The venue is the Asia Society in New York which is about to witness a “very unique” production of the Odissi dance, as Rachel Cooper, Asia Society’s director of performing arts, would later in the evening tell the audience in the auditorium while introducing to them an acclaimed Malaysian performer and interpreter of the 2000-year-old Odissi genre of classical Indian dance.

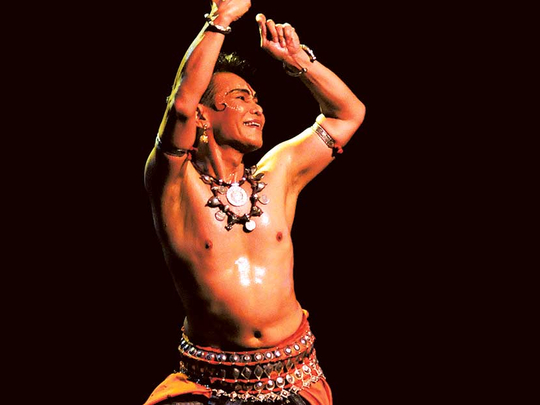

The Malaysian performing dancer in question is Ramli Ibrahim who recently enthralled audiences for two days at the Asia Society and presented a visually and artistically perfect production depicting a chapter about the Hindu deity Krishna.

I have, meanwhile, arrived an hour early at the Asia Society to interview Ramli before he goes on the stage to perform with his troupe of dancers. Malays, as a custom, do not use a surname, and are generally addressed by their first name. I am ushered backstage by a female employee of the organisation where I meet Ramli attired in his colourful Indian dance costumes, painted face et al, as he prepares for his dance production called Krishna: Love Re-invented.

“I actually studied mechanical engineering at the University of Western Australia in Perth from 1970 to 1975, and obtained a degree in this subject. But since a very young age, I was fascinated by classical ballet. So, I began to study it in Western Australia while completing my studies in mechanical engineering. At that point, ballet dancing was still very much a hobby for me, but it developed, later, into a full-time passion that drove me to join the Australia Ballet School in Melbourne,” Ramli reminisced in his interview with Weekend Review.

“I was also fortunate to be invited by Graeme Murphy, one of the icons of contemporary dance, to perform. At the same time, I was exploring my Asian roots. I was also looking outside of Malaysia and turned to India as the mother country of multiple cultures and religious diversity. Even as I toured the world with the Sydney Dance Company, I worked on my own as a classical Indian dancer (Odissi and Bharatnatyam). I was exposed to the techniques of Odissi dancing of Devaprasad, and Bharatnatyam of Adyar Laxman. However, I developed my own strengths and began to perform solo. But, as you know, it is not an easy thing being a male dancer. Male dancers can hardly afford to make a livelihood out of dancing. Sons are, consequently, not encouraged by their parents to follow such a career path,” Ramli observed.

To pursue Odissi as a full-time profession, Ramli said, one had to be committed “heart and soul” to it besides, of course, having the passion for it. “I had both these qualities,” he added. The youthful-looking dancer’s “elastic body”, as one American told me, makes him look as if he is in his early or mid-forties instead of his ripe 62 years.

Recalling the long period of dedication and full commitment to the dance, Ramli muses: “I think one’s métier in dance or the arts is an on-going journey of discovery. It’s not a completed journey where one counts the years and can claim that one has achieved perfection. I have never reflected on the level I may be at or have reached in my art. It keeps growing and going at different directions and levels.”

Ramli has set a record by performing in more than 100 cities worldwide.

He describes his performance each time as an “offering”. “I try to focus on giving the best of myself to the best spirit residing within me. I try not to play to the gallery and entertain the audience,” he observed.

But he has had his share of problems too, as he began his painstaking journey towards perfecting his Odissi dance techniques. One major problem that stares at any one venturing into this field is earning a decent income. Odissi dancing does not pay much. Besides zeal and passion, one needs the stomach to endure the rigours of the tough and hardly rewarding profession that is quite a contrast to the opportunities available to an incumbent with a degree in mechanical engineering.

“I had the sustainability and the willpower to endure this because deep down I knew I was destined to become an Odissi performer. Dance, after all, chose me rather than I choosing dance!” he muses and then gently smiles, adding that it is a “struggle and you are never going to make it, unless you love dancing”. “You need sheer love of dancing to keep you going, only then you can achieve your goal,” he said.

India has become a second home for the Malaysian which he visits some eight or nine times a year. Indeed, he has created a fan following in India where he is recognized as one of the leading exponents of Odissi dancing.

The Malaysian dancer, choreographer and teacher, received a national award, the Sangeet Natak Academy Award, from Indian President Pranab Mukherjee in 2011 for his outstanding contribution to the cause of peace through his dancing.

“India has helped us a lot,” he says.

Asked how he felt as a Malaysian performing a classical Indian dance depicting Krishna’s teasing and playfulness with Radha and the “gopis” (cowherd girls), Ramli responds by saying that the audiences never, for a moment, questioned his origin. “Here, for example, in New York, the avant-garde and traditional interact to stimulate one another. The atmosphere of freedom in expressing oneself has been palpable from the start: the question of being a Malaysian performing an Indian dance in the US or India has never been an issue. New York is the centre of dance, and both the avant-garde and the traditional artists have sought to find affirmation of their art in this great city. I have performed with my group in Carnegie Hall in 2008, in Washington DC in 2008 and at the Downtown Festival at Battery Point in 2010,” he says.

Ramli’s dance troupe has performed many times in the US. “I first performed in New York in 1981 with the Sydney Dance Company where I was discovered by the great dancer, the late Indrani Rehman. She organised many performances for me in New York in the 1990s,” he says.

The performance at the Asia Society attracted not only mainstream Americans, but also American-Asians who included Indians and a mix of Nepalese, Bangladeshis, Indonesians, Malaysians, Pakistanis, Singaporeans, Chinese and Japanese.

For his latest production “Krishna: Love Re-Invented” which was presented during his tour of the US and Canada, Ramli meticulously studied the nuances of the Krishna saga, which he interpreted and conveyed through subtle dance movements and, more importantly, through his eyes. The production was organised under the aegis of the Sutra Dance Theatre, which is part of an institution called Sutra Foundation of which he is the chairman. The Sutra Foundation conducts various activities ranging from giving performances (Sutra Dance Theatre), through teaching (Sutra Academy) to organising exhibitions (Sutra Gallery).

The production “Krishna: Love Re-Invented” explores the “madhurya” essence of love in its “sweetest and honey-like appeal” related to the Hindu deity Krishna whose playfulness with his circle of “gopis” — one could possibly describe it, in today’s parlance, as an elegant form of flirting — has been the subject of a multitude of writings, poems, songs and even films. What is depicted in this particular production is not Krishna, the hero and counsellor of the Mahabharata, or Krishna, the prince who killed the demon Kamsa, but Krishna, the pastoral deity and cowherd, the lover of the gopis.

Framing the Hindu deity Krishna as the ultimate embodiment of love and focusing on Radha’s all-consuming love for him, Ramli describes this piece as a “dance that is a celebration and liberation of the body, mind and soul”.

While Ramli clearly is the creative leader and the driving force of the troupe, one cannot ignore the impressive performance of the other dancers who are part of the production. There is Geethika Sree who excels in both Bharatnatyam and Odissi whose “angasuddha” (perfection of body pose) is remarkable. Sivagama Valli, proficient in ballet, Bharatanatyam and Odissi, has already toured a number of countries with the Sutra Dance Theatre while Divya Nair, who is of Indian and Chinese parentage, is a gifted dancer who has also been on overseas tours with the Sutra. Tan Mei Mei, equally proficient in ballet, Bharatanatyam and Odissi, is a dynamic dancer in full control of her technique. Thrisherna, a prodigy, was trained in Odissi and Bharatanatyam by the time she was 17; she displays a remarkable aptitude for movement and has participated in many of Sutra’s tours. Gauthami, Sutra’s next fresh talent, is endowed with natural grace and facility of movement. Jagatheyswara, who started dancing at 13 with Sutra, holds dance as a spiritually binding “sadhana” which is evident in his abhinaya renditions. Jagatheyswara, who pursued post-graduate studies in information management, currently works with an IT firm.

Has the Sutra troupe performed in any Islamic country? “As a matter of fact, we have performed in Oman and Indonesia. Indonesians are more open than Malaysians in appreciating this type of classical dancing. There is a strong Hindu culture influence in both Indonesia and Malaysia, though I have also encountered some hostility in Malaysia. The Indian community in Malaysia — I don’t consider them to be the Indian diaspora but as people who have been living in Malaysia for generations — has been very supportive as also other communities. Someday, I would like to do a performance in Pakistan,” Ramli says.

Given the growing number of classical dancers performing in films, particularly Bollywood, would he not be interested in doing roles in movies? “Oh, yes, I would collaborate with a good, sensitive film director who must have aesthetic sensitivity. I have already worked with many upcoming Malaysian film directors. I have always felt films are an important vehicle for communicating with the audiences.”

At the conclusion of the performance at the Asia Society, the audience was so enthralled that they gave Ramli and the members of the Sutra Dance Theatre a standing ovation.

Manik Mehta is a commentator on Asian affairs