the Bauhaus. As Prez-Barreiro explains in the Radical Geometry catalogue, Torres Garca believed that “an artist should craft a coherent lifestyle and environment as a prototype of a new social model”. Such a cause needed disciples, and his “Studio of the South” flourished, at least for a while.

Definitely not among his faithful followers was a group of young revolutionary artists from across the Ro dela Plata, in Buenos Aires, who populate the second story of the exhibition. For GyulaKosice, Ral Lozza and Toms Maldonado, in the mid-1940s, Torres Garca’s art was not universal and spiritual but dusty and rather fey. They regarded abstract art as, according to Prez Barreiro, “an urgent response to a primarily political problem: the construction of a new society along collective, communist principles”. Figurative art was the art of the bourgeoisie; abstraction was the art of the people, and art could be dissolved into propaganda (manifestos, leaflets distributed on the subway system). They condemned the populist president, Pern, as “fascist”, and looked to destabilise art conventions, often with humour and irreverence. Unfortunately for them, their artistic heroes were Malevich and Rodchenko, who represented an aesthetic long proscribed in a Soviet Union, which now approved only social realism. In consequence, those among the Argentinian tyros who were members of the Communist party were soon expelled, after which their compositions of geometric shapes, diagonal lines and colour planes became, in many ways, more beguiling, and they joined a more general and international postwar abstraction movement.

A new development in Buenos Aires was the rejection by Rhod Rothfuss and others of the conventional picture frame, and an adoption of a symmetrical-shaped canvases. In Carmelo Arden Quin’s Trio No 2 and Juan Mel’s Irregular Frame No 2, for instance, the idea is to allow the edge of the painting to play a more active role — an attempt to subvert even more thoroughly than other concrete art the illusion of providing a representational “window on the world”, an illusion in which the rectangular frame plays a vital part.

In the third story, the scene shifts to 1950s Brazil, a far more nourishing environment than Argentina for geometric painters. In the way that abstract expression summed up an American idea of “freedom”, the natural language of Brazilian art at this time was concretism, carrying with it a sense of planning and modernity. Oscar Niemeyer’s brutalist capital Brasilia was in development and, unlike in Argentina where Peronist politics had hollowed out the middle classes, in Brazil the bourgeoisie was thriving. The new galleries in Rio and Sao Paulo established a proper art ecosystem.

As with all the artists in the Radical Geometry show, Waldemar Cordeiro felt that painting should be entirely free of any basis in observed reality and have no symbolic implications. “We defend the real language of painting that is expressed with lines and colours that are lines and colours and do not want to be pears nor men,” he wrote. The Brazilian concretists went in for rigorous geometry and bold pigments in the pursuit of pure, two-dimensional visuality. Cordeiro is represented in the show by the striking Visible Idea, a pair of interlocking shell-shapes on a crimson canvas.

Then, in 1959, things changed again in Brazil with the arrival of the neo-concretists. The centre of gravity was now warm Rio rather than cooler Sao Paulo, and the abstract art became less austerely rational and more organic, more playful — more comfortable with ideas of subjectivity and nature. Oiticica’s grids from the late 1950s have a bit of give: the squares seem to jostle, wanting to be free.

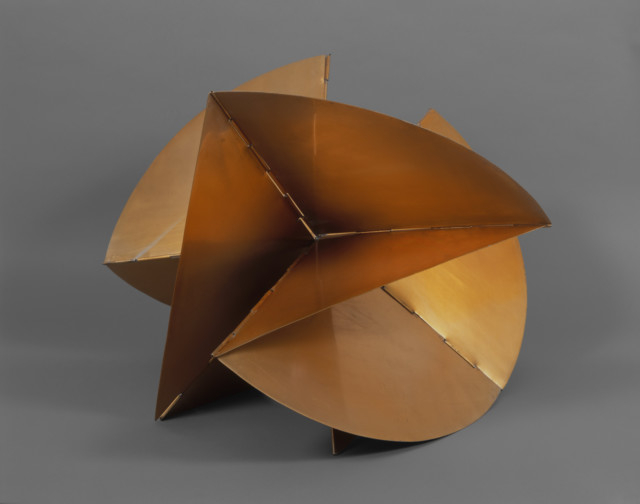

Lygia Clark’s Composition from 1953, with its egg-yolk yellow, navy and emerald rectangles, while gorgeously rendered, is a grid of planes from the same phase as her small, monochromatic paintings in grey, black and white. In her new mode, her structures drifted apart. Like Oiticica, she decided that ultra-rational abstraction was art for bourgeois insiders rather than the people, and it wasn’t participatory enough. (Both artists were inspired by the use of art therapy in a local psychiatric hospital.) Clark’s movable, aluminium origami-esque Bichos or Creatures are designed to make the spectator an active part of the artwork. As Adrian Searle put it last month when reviewing her retrospective, “as you play with them these small hinged forms flip-flop and fold this way and that. They have a nice weight, and handling them feels a bit like doing card tricks.” Oiticica’s capes for use in samba performances were another expression of participatory art. Similarly, Lygia Pape produced books with semi-abstract sculptural elements that viewers were encouraged to pick up and investigate.

Radical Geometry’s fourth Venezuelan story is characterised, like the first, by strong connections between Latin America and Europe. The op and kinetic artists Jess Rafael Soto and Carlos Cruz-Diez crossed the Atlantic and settled in Paris. In the other direction, Gego, who was born Gertrud Goldschmidt, the daughter of a Jewish banker, left Germany in 1939 as political tension mounted, bound for Caracas. She arrived during an economic boom, and was surrounded by artists consumed by a sense of new possibility.

Encouraged by Alejandro Otero and Soto, who were experimenting with light and perception, Gego created three-dimensional works, first with paper and then with iron and steel. She titled her beautiful, fragile, hanging wire structures — a new form of abstract, line-based art — Drawings Without Paper, refusing to call them sculptures. Radical Geometry has half a dozen of her works including Square Reticularea 71/6, which takes the idea of the geometric grid so prevalent throughout the exhibition and makes it floating, weightless, almost invisible; Decagonal Trunk No 4, which stretches the grid down into a long Chinese lantern-shape; Sphere, an intricate round steel net; and Flow No 7, which is all draped lines, like a crestfallen chandelier. They mark a long distance travelled from the original concrete art that influenced Torres Garca, and are among the visual revelations that pack this fascinating show.

–Guardian News & Media Ltd

Radical Geometry: Modern Art of South America from the Patricia Phelps de Cisneros Collection is at the Royal Academy, London through September 28.