Between Two Worlds: How the English Became Americans

By Malcolm Gaskill, Basic Books, $54.60

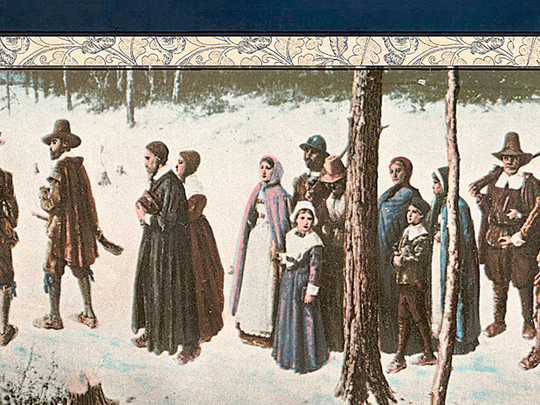

The 17th-century prologue to American history holds a deep significance well beyond offstage scene-setting. Thanksgiving — a commemoration of the pilgrim fathers’ first harvest in 1621 — remains a binding quasi-religious ritual in a nation that lacks a formal state church.

Moreover, the claim that the original thanksgiving meal was attended by both pilgrims and Native Americans provides modern multiracial America with a convenient founding legend of friendly cross-cultural encounter. A similarly selective reading of events at the Jamestown colony in early 17th-century Virginia reinforces this message.

Here the welcoming Pocahontas , daughter of a Native American chief, assisted the colonists and went on to marry a tobacco planter named John Rolfe. The early colonial era also features prominently in the political realm. Presidents and aspiring presidents routinely invoke the rhetorical trope of America as “a city upon a hill”, first deployed by John Winthrop, the leader of the Puritan migration to Massachusetts in the 1630s.

But this is England’s past as much as America’s, notwithstanding the tendency of Americans to treat English history as “backstory” to the making of their nation. Malcolm Gaskill’s absorbing account of 17th-century English colonisation in various parts of North America works against the grain of preconception to restore “a neglected dimension of the history of England”.

The myth of daring innovators who set out “to build a new world” cannot withstand careful scrutiny of the restless homeland left behind. As often as not, Gaskill notes, colonists had a defensive mission — “to recreate a world felt to be vanishing at home”. Nostalgia — contrary to received assumption — predominated in this brave New World. Landowners wanted to revive old-style feudal estates, farmers aspired to “small holdings”, Puritans wanted to restore the uncorrupted practices of “the early church”, and everybody wished to recover the “good fellowship” and communal warmth of Old England.

Merry England, however, was more controversial. The pilgrim fathers’ colony at Plymouth was riven over the erection in 1628 of an 27-metre maypole, which offended killjoys as a species of heathen idolatry. As Gaskill is keen to remind us, the antagonisms of the old world did not vanish in America, but were rekindled in new settings, with the failure to realise nostalgic dreams intensifying disappointment and unpleasantness.

However, higher-level social frictions of this sort only flared up when society itself had passed the threshold of bare survival; and this was sometimes a long time coming. We are all too accustomed to viewing North American colonisation in retrospect as a glorious success story for all but the native Americans and their environment.

In Gaskill’s account, we are reminded that it was a close run thing, for the native Americans and a hostile environment — ice storms, humidity, diseases — almost saw off the colonists. The population of Roanoke colony on an island on the outer banks of what is now North Carolina vanished without trace in 1590, their quarters ransacked.

The frozen colonists at Sagadahoc in Maine were more fortunate to be repatriated in 1608. Indeed, from the start, there was plenty of “reverse migration”, back to the motherland. Although New England and Virginia provide the focal points of Gaskill’s study, he does not neglect a wider culture of English colonisation in the north Atlantic — from nearby Ulster, the primal scene of colonial dispossession, to Newfoundland, Bermuda and Barbados.

Each setting brought its own distinctive hazards, sometimes environmental, but arising too from the prickly differences of the settler population. The religious and political divisions which took the motherland to civil war in the 1640s were not only replicated across the colonial world, but — untrammelled by tradition or conventions of church discipline — assumed poisonously exaggerated forms.

During the 1640s, many New England Puritans returned to the motherland to fight for the parliamentary cause, especially university-educated men. Appalled as they were at the carnage, destruction and division they witnessed in England, several of these were glad — as Gaskill discovers — simply to be back. For them the hypersensitive factionalism and dogmatic will-to-tyrannise of unconstrained frontier Puritanism had proved more draining than an Old World civil war.

While the execution of Charles I and the triumph of the republic in 1649 attracted reverse Puritan migration to England, it prompted royalists to seek refuge in loyalist Virginia. Ideological battle lines in the 17th century did not run between England and America, Gaskill reminds us, but within both England and America. In 1651 the republic used force to bring about regime change in Barbados, whose uneasy neutrality during the civil wars had given way after the execution of Charles I to an overt royalism.

At the Restoration of Charles II in 1660, Massachusetts loomed large to the Cavalier elite as a semi-republican haven for regicides and other troublemakers.

The 1670s brought a further wave of conflict to the colonies: in New England the revolt in 1675 of Metacom, chief of the Wampanoag — better known by his nickname, King Philip — and Bacon’s Rebellion of 1676 in Virginia, where the colonial establishment was threatened by what seemed like a white rabble, including former indentured servants, more desperate than their social superiors to seize land from native Americans.

The planters learnt a long-term lesson. Imported black slave labour from Africa was potentially less troublesome than an assertive white servant class. Carolina, meanwhile, was settled under the auspices of a neo-feudal form of government modelled on the medieval palatinate of Durham. Church, king and a hierarchical social order provided the general template for the south, but the northern colonies still served as an irritant reminder of mid-century rebellion and ongoing post-Restoration truculence.

The undisguised Roundhead sympathies of Puritan Massachusetts and some of its neighbours provoked the Stuarts into revoking their charters and — significantly — abolishing their representative assemblies. Instead, Massachusetts, Maine, Plymouth, New Hampshire and parts of Rhode Island were remodelled in 1686 as the authoritarian Dominion of New England.

Its first governor, Sir Edmund Andros, had proved his loyalty in the suppression of Monmouth’s rebellion in the English west country in 1685, after which many of the rebels had been transported to the West Indies. The British Atlantic had become integral to the policies of Stuart despotism.

However, this intrusive new government only lasted a few years. When news of England’s Glorious Revolution reached New England in the spring of 1689, a popular uprising ensued in Boston and Andros was overthrown. The traditional forms of colonial government — though barely half a century old — were reinstated. The revolution of 1689 in New England now seems like an augury of future assertiveness. Yet each popular uprising in the colonies invoked the traditional “liberties of Englishmen”. At the close of the 17th century the real underlying tensions, as Gaskill perceives, were between creole identities — where the demands of each particular colonial environment thwarted aspirations to be English — and processes of reanglicisation.

As the various colonies integrated with the British economy from the early 18th century, and developed consumer cultures, so each colony became less singular and more deferential towards standards set in London. Instead of a patchwork, colony by colony, of distinctive creole futures, what seemed to lie ahead was a shared provincial identity in thrall to metropolitan fashion. American independence was not yet a gleam in the eye.

–Guardian News & Media Ltd