In a 2002 obituary in the London Independent, the prolific Arab writer Adel Darwish reported that when Colonel Muammar Gaddafi visited the University of Libya in Benghazi in April 1973, a group of students confronted the future King of Africa over freedom of thought and an individual's right to choose.

The colonel was not amused, since he was habituated to hearing hysterical chants that lauded his "cultural revolution" and ordered an investigation. To his chagrin, he discovered that the protesters were philosophy students, all trained by an Egyptian professor, Abdul Rahman Badawi. It was not long before the poet/philosopher was arrested and deported out of the Jamahiriyyah.

Early life and education

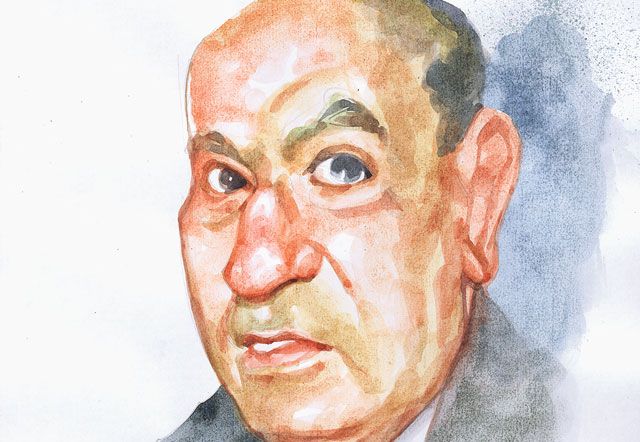

Like most genuine thinkers, Badawi became a thorn to ruling elites, who preferred to seek gratuitous adulation. One of the most eminent 20th century Egyptian philosophical figures and scholars, Badawi was born in Sharabas, Damietta governorate, and quickly distinguished himself at the European-style public school, Saydiyyah. He graduated first in his class (1938) and was offered a fellowship by the King Fuad University — where studies were conducted in French, English or Latin.

At three universities — the Egyptian, Fuad (now Cairo University) and Ibrahim (now Ain Shams University) — he earned academic accolades from his professors and colleagues. André Lalande and Alexandre Kouré, two faculty members with impeccable reputations for scholarship, supervised his original work, Le Problème de la Mort dans la Philosophie Existentielle [The Problem of Death in Existentialism], which was published in 1964 and which inspired generations of Egyptian thinkers.

As a prodigy, Badawi lectured students on research methodology and metaphysics, and after 1939, taught the history of Greek philosophy, interpreting French texts to students. With a doctorate (1944), Badawi accepted an appointment as lecturer in the Department of Philosophy, Fuad University, and was seconded as professor of Islamic philosophy to the Higher College of Arts at the Université Saint Joseph in Beirut, Lebanon (1947-1949). He then returned to Cairo and moved to the Ibrahim Pasha University (1950), where he founded and headed a brand new Department of Philosophy, a position he kept until 1971.

These teaching responsibilities were supplemented with political appointments, first as a cultural counsellor and head of the Egyptian educational mission in Bern, Switzerland (1956-1958), and after the 1952 Egyptian Revolution brought to power Jamal Abdul Nasser, a stint on the Rais's Constitutional Committee. Badawi pursued his academic life overseas, first in Benghazi, Libya, between 1967 and 1973, then at the Faculty of Theology and Islamic Sciences at Tehran University (1973-1974) and then at the University of Kuwait University from 1974 to 1982, when he retired from teaching.

Political life

Inasmuch as contemporary philosophy confronted aspiring dictators in the post-Second World War Middle East, Abdul Rahman Badawi was inevitably drawn to national politics, and became actively involved in various parties. As early as 1938, he joined the Misr Al Fatah Party before switching to the Neo-National Party in 1944, when he was appointed to the latter’s Higher Committee. In January 1953, Badawi was one of the 50 Egyptians chosen by Jamal Abdul Nasser to serve in an allegedly independent Constitution Committee, whose writ was to draft a new constitution for the country.

Naturally, Egypt did not lack competent politicians, intellectuals and jurists, and while Nasser surrounded himself with talent, he was wary of their contributions, which introduced provisions that promoted freedom and duty. Badawi, along with dozens of eminently qualified members, insisted on a liberal democratic position, which did not please the Rais.

The committee’s final draft was duly rejected by the new regime and, after 1954, entirely abandoned, only to be replaced by a watered-down 1956 version. At a later stage in his life, Badawi insisted that Nasser had "aborted Egypt’s liberal experiment, which could well have developed into a full democracy". Dejected by the regime, he was "encouraged" to leave the country in 1966, and he returned only near the end of his life.

The exile — compulsory and the self-imposed — lasted 34 years although European colleagues who were well acquainted with his work regarded him as a "safe haven of light and enlightenment". His treatment in Benghazi, which earned him 17 days in the Libyan Colonel's jails, reinforced his political determination. Both his Cairo and Benghazi experiences persuaded him that free thinkers were no longer welcome in the Arab world. He lamented the 1952 Nasser military coup that subsequently became a model for other revolutionaries and it was only through the personal intervention of president Anwar Sadat, who was familiar with a few of his writings, that Badawi was released and expelled. Towards the end of his life, president Hosni Mubarak recognised Badawi’s unique contributions and awarded him Egypt’s highest prize for letters — a gesture that spoke more of the Egyptian leader than the recipient.

His philosophy

The erudite student tackled difficult subjects and immersed himself in philological methodology, focusing on Greek heritage and how the latter influenced the Muslim world. Still, he was first and foremost a student of German philosophy, especially Heideggerian. A rare academic phenomenon, since he could read and write with equal ease in English, Spanish, French, German and Arabic (with working knowledge of Greek, Latin and Persian), Badawi reasoned that the nature of Islamic civilisation could only be defined by measuring its reaction to its Greek counterpoint.

He argued that if a civilisation denied individual identity before a higher deity, it would be nearly impossible to produce philosophy to comprehend the spirit of the latter. As reported by Darwish, Badawi identified the 11th century fatwa by Ibn Salah Eddin Al Shahrouzi, “banning studying logic as ‘heresy delivering man into Satan’s bosom’ — still upheld by fundamentalists” — as an example of the contradictions between the basic philosophies of the two. This, Badawi posited, is “the key to understanding the continuous conflicts between Islam and the West”, which also predicted tragedies such as September 11, 2001, that highlighted the unavoidable “clash of civilisations”.

Though Badawi was a student of Heidegger, his version of existentialism differed from the German’s — and perhaps other existentialists’ visions too — in the sense that he gave priority to action rather than thought. Moreover, he recognised that a thinker ought to find the meanings of existence in reason, emotion and will all together and in the living experience that depends on inner feelings, which are capable of comprehending existence. These thoughts evolved as the works of Jean Paul Sartre and Heidegger were at the height of their popularity, with Badawi rivalling his European counterparts as the torch-bearer of existentialism in the Arab world.

Because Badawi translated so many great works, several critics assumed he was a mere disciple of his European counterparts, which is a huge error. Badawi displayed originality in trying to root his ideas in his own culture, notably in Humanism and Existentialism in Arab Thought (1947), which added considerable value to the debate. It was his near-native fluency in several European languages that allowed him to fully understand European existentialism and identify points with which he differed.

The author of over 120 books, Badawi believed that Islam and Christianity were complementary and compatible, linked in a common and perpetual chain. Needless to say that such a thesis is contrary to contemporary extremists on both sides, although Badawi posited that Christians knew and appreciated the role of Islam in Greek philosophy and heritage. His seminal works from Aristotle onwards identified Christianity’s cultural debt to Arabs and Muslims. Even if some of his early books were critical of Islam, including his Dissidents in Islam (1946) and the highly controversial A History of Atheism in Islam, he defended the Quran and the Prophet Mohammad (PBUH) in his decisive books Défense du Coran Contre ses Critiques (A Defence of the Quran Against its Critics, 1988) and Défense de la vie du Prophète Mohammad contre ses Détracteurs (A Defence of the Life of the Prophet Mohammad against his Detractors, 1990).

Legacy

Generations of Arab thinkers who enlightened the rest of the Middle East were inspired by Badawi (1917-2002), who will remain one of the most prominent Arab philosophers of the 20th century. The English reader will appreciate an Arab intellectual who rejected totalitarianism and spoke against it as an irrational thought, based on sentimental ideology, and called on Arabs to emphasise individual freedoms that allow each person to make informed choices. Much like Nietzsche, who spoke of the “superior man”, Badawi avoided distractions from his “greater missions in life”, which include fighting ignorance and wrangle against hypocrisy.

Multifaceted talent

Abdul Rahman Badawi was born on February 4, 1917, in Sharabas, a village in the Damietta governorate, to a relatively wealthy rural family. A solid student, the young graduate joined the Faculty of Arts of the Egyptian University, which eventually became Cairo University. Badawi was a controversial figure but a highly-praised pioneer.

On October 15, 1938, Badawi was appointed lecturer at the Department of Philosophy, to assist renowned Professor André Lalande on research methodology and metaphysics. Starting in January 1939, he taught the history of Greek philosophy, interpreting original texts to students and, by November 1941, was advanced enough to earn a masters with professors Lalande and Alexandre Kouré.

His thesis, The Death Problem in Existentialism (1964), was written in French, and published by the French Institute for Oriental Archeology in Cairo. On May 29, 1944, Badawi obtained his doctorate in philosophy at Fuad University (which was also merged into Cairo University) with a thesis titled Existentialist Time. A distinguished academic career followed with appointments at Fouad University, the Ibrahim Pasha University and the Université Saint Joseph in Beirut, Lebanon.

Letters and leadership

Over the years, Badawi also worked as a cultural attaché and head of the Egyptian educational mission in Bern, Switzerland (1956-1958), and taught at the Sorbonne in Paris (1967), the University of Libya in Benghazi (1967-1973) and the University of Tehran (1973-1874).

In 1974, he moved to Kuwait University, where he worked until his retirement in 1982. In addition to his academic life, Badawi was an active participant in national politics, first as a member of the Misr Al Fatah Party (1938-1940), then a member in the Higher Committee of the Neo-National Party (1944-1952). In 1953, he was appointed to the Constitution Committee by the revolutionary government, which commissioned it to draft a new constitution for Egypt.

Of the 50 members that served on the committee, Badawi stood out as a real intellectual, insisting on various clauses that ensured freedom of speech and assembly that, sadly, were routinely ignored. One of the few Egyptians who spoke to Jamal Abdul Nasser, Badawi claimed that the Rais “aborted Egypt’s liberal experiment, which could well have developed into full democracy”.

Disenchanted with lofty promises, he left the country in 1966, only returning at the end of his life when president Hosni Mubarak mustered the political will to award him Egypt’s highest literary prize in 1998. Although Badawi was romantically involved with several European women, these were short-lived and he never married. He died in Cairo on July 25, 2002.

Key publications

Badawi was a prolific writer, with more than 120 books on philosophy and literature, of which several tomes stood out. His first book on Nietzsche was published in Cairo in September 1939. Although the vast corpus was written in Arabic, five volumes were composed in French, a language he mastered with aplomb. In addition to many books, Badawi published hundreds of articles and research papers, participated in international conferences throughout the Arab world and made presentations in French, English, German and Spanish.

A short list of his philosophical works:

- Nietzsche, Cairo, 1939

- Greek Heritage in the Islamic Civilization, Cairo, 1940

- Plato, Cairo, 1943

- Aristotle, Cairo, 1943

- The Spring of Greek Thought, Cairo 1943

- The Autumn of Greek Thought, Cairo 1943

- Existentialist Time, Cairo 1945

- Humanism and Existentialism in Arabic Thought, Cairo, 1947

- The Spirit of Arab Civilization, translation and study, Beirut, 1949

- Aristotle’s Logic, Cairo, Part I (1948), Part II (1949) and Part III (1952)

- Art of Poetry by Aristotle, translation and study, Cairo, 1953

- Greek Origins of Political Theories in Islam, Cairo, 1955.

- Synopsis of Oratory by Ibn Rushd’s verification and study, Cairo 1960

- Studies in Existentialism, Cairo, 1961

- Scientific Research Methodology, Cairo, 1963

- Ibn Khaldun’s Works, Cairo, 1963

- The Arab Role in Forming European Thought, Beirut, 1965

- A New Introduction to Philosophy, Kuwait, 1975

- Ethics in Kant’s Opinion, Kuwait, 1977

- Al Ghazali’s Works, Cairo, 1981

Dr Joseph A. Kéchichian is an author, most recently of Faysal: Saudi Arabia’s King for All Seasons, Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida, 2008.

Published on the second Friday of each month, this article is part of a series on Arab leaders who greatly influenced political affairs in the Middle East.