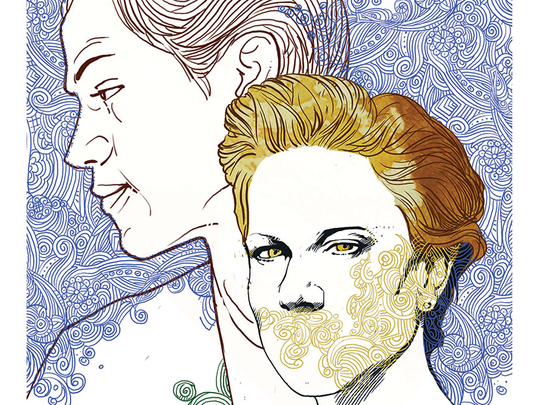

A Spool of Blue Thread

By Anne Tyler, Knopf, 368 pages, $25.95

Breathing Lessons was the name of Anne Tyler’s 11th novel — but she has never needed to be taught how to give her characters life. The extraordinary thing about all her writing is the extent to which she makes one believe every word, deed and breath.

“A Spool of Blue Thread”, her 20th, is no exception. What is most remarkable about it is the extent to which Tyler is able to relax into an ordinary, homely minor key while keeping one as absorbed as if it were one’s own family she were describing, and as if what happened to them were necessary reading. The book is no less eventful than ordinary life — and that turns out to be more than enough.

The novel is a portrait of the Whitshank family across several generations. Denny, 19 when the story starts, something of a prodigal son, is reminiscent in his charming, maddening, potentially delinquent way — balanced bewilderingly yet convincingly between helpfulness and fecklessness — of Jack, the returning bad lot in Marilynne Robinson’s Home. Tyler is in the top rank of American writers, and moments in this novel have an affinity with Canada’s

Alice Munro too. But what she has that neither Robinson nor Munro possess to the same degree is an irrepressible sense of the comedy beneath even the most melancholy surface — or sometimes peeking just above it — in human affairs.

Tyler is good on irony too. The son who has most tormented his mother most colonises her heart. Not that Denny registers Abby’s favouritism, having spent a life feeling jealous of his adopted younger brother Stem. Abby, a social worker, married to Red, who works in construction, is the heart of the family and the novel.

In her seventies, she is starting to unravel in small but alarming ways while staying defiantly her own person. As a social worker Abby used habitually to find a place for lame ducks at her table and still does, given half a chance. But now she is becoming a lame duck herself — and Denny has shown up to support her. The trouble is that Stem and his beautiful Baptist wife, Nora, have got there first.

Abby gets infuriated by Nora’s presence and manner, asking herself why Nora persists in calling her “Mother Whitshank”: “It made Abby sound like an old peasant woman in wooden clogs and a headscarf.”

Tyler is sensitive to the tragicomedy of old age and its indignities. Her writing is characterised by an amused, sweeping tolerance that acknowledges imperfection at all ages. Flakiness, mystery and unpredictability worm their way into the narrative as Tyler resists the temptation to know everything about her own characters: many stay mystifying — as real people do. And when, one day, Abby sets out with the dog, Brenda, confidently calling it Clarence (the name of a deceased family pet), it is in no way guessable what the consequences of an apparently inconsequential walk will be.

Tyler writes with witty economy. She finds many inspired short cuts. Denny has a brief, doomed marriage to a woman named Carla who is described as looking “pleasant but distracted, as if she were wondering whether she’d left a burner on at home”. It is descriptions of this kind — entertainingly spot-on — that are such a joy. Denny is described as having the good looks that people remark upon “in a tone of surprise as if they were congratulating themselves on their powers of discernment”. It is an enjoyable dig at the irritating way people state the obvious as if it were revelatory.

The family house on Bouton Road is a character itself — its veranda sheltering the story. It is introduced as having the “comfortably shabby air of a place whose inhabitants had long stopped seeing it”. And it is through the house that Tyler plays a trick with time in a bittersweet shift back into Abby’s youth and the house’s early days.

We meet Abby’s upwardly mobile father-in-law, Junior, and Linnie, his devoted, apparently pitiable — but actually triumphantly tenacious — wife.

The description of their marriage is one of the novel’s highlights, coming to a head in a subtle, agonising disagreement about the colour a swing is to be painted. Junior is a fanatic about taste. His wife wants the swing painted “Swedish blue”, a homage to a swing of her youth. Junior tells her the colour is lower-class. Who would have guessed that so much would hang on such a trifling matter? It takes organised wit to write about human muddle as Tyler does, without once losing our attention or the narrative’s spool of blue thread.

Guardian News & Media Ltd