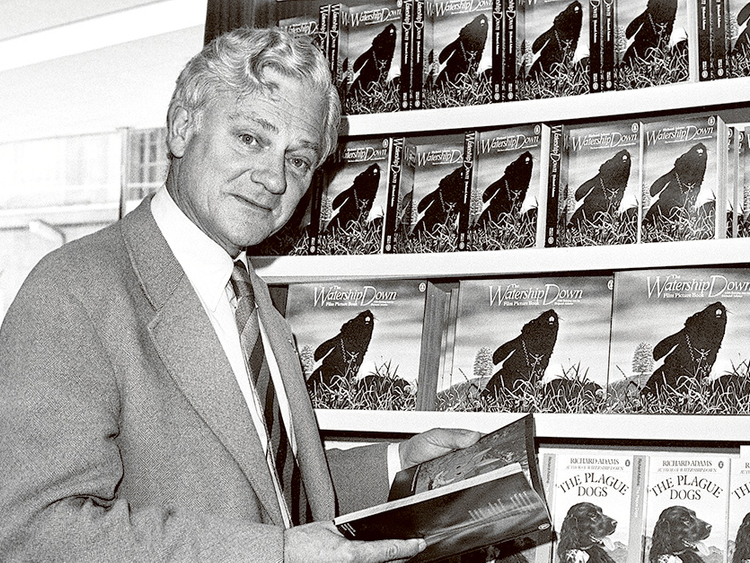

London: Richard Adams, the British novelist who became one of the world’s all-time bestselling authors with his first book, Watership Down, a tale of rabbits whose adventures in a pastoral realm of epic perils explored Homeric themes of exile, courage and survival, died on Saturday. He was 96.

His daughter confirmed his death, the BBC and other British news organisations reported. No other details were given.

For much of his life, Adams was an anonymous civil servant in London who wrote government reports on the environment. But he was also an unpublished dabbler in fiction, an amateur naturalist and a father who made up rabbit stories to entertain his two young daughters on long drives in the country.

When he was 50, at their urging, he began turning his stories into a book intended for juveniles and young adults, writing after work and in the evenings. It took two years. Set in the Berkshire Downs, where he had grown up, a quiet landscape of grassy hills, farm fields, streams and woodlands west of London, Watership Down was a classic yarn of discovery and struggle.

Facing destruction of their underground warren by a housing development, a small party of yearling bucks, led by a venturesome rabbit named Hazel, flees in search of a new home. They encounter human beings with machines and poisons, snarling dogs and a large colony of rabbits who have surrendered their freedoms for security under a tyrannical oversized rabbit, General Woundwort.

The pioneers realise that founding a new warren is meaningless without mates and offspring. With a sea gull and a mouse for allies, they raid Woundwort’s stronghold, spirit away some of his captives and confront his forces in a pitched battle in defence of their new warren on Watership Down.

It is a timeless allegory of freedom, ethics and human nature. Beyond powers of speech and intellect, Adams imbued his rabbits with trembling fears, clownish wit, daring, a folklore of proverbs and poetry, and a language called “Lapine”, complete with a glossary: “silflay” (going up to feed), “hraka” (droppings), “tharn” (frozen by fear), and “elil” (enemies).

Despite its originality, the book had an unpromising start, rejected by literary agents and publishers. But in 1972, a small house, Rex Collings Ltd., printed a first edition of 2,500 copies. British critics raved, comparing the book to George Orwell’s Animal Farm and to the fantasies of J.R.R. Tolkien, Jonathan Swift and A.A. Milne. A year later, Penguin issued the novel in its Puffin Books children’s series.

Adams readily acknowledged criticisms that Watership Down borrowed much rabbit lore from R.M. Lockley’s nonfiction study, The Private Life of the Rabbit (1964). But the authenticity of Adams’ book as an anthropomorphic fantasy with classic motifs was not challenged, and in Britain it won the Carnegie Medal in Literature in 1972 and the Guardian Children’s Fiction Prize in 1973.

In 1974, Macmillan published the first US edition. American reviews were mixed. Peter Prescott gave it a glowing review in Newsweek, and Alison Lurie, in The New York Review of Books, called it “a relief to read of characters who have honour and dignity, who will risk their lives for others.”

But Richard Gilman, in The New York Times Book Review, said it fell far short of Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland and Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows, and predicted it would “find its true audience mainly among the people who have made a cult of Tolkien, among ecology-minded romantics and all those in need of a positive statement, not too subtle but not too blatant either, about the future of courage, native simplicity, the life-force, and so on.”

Watership Down quickly topped the New York Times bestseller list and remained on it for eight months. It was a Book of the Month Club selection. Avon paid $800,000 (Dh2.9 million) for the paperback rights. It eventually became Penguin’s all-time bestseller, a staple of high school English classes and one of the bestsellers of the century, with an estimated 50 million copies in print in 18 languages worldwide.

Adams quit the civil service in 1974 to become a full-time writer. He published a score of books: novels, short stories, poetry, nonfiction and an autobiography. Some sold well, but none approached the success of Watership Down, which was adapted for a 1978 animated film (with a song, Bright Eyes, sung by Art Garfunkel), an animated television series broadcast in Britain and Canada from 1999 to 2001, and a theatrical production in London in 2006.

Adams was a stout, ruddy-faced man with a big chin and a flying shock of silver hair that complemented his Harris tweeds and country life. He wrote longhand with a pen or pencil, producing 1,000 words a day. Before each session, he read aloud from Milton’s Paradise Lost, Spenser’s The Faerie Queene or C.K. Scott Moncrieff’s translation of Proust.

He told The Times of London in 1974 that he disliked modern novels “dominated by the problems of their heroes or heroines, who are constantly questioning their values.”

“As an Orthodox Christian,” he added, “I feel there really isn’t a lot of agonising to be done. I couldn’t write a story about right and wrong.”

Richard George Adams was born on May 9, 1920, in Newbury, England, one of three children of Evelyn George Beadon Adams, a doctor, and the former Lilian Rosa Button. He attended boarding school and a prep school, Bradford College, and in 1938 enrolled at Oxford University. His studies were interrupted by the Second World War service with British airborne forces in the Middle East and India.

He returned to Oxford and earned a degree in history in 1948. He then joined the Ministry of Housing and Local Government and worked his way up over 20 years to a senior post in the clean-air section of the environmental department. He also began writing short fiction in his spare time.

In 1949, he married Barbara Elizabeth Acland. They had two daughters, Juliet and Rosamond. There was no immediate word on his survivors.

In a 1975 interview with The Miami Herald, Adams recalled the genesis of his first book, as a story he concocted for his daughters.

“It was while we were driving to Stratford once, and they were begging for stories, that ‘Watership Down’ began,” he said. “All the principal ingredients were extemporised off the top of my head. It was about a fortnight before I finished telling it to them the first time.”

Adams became a fellow of the Royal Society of Literature in 1975, a writer in residence at the University of Florida in 1975 and at Hollins University in Virginia in 1976, and president of the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals in 1982.

In his second novel, Shardik (1974), the title character was a massive bear, alternately worshipped as a divine avatar and brutalised by barbarians in an ancient mythical empire. Reviews were mostly negative.

Other books included The Plague Dogs (1977), about two canine fugitives from an experimental lab; Traveller (1988), a Civil War chronicle from the viewpoint of Gen. Robert E. Lee’s horse; and Tales from Watership Down (1996), a sequel collection of stories. His autobiography, The Day Gone By appeared in 1990.

In later life, Adams lived in Whitchurch, North Hampshire, a dozen miles from his birthplace. In 2010, he received the first Whitchurch Arts Award for inspiration, given at a pub called Watership Down.